California calls plastics recycling tech a ‘stunt’; to Louisiana it’s economic development

ExxonMobil wants millions in tax breaks for a Baton Rouge project that would create no jobs, pollute the environment and recycle few plastics

Published by the Louisiana Illuminator

A Louisiana state board is expected on Wednesday approved millions in tax breaks for an ExxonMobil advanced recycling facility in Baton Rouge, that, by the company’s own admission, won’t create any new, permanent, jobs.

The proposed $120 million facility is also unlikely to recycle much plastic, according to a lawsuit brought last month by the California Attorney General. The lawsuit claims ExxonMobil’s development of advanced recycling facilities is a “public relations stunt without any prospect of meaningfully reducing the amounts of plastic waste or virgin plastic ExxonMobil produces.”

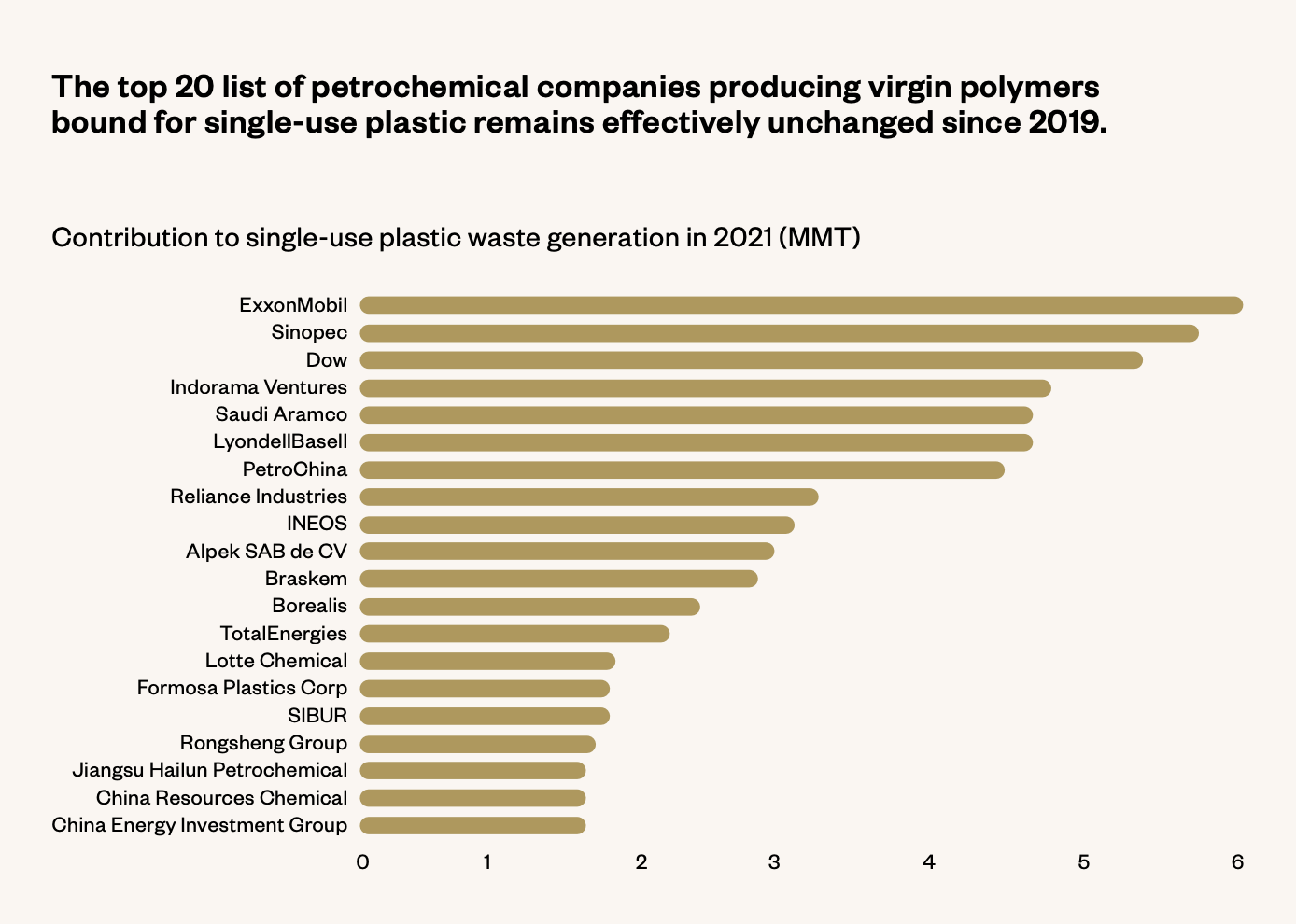

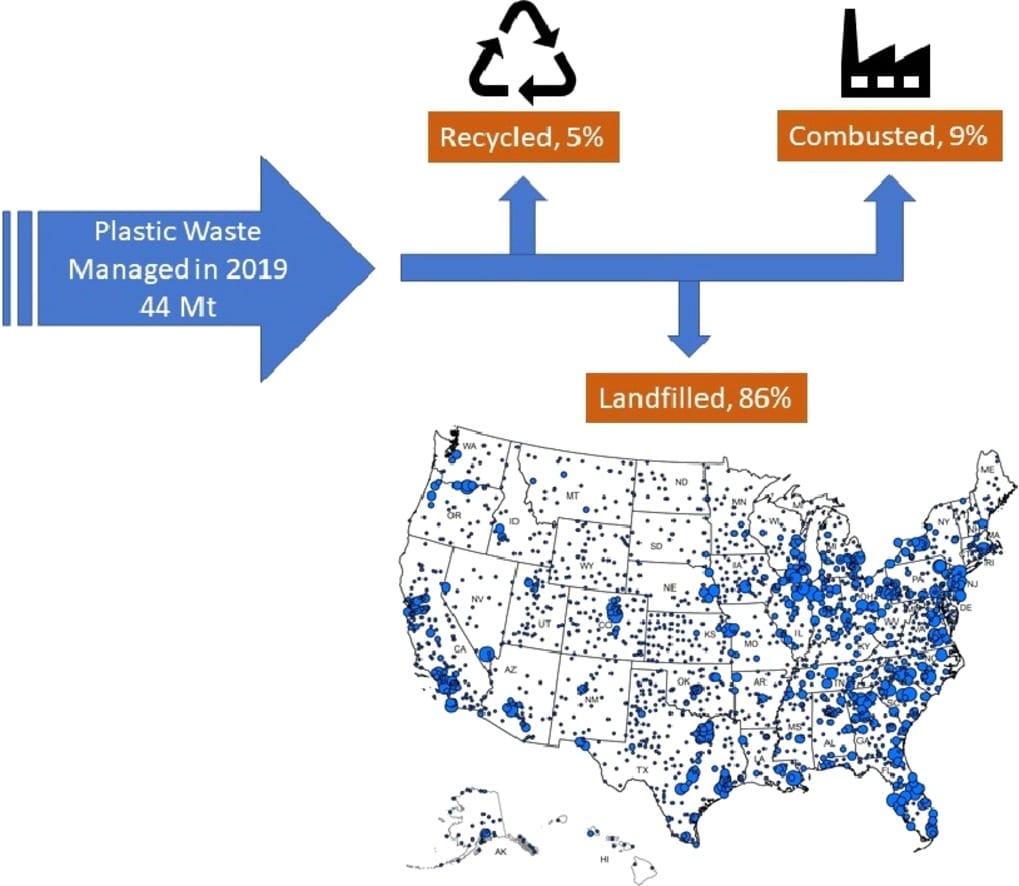

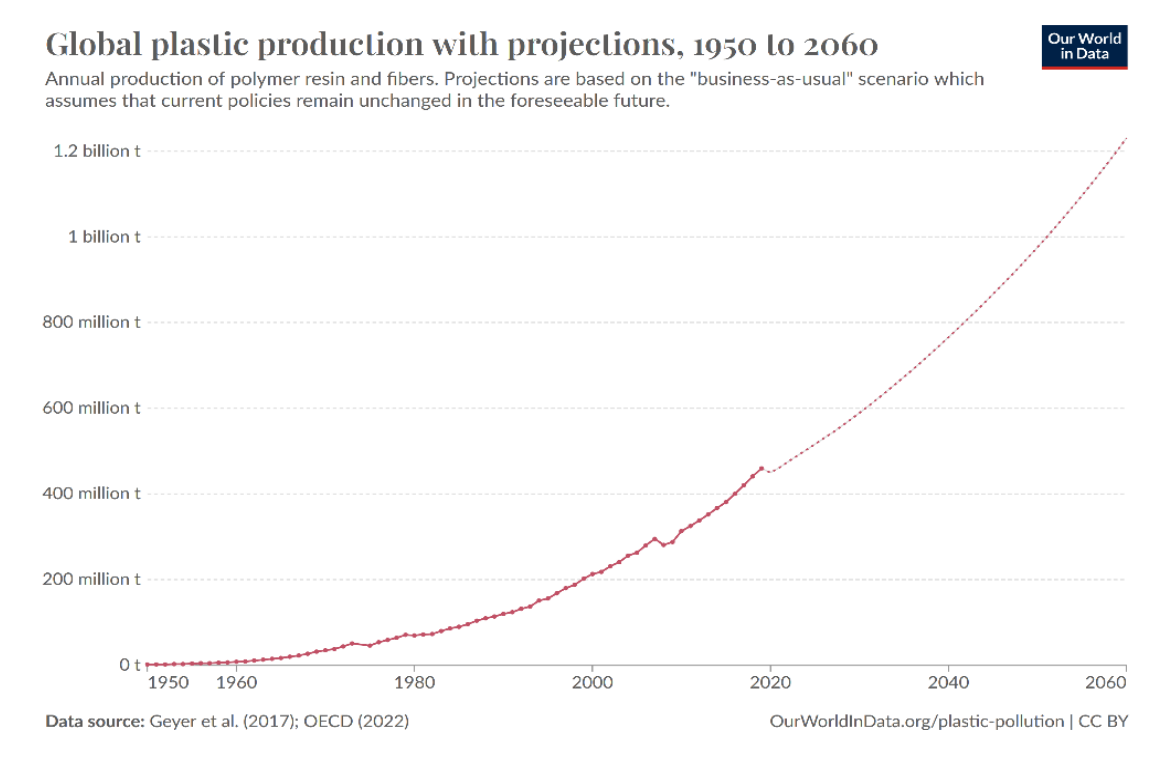

ExxonMobil is the world’s largest producer of the substances used to make single-use plastics. Depending on the year, less than 6% of all U.S. plastics are recycled. The company says advanced recycling will allow more plastic to be recycled.

After ExxonMobil started a pilot advanced recycling facility at its refinery in Baytown, Texas in 2022, it named Baton Rouge as one of seven possible locations around the world for another site. The proposal emerged after Louisiana passed legislation classifying advanced recycling as a manufacturing process rather than solid waste disposal. Twenty-four other states have passed similar legislation.

Yet, almost two years later, the company still hasn’t announced where it will locate its next advanced recycling facility. ExxonMobil is still considering all seven sites, which include Illinois, Singapore and another Texas location, a spokesperson said. The proposal for Baton Rouge is made up of four projects, including plastics recycling and manufacturing isopropyl alcohol to be used in chip manufacturing.

The spokesperson told Floodlight that, to date, the Texas facility has processed 60 million pounds of plastics into “usable raw materials.” By contrast, in 2023, ExxonMobil produced 31.9 billion pounds of plastic, according to the lawsuit.

