Crowd size forces Louisiana to postpone hearing on proposed ammonia plant

The public hearing for the St. Charles Clean Fuels Plant will be rescheduled after more than 200 people show up in space meant for 60

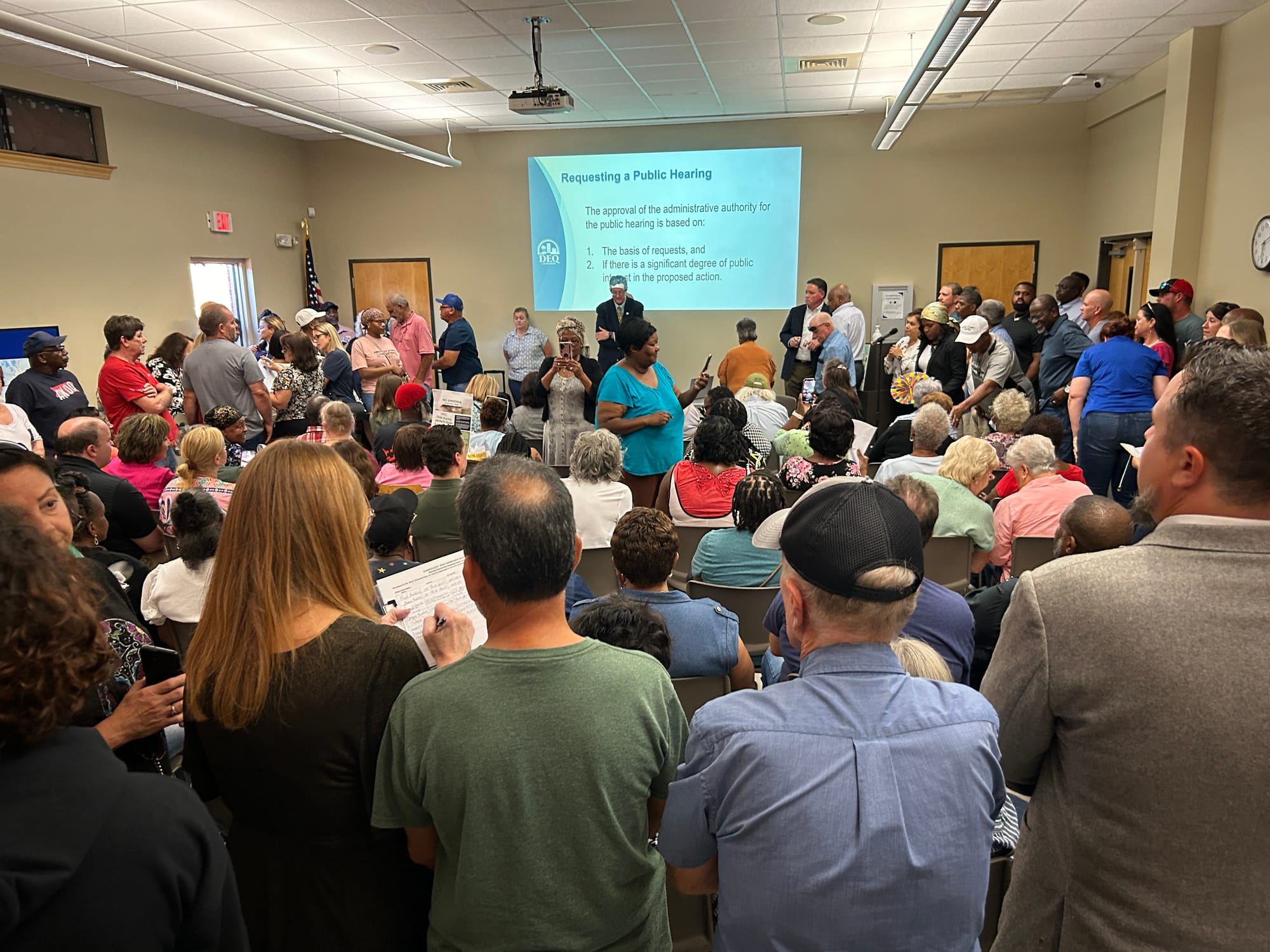

After a crush of about 200 St. Rose, Louisiana, residents showed up to protest a massive proposed ammonia plant Thursday night, a state agency was forced to shut down the meeting because the room could only hold 60.

