Black women are leading the fight against polluters in Louisiana — and they’re winning

Philanthropic and government investments in environmental justice are helping nonprofits push back against industrial development

The source of a 2020 report on funding inequity cited in this story has been corrected from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. The report was compiled by Building Equity & Alignment for Environmental Justice.

Louisiana’s Republican governor is opening the door wider to industry. But the voices opposed to the expansion of oil, gas and petrochemicals here — and its impact on vulnerable communities — are stronger than ever.

A collection of local nonprofits and grassroots organizations leading the charge have something in common: They’re led primarily by Black women who are becoming more formidable opponents against industrial expansion in their state. Their strength is fueled, in part, by sizable investments from philanthropies and the Biden Administration, which share their goal to improve environmental justice in the Bayou State.

“We've begged for a seat at the table. We begged for funding. We've begged for national organizations, green organizations, big funders, to listen to us, support us,” said Roishetta Ozane, a Sulphur resident and founder of the Vessel Project of Louisiana. “And we said, if we had the funding and the resources, we could win this thing. We could save our communities.”

Those pleas have finally been heard. Millions of dollars from both private and public sources have poured into Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley” and other communities overburdened by pollution. The federal government has made $600 million available for environmental justice projects through the Inflation Reduction Act, but much of that money from the 2022 spending plan still hasn’t trickled into target communities.

Bloomberg Philanthropies has pledged $85 million for such efforts through its Beyond Petrochemicals campaign, including support for Louisiana-based environmental justice nonprofits Louisiana Bucket Brigade, Hip Hop Caucus and Rise St. James.

The campaign is funded by billionaire and former Democratic New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who also serves as UN Special Envoy on Climate Ambition and Solutions. The campaign says it has halted eight industrial projects nationwide, including three in Louisiana, averting more than 37 million tons of carbon emissions.

Philanthropic organizations also are giving community groups the legal muscle to fight industrial expansion in court. Legal environmental advocacy groups including Earthjustice, the Sierra Club and the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice have been crucial components in advocates’ battles against further development of the oil and gas industry in Louisiana.

And Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry has noticed.

When an international export company abandoned plans to build a massive grain terminal in the state in August, Landry lambasted the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for bowing to “special interest groups” and “wealthy plantation owners” — an oblique reference to local advocates Jo and Joy Banner — who opposed the terminal.

Even before taking office, Landry made moves to stamp out the dissension to industrial development in Cancer Alley.

Earthjustice, a legal environmental advocacy group funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, filed a complaint in January 2022 on behalf of residents in St. John the Baptist Parish, asking the EPA to investigate whether Louisiana regulating agencies had violated Title VI by failing to protect predominantly Black communities from disproportionate pollution and environmental harm.

As attorney general, Landry filed a successful lawsuit in 2023 against the EPA. A judge has now blocked the agency from investigating civil rights complaints tied to environmental pollution in marginalized communities in Louisiana.

Cynthia Sarthou, who retired in 2022 after serving as the executive director for 26 years for environmental advocacy organization Healthy Gulf, said the crusade to stamp out the petrochemical industry in Louisiana could have been further along had philanthropists not taken so long to invest in environmental justice.

But funding around climate change and environmental safeguards only started pouring into the state after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. However, those windfalls of federal and philanthropic aid weren’t consistent and didn’t focus on curbing further industrialization.

“Most of the people who you are seeking money from either made their money through the oil industry or are beholden to the oil industry, or don't want to tick off the oil industry,” Sarthou said.

“Funding has always had to come from the outside,” she added. “People were just convinced that, which is true, the narrative around the oil and gas industry here was too strong. That there was no ability to really fight the industry, and that you just weren't able to win battles.”

Opposition to industrial expansion grows

The pushback against oil and gas in the southeast corner of Louisiana, where predominantly Black communities are surrounded by industrial facilities, has been going on for years. But a few recent wins catapulted this struggle into the national spotlight.

In September 2019, Sharon Lavigne, a special education teacher turned environmental justice advocate, successfully led efforts to stop the construction of a $1.25 billion plastics manufacturing plant in her hometown in St. James Parish. Formosa is in federal court fighting to build the plant, which has been approved by Louisiana environmental officials.

Earlier this year, the Biden Administration announced a temporary pause on liquified natural gas export projects. That pause was lifted in July by a Louisiana federal judge at the urging of Louisiana and other red states. Ozane had led the chorus of opposition to these projects, which, if built, would pump millions of tons of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere and increase worldwide reliance on this climate-killing fossil fuel.

And then last month, the groundswell of dissent built by the Banner sisters, founders of the Descendants Project, contributed to the decision by Greenfield Louisiana LLC to halt its proposed $800 million grain elevator in St. John the Baptist Parish.