In August, a joint investigation by Inside Climate News and CBS News found that more than a year and a half after Houston began collecting consumer plastics for the Baytown plant. it has not started processing those plastics. Instead, the mountains of plastic collected from households are creating an increasingly serious fire hazard at a local waste management facility.

The California lawsuit says 92% of the plastics “recycled” by ExxonMobil at its Baytown refinery — which the Baton Rouge facility would be based upon — become fuel. And plastics produced there contain less than 1% recycled plastic.

‘Untold environmental consequences’

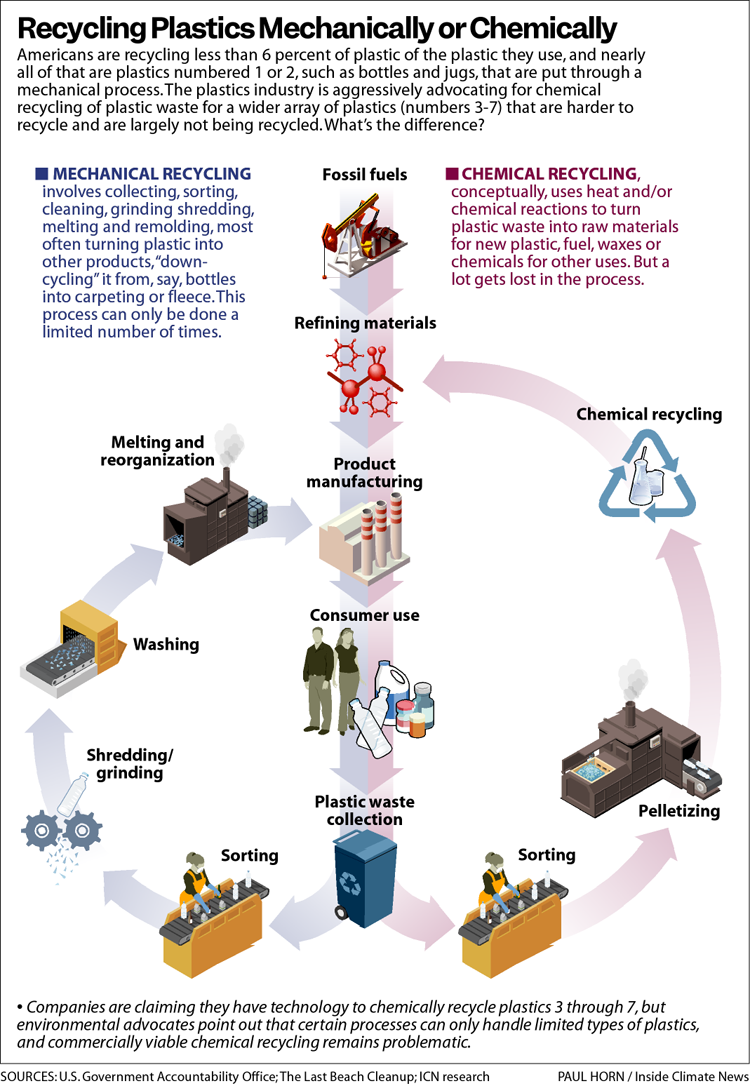

In the 1980s, ExxonMobil began promoting conventional, also called mechanical, recycling to appease public concerns over plastic waste — even though the company knew it was not a solution to the problem, according to the California lawsuit.

The company says advanced recycling through pyrolysis —a process similar to incineration — works better for hard-to-recycle plastics, including chip bags, motor oil bottles and artificial turf. The lawsuit charges the company is not recycling such items, but instead is using clean industrial waste, such as bubble wrap and clear plastic wrap used by businesses, which it primarily turns into fuel.

A 2023 study from the National Renewable Energy Laboratories found that only 1-14% of plastic processed through pyrolysis can be converted back into plastic. The study also says advanced recycling is up to 100 times more expensive and environmentally harmful than producing virgin plastic.

The process also can release toxic substances including benzene, dioxins and other cancer-causing chemicals when the plastics are heated to a high temperature without oxygen.