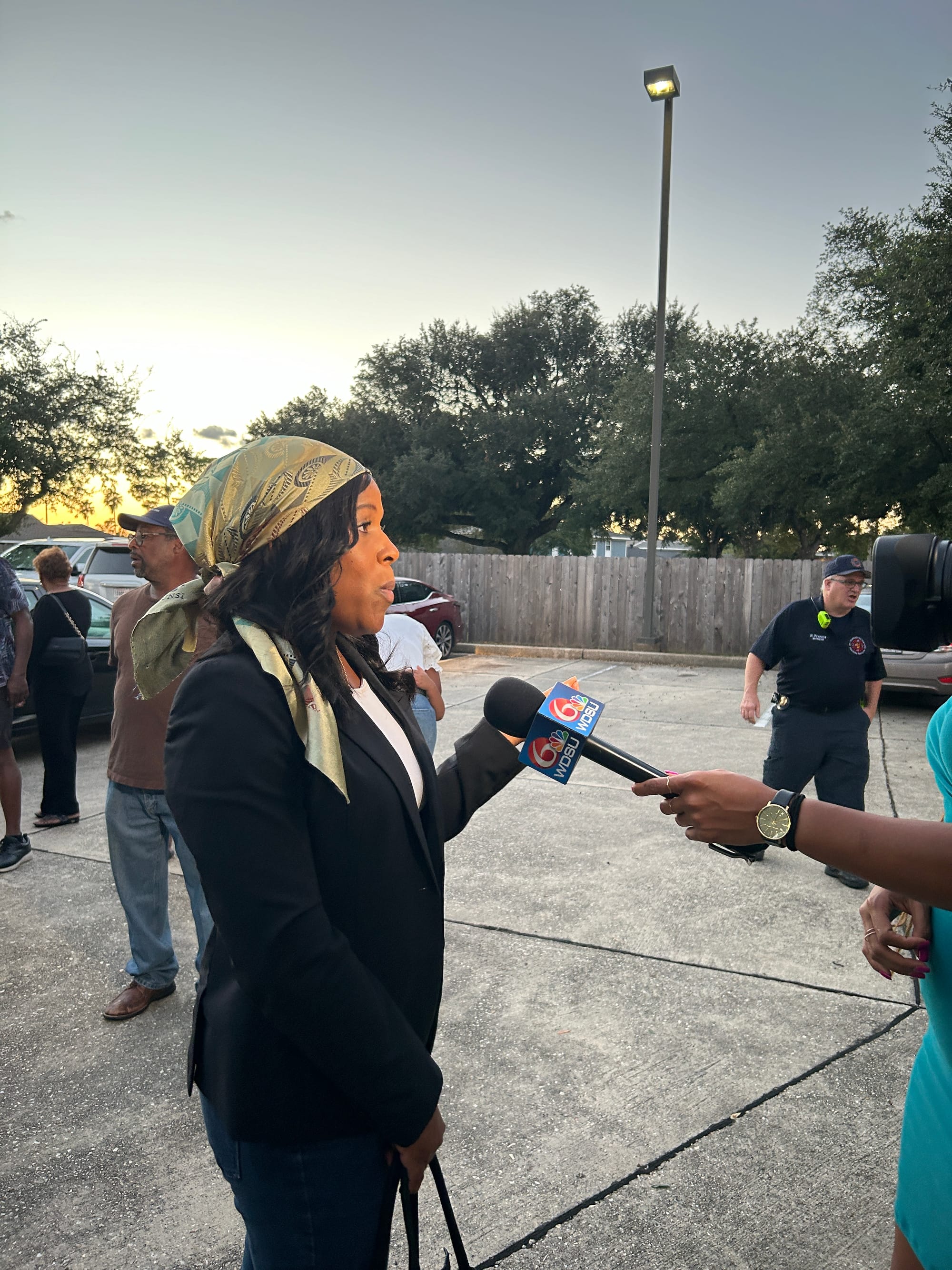

“I am grateful to our residents here in St. Rose that they care enough for themselves and for the future generations to come out,” said Kimbrelle Eugene Kyrereh after the hearing was called off.

Kyrereh founded Refined Community Empowerment to fight the proposed St. Charles Clean Fuels Plant. She said she and others plastered the community around the proposed site with about 2,000 flyers alerting the public to Thursday’s Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality hearing on the facility’s minor source air permit. Last week, Kyrereh emailed DEQ requesting a larger hearing room. The agency did not grant the request.