For decades, industry has been allowed to thrive and emit dangerous levels of pollution negatively impacting the health and quality of life for Black and brown people. These residents historically lacked the resources to fight back.

But the timing of the recent success aligns with increasing dollars — both federal and philanthropic — that have begun to flow toward environmental justice as donors realize the people closest to the problem are the closest to the solutions.

“What distinguishes grassroots activism from other forms of activism — and what makes grassroots movements effective — is the emphasis on collective action to address an acute problem, often at the local level,” said Ilan Kayatsky, communications director for the Goldman Environmental Prize, which celebrates and supports grassroots activists worldwide.

Lavigne, who founded her faith-based, grassroots environmental organization Rise St. James, was a recipient of the Goldman prize in 2021 for her work mobilizing the opposition against the Formosa plant. And this year, Time Magazine named her one of the 100 most influential people of 2024.

“The surge in awareness of environmental issues can largely be attributed to the influence of grassroots movements,” Kayatsky said. “With the rise of grassroots activism over recent decades, there are more and more organizations — large and small — representing a critical front in the fight against polluting industry and environmental injustice.”

And there’s plenty to fight about.

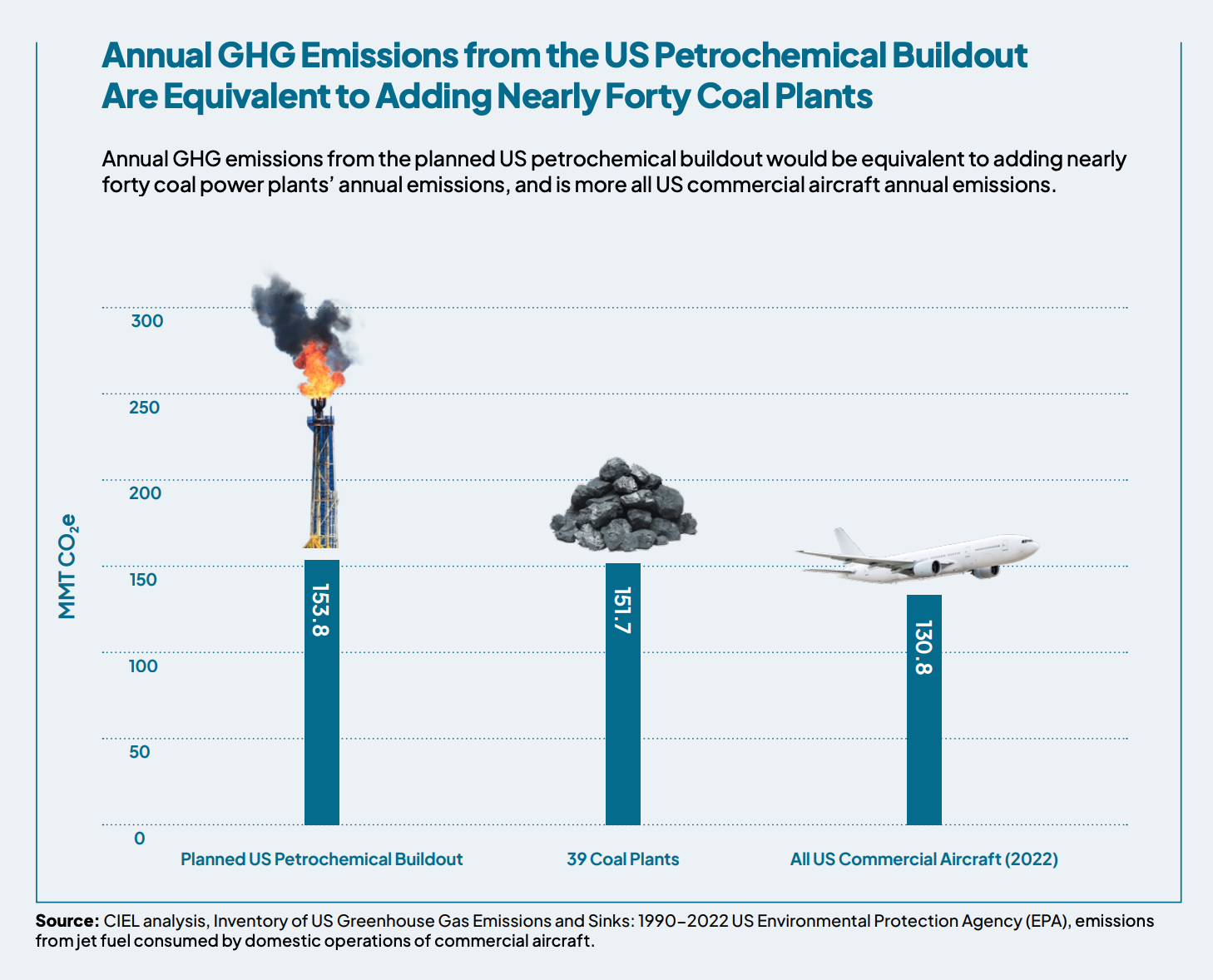

A recent report from the Center for International Environmental Law says the proposed new petrochemical projects in the country, many of which are scattered throughout Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, could increase carbon emissions from the industry by 38% annually — equivalent to nearly 40 coal plants per year.