Questions remain about the impact of advanced plastics recycling on climate change. ExxonMobil says advanced recycling results in fewer greenhouse gas emissions, but the California lawsuit says such claims are “based on the inclusion of inflated and deceptive assumptions.”

The lawsuit cites studies that find putting plastics in landfills releases 20% fewer greenhouse gas emissions than advanced chemical recycling. A study from the Argonne National Laboratory reached the opposite conclusion, finding that advanced recycling — specifically pyrolysis — results in up to 23% fewer greenhouse gas emissions. That study was supported by the American Chemistry Council, of which ExxonMobil is a member.

“It’s a very unregulated process that carries untold environmental consequences — there are other costs that are going to hit East Baton Rouge,” said Erin Hansen, state policy director for Together Louisiana, a grassroots coalition of civic and religious groups.

Another oil giant, Shell, announced earlier this year it was backing away from a promise to turn 1 million tons of plastic waste into oil after it determined it was “unfeasible.” The company had tried out the process at a chemical plant in Louisiana.

Local districts OK tax break

Initially proposed as a $75 million project, the Baton Rouge plant additions were approved for tax breaks of $861,000 for the first year. The tax breaks are typically granted for 10 years.

The approval was granted over arguments the local school district could not afford to give up its share of potential tax revenue, estimated at about $3.6 million. The company warned if the exemption was not approved, it might build the plant elsewhere.

The school board vote came after protests from parents, teachers and students who said the district couldn’t afford to lose its share of the property tax exemption. They argued the district’s teachers and bus drivers are already underpaid.

“If it wasn't in the budget to fund playground equipment, how can it possibly be in the budget to also give one of the most powerful corporations in the world a break, a tax break?” Hayden Crockett, then a 7th grader, asked the East Baton Rouge School Board.

The school board OK’d the tax incentive, with member Patrick Martin arguing the investment and sales tax the ExxonMobil project would bring would provide “substantial benefits to our children, our community and ultimately to our bottom line.”

Exxon doubles its request

Changes in timelines, scope and equipment led the company to cancel that approval, said Mark Lorando of Louisiana Economic Development agency, which administers the tax incentive program. The company filed a new application for a larger $120 million project, requesting a tax break of $1.7 million for the first year — twice as large as its previous request.

The exemption must still be approved by a board of local governments and the governor.

In 2016, Gov. John Bel Edwards, a Democrat, gave local authorities more say in the ITEP decisions and rolled back the incentive from a full exemption of a facility's property tax bill for 10 years to an 80% reduction.

Edwards’ changes were mostly reversed when Republican Gov. Jeff Landry took office earlier this year. While he kept the 80% cap on the exemption — meaning local authorities still collect 20% of the property tax for the project — local authorities come together for one single vote on the project. It won’t receive a separate hearing by the school board.

Any decision the local board makes is not binding, meaning the governor has final say on the application. Landry also eliminated the requirement that a project create jobs.

California, by contrast, is asking ExxonMobil for money.

Attorney General Rob Bonta’s lawsuit asks for an injunction against ExxonMobil using terms including “advanced recycling,” and “chemical recycling,” and is requesting damages from the company, which could amount to billions of dollars.

ExxonMobil said the lawsuit is an attempt to deflect from California's own failures on recycling.

“They failed to act, and now they seek to blame others. Instead of suing us, they could have worked with us to fix the problem and keep plastic out of landfills,” a company spokesperson said in an email to Floodlight. “The first step would be to acknowledge what their counterparts across the U.S. know: advanced recycling works.”

Jane Patton, a U.S. fossil economy campaign manager for the Center for International Environmental Law who lives in Louisiana, says advanced recycling is a “false solution” that amounts to greenwashing and puts an unfair burden on local residents.

“These are communities that are inundated by petrochemical processing and pollution,” she said. “People have to be unbelievably attuned — they literally have to know what the different chemicals smell like so they can know if they can send their children outside. These companies are getting millions of dollars for things that don’t even provide jobs.”

Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.