As residents flowed into the small room at the public library in St. Rose, many said they had just learned about the $4.6 billion plant from the flyers.

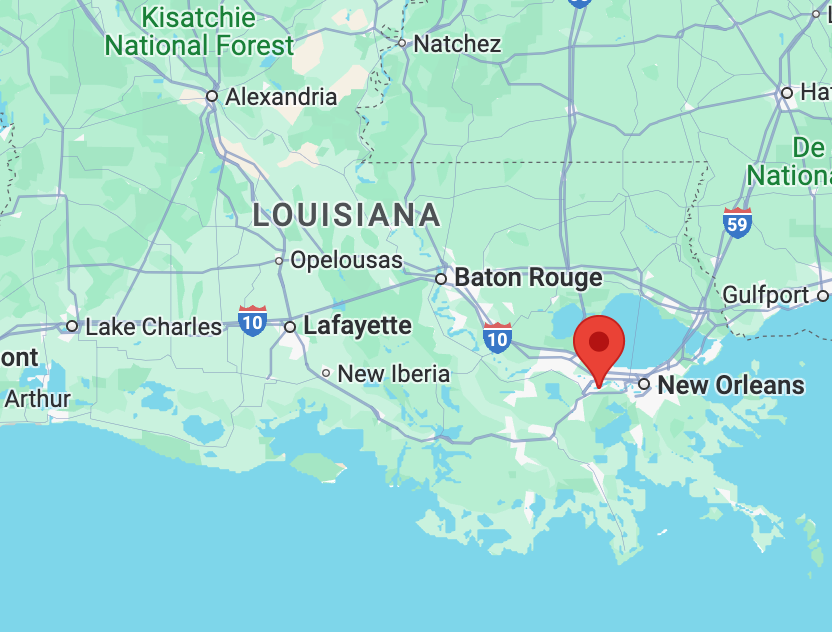

The facility would be adjacent to the International-Matex Tank Terminals site in St. Rose and the historically black community of Elkinsville. The community has been complaining about releases and smells at IMTT for years and are suspicious of the new facility, which plans to store its ammonia at IMTT and use some of that facility’s infrastructure.

“How did we find out … about this? We found out on the streets,” said Rosemary Green, who lives next to IMTT. “How many y'all didn't even know, weren’t aware that this is what's going on? Enough is enough, right?”

In July, the EPA announced a consent agreement with IMTT that included a $23,568 civil penalty for violating the federal Clean Air Act. It also agreed to make $150,000 worth of upgrades “to reduce annual air emissions and unsafe pressure build-up in its storage tanks,” the EPA said. Last week, the company also announced plans to partner with a local nonprofit to provide continuous air monitoring around its facility.