Disparities noted in minority-led groups

But historically, the funding for environmental justice wasn’t there — especially for groups headed by Black and brown leaders.

In 2020, Building Equity & Alignment for Environmental Justice released a report highlighting the funding disparities between mainstream environmental groups, which are mostly white-led, and environmental justice-focused organizations.

The 12 national foundations the study examined awarded a total of $1.34 billion to environmental organizations and just 1.3% — around $18 million — went to environmental justice groups. And along the Gulf Coast, that trend persisted, with six foundations awarding approximately $12 million between 2016-17 with only about $155,000 allocated toward environmental justice causes.

A separate study released the same year by Echoing Green, a nonprofit that provides seed funding to organizations, found that funders lacked the understanding of the important role of people of color as leaders and in finding solutions to environmental problems.

“Our research found that on average the revenues of the Black-led organizations are 24% smaller than the revenues of their white-led counterparts,” the report said.

‘You need to be investing in these frontline communities’

When Ozane, the single mother of six, started her nonprofit three years ago, she had to use her own money to provide mutual aid and relief after several weather disasters, including hurricanes Laura and Delta, winter storm Uri and the May flood of 2021.

“We don’t tend to get startup money,” Ozane said. “People don't trust Black people. They don't trust Black women. But traditionally and historically when Black people, especially Black women, are supported, we make a difference.”

Conversations around the funding disparities surfaced in 2020 after the death of Geroge Floyd when concern about race and systemic racism reached a crescendo in America.

Roddy Hughes, the southwest Louisiana organizer for the nationwide environmental advocacy organization the Sierra Club, said his group began restructuring its efforts around environmental justice, urging funders to devote more money to minority-led nonprofits.

“My work was built around supporting Roishetta’s work,” Hughes said. “We’ve really pushed donors to do better. Don’t just give to the Sierra Club. You need to be investing in these frontline communities, helping elevate their voices.”

Two years later, in 2022, Bloomberg launched Beyond Petrochemicals, a multi-million-dollar campaign to finance grassroots movements like the Banner sisters’ Descendants Project that are focused on stopping the construction of more than 120 proposed petrochemical projects in Louisiana, Texas and the Ohio River Valley.

“We really seek out those people who have the impact to make change at the highest level, even with, you know, relatively small staff and relatively small budgets,” said Shorey Myers, who leads Bloomberg Philanthropies' petrochemicals initiative. “You have to start with the people who live there and who can testify to the actual impact and have connections to the decision makers who are living across the street from the people who are making the decisions.”

Added Myers: “We couldn't just show up somewhere and knock out a petrochemical facility without incredible leaders in the communities themselves.”

More money, more backlash

With the wins also come new headaches for some.