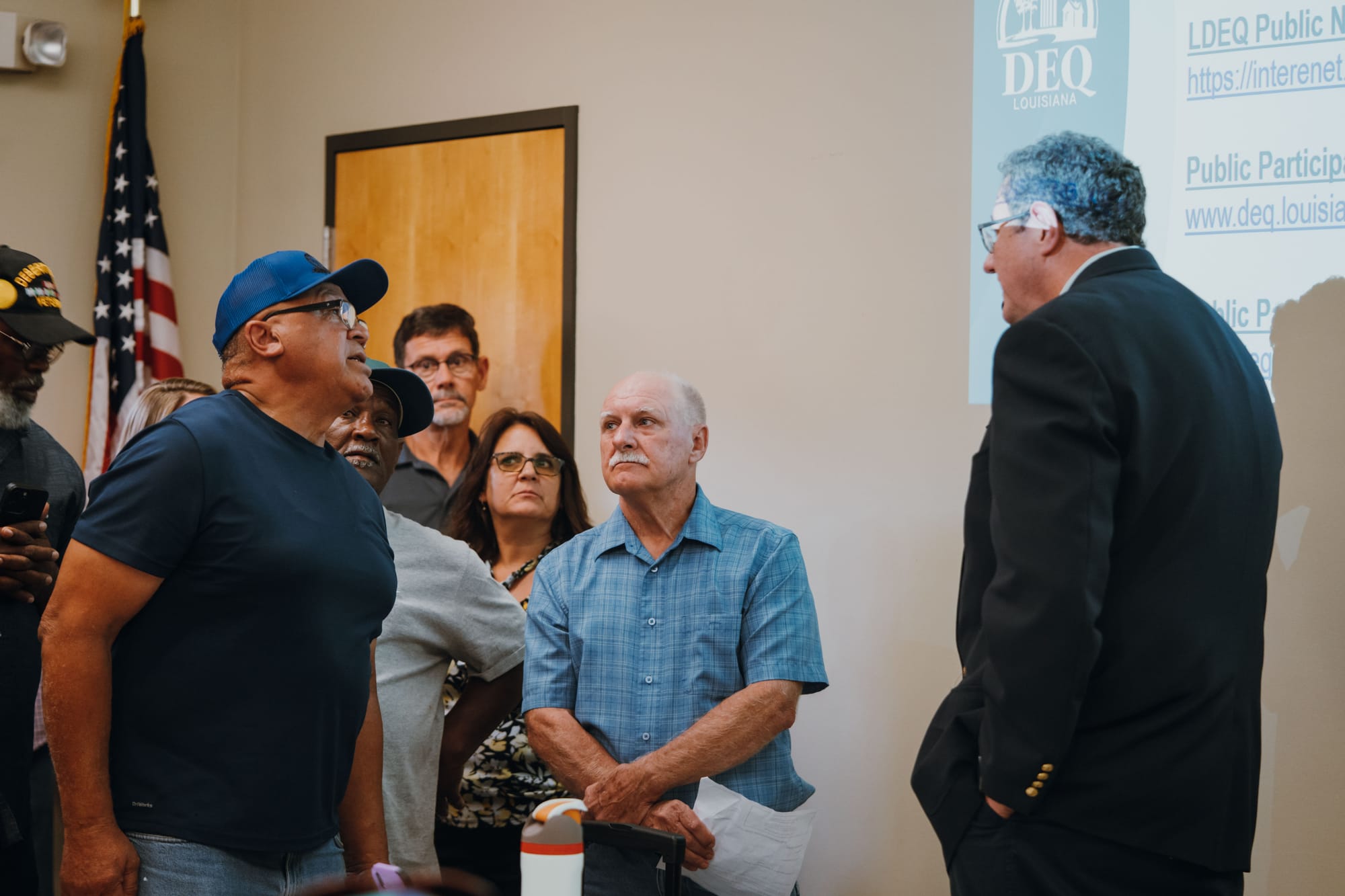

Thirty minutes before the hearing, DEQ started turning people away after the room reached capacity. Those inside repeatedly asked if the meeting could be moved elsewhere, maybe even outside, to accommodate everyone. Eventually all who could fit, at least 150, moved into the room, while others remained outside.

DEQ hearing officer Mike Daniels insisted that because the public notice specified the meeting spot, he could not move it. Someone, however, did call DEQ Secretary Aurelia S. Giacometto, who called back 30 minutes into the hearing and ordered it adjourned. Daniels told the audience that a new hearing would be scheduled at a larger space, and the comment period on the minor source air permit would be extended beyond the Sept. 30 deadline.

As Daniels was talking with Giacometto, St. Rose fire inspector Ronnie Francis showed up and said he would have to shut down the hearing if the majority of people didn’t leave.

Before the meeting ended, three people, including Green, testified in opposition to the plant. One speaker questioned how the amounts of pollutants on the permit could be accurate, a question raised by the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic in its formal response to the permit on behalf of local residents.

“As a major source of ammonia, a toxic air pollutant, and potentially a major source of criteria pollutants, (St. Charles Clean Fuels) will have an enormous impact on the already-overburdened St. Rose community,” the law clinic said. “SCCF has not demonstrated how the benefits of the project will outweigh the costs to human health and the environment … There is no indication in the LDEQ record that the facility adequately considered alternative sites or sufficient mitigation.”

Kim Terrell, director of community engagement at the law clinic, said she’d never seen the state shut down a meeting as it did Thursday.

St. Charles Clean Fuels is a joint venture of global energy investment company Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners and Sustainable Fuels Group. The company’s ammonia would be “clean” because the facility would capture and sequester more than 90% of its carbon dioxide emissions. But the environmental law clinic points out that carbon is not the only pollutant the facility would release.

The facility is one of at least 14 proposed “clean” ammonia projects in the United States announced in the last four years, mostly along the Gulf Coast, spurred in part by credits for carbon capture and storage in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act.

Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.