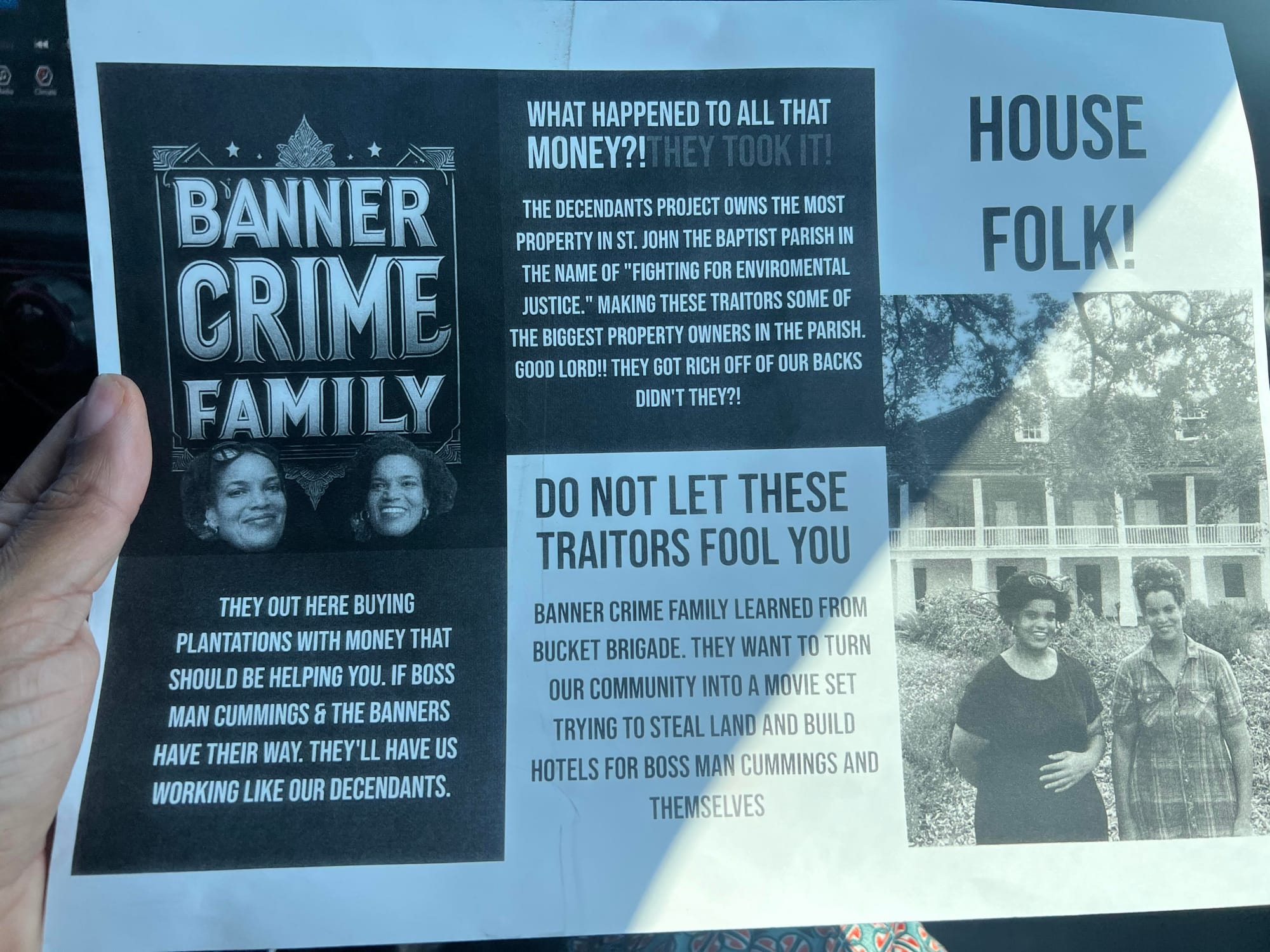

In August, days after the Banner sisters celebrated the news that Greenfield Louisiana LLC was halting plans to build the massive grain elevator in their parish, flyers started popping up in their hometown accusing them of being criminals. The flyers claimed the Banners used the grant funding they were receiving to buy and restore plantations to boost tourism — not help the community.

Joy Banner said the flyers were just the latest in a series of attacks against them as they fought to stop the grain elevator. She pointed to a Facebook group that disseminated disinformation about them and their organization.

Although the Banner sisters did speak with local law enforcement about the harassment, it never progressed to arrests or formal complaints, she said.

“When these companies come into our community, what they do is they get people from the local community on board to start influencing other people to start sowing the seeds of division and relationships break as a result of it,” Banner said. “As Black women, when we fight back, we are not expected to win. We are not expected to be seen as leaders.”

The press representative for Greenfield Louisiana LLC did not respond to a request for comment.

It’s more than the environment

Joy Banner said minority-led nonprofits in Louisiana are doing a lot more than just standing up against environmental racism. Their nonprofit was originally founded to honor, preserve and celebrate the history of the community of Black enslaved people in the river parishes. That effort eventually intersected with environmental justice due to the oil and gas industry’s push toward more industrialization there.

Through necessity, many of the nonprofits growing in Cancer Alley and other marginalized communities have taken on many tasks, including hurricane preparation and cleanup, food distribution, vaccinations and public health issues.

“All the little ways in which our governments are failing us we’re becoming our own little micro governments,” Banner said.

Erin Rogers is with the Hive Fund for Climate and Gender Justice, which specializes in raising funds and awarding grants to nonprofits led by minority women in the communities hardest hit by pollution and climate change.

“Some of the most effective and powerful and visionary leaders doing organizing and advocacy in those communities are women of color and sadly, philanthropy undervalues their contributions because of just our own systemic bias within philanthropy,” Rogers said.

She added that the work Lavigne, Ozane and the Banner sisters have accomplished “breaks this psychological grip that I think a lot of these polluting industries have on us in general, but especially these communities where it really crushed any hope that anything will ever change.”

What happens if the money stops?

It’s something Sarthou says could happen given how “fickle” the philanthropic sector can be.

“This is the truth: They want big successes in a short period of time. It's how they define success,” she said. “(Are) they going to decide in two more years that there have been wins, but there hasn't been this mega shift, so they're going to just move their money somewhere else?”

Note: Bloomberg’s Beyond Petrochemicals supports Floodlight. Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action. Read more about our editorial independence standards.