Federal gas export study not the final word on US LNG projects

A new analysis shows super-chilled methane harms the climate — but falls short of recommending a halt to the booming industry

Published by the Louisiana Illuminator

A green light doesn’t necessarily mean go for the 18 liquefied natural gas export projects that have been in limbo pending a U.S. Department of Energy study on whether LNG exports are in the public interest. Additional permits, court fights and market forces will impact whether the proposed increase in LNG capacity in the United States will be built, according to experts.

On Tuesday, DOE released the long-awaited study, which found that a single LNG project, exporting 4 billion cubic feet of gas a day, would emit more annual greenhouse gas emissions than 141 of the world’s countries each did in 2023.

The study also validated concerns of residents who live near existing LNG facilities, finding that LNG production and transportation adds more pollution to areas already burdened by other petrochemical industries.

“LNG exports not only devastate our environment but also escalate our energy costs and compromise our futures,” Roishetta Ozane, founder and CEO of the Vessel Project of Louisiana and a consistent opponent of the LNG buildout, said in a written statement. Ozane and others urged the Biden administration to take more action on the issue before the president leaves office next month.

If no limits are placed on U.S. LNG exports, the study finds such “unconstrained” development would increase energy prices by $100 or more per year for every household in the United States. Industrial sectors, which rely on natural gas, would see costs increase $125 billion through 2050, leading to potential price hikes for consumer goods.

“The more volumes of U.S. LNG are exported, the greater the risk of this global price volatility being imported into our domestic market and impacting U.S. consumers and manufacturers,” Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm wrote in a statement accompanying the report.

However the analysis, ordered by the Biden administration in January, does not say that LNG exports should be stopped.

Granholm points out that because of a 60-day comment period, decisions on future exports will be made by the incoming administration. But the facts laid out in the study could slow or stall President-elect Donald Trump’s intention to increase production, one long-time energy observer said.

“We think that this updated public interest analysis is going to make it much harder for Trump to try and quickly approve these pending applications, because we've got a factual record by the agency that is being developed that Trump is going to have to counter,” Tyson Slocum, director of Public Citizen’s energy program, said in Dec. 11 press conference before the study’s release. “He's going to have to come up with his own studies, and that's going to take some time.”

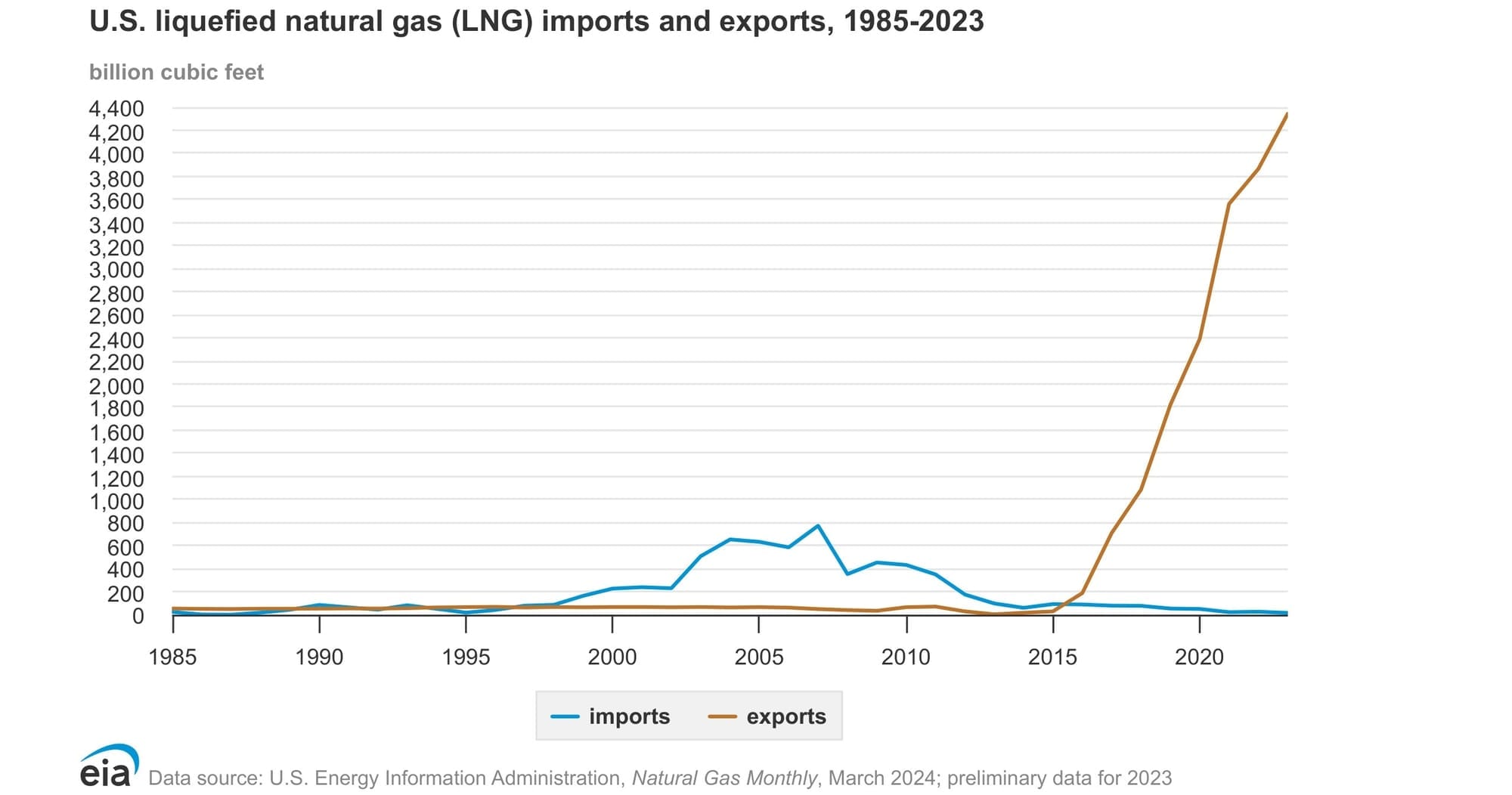

The United States is the world’s leading exporter of the super-chilled methane gas.

The methane industry and its political allies say LNG will help transition the world off dirtier, more carbon-intensive fuels. But the study concluded the most likely scenario is that “additional U.S. LNG exports displace more renewables than coal globally.”

Massive pipeline of projects

At the end of 2023, the United States was exporting 14 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d) to more than 30 countries, including in Europe, which sought to replace natural gas piped from Russia following the start of its war with Ukraine.

By the time permitting was paused earlier this year, the United States had already OK’d construction of an additional 48 bcf/d of LNG — including Venture Global’s Plaquemines LNG in Louisiana, which started production on Dec. 14.

The DOE study and resulting pause placed 18 projects, capable of producing an additional 24 billion cubic feet per day, on hold. Several of those projects, including Commonwealth LNG and Venture Global’s CP2 project in Cameron Parish, still need approval from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) before DOE can approve export authorization.

FERC rescinded its approval of the largest of those projects, CP2, pending additional environmental analysis on the terminal’s potential air pollution. Venture Global has said it will complete those studies and expects FERC’s approval in July.

But even FERC and DOE approval doesn’t mean a project will move forward. Projects totaling 22 billion cubic feet per day have been approved but not yet reached a final decision on moving forward. Companies need to line up enough long-term contracts to start construction, typically 75-80% of their capacity. Then, building the facilities can take three to five years.

“Ending of the pause in the short- and medium term (four to five years) won’t do anything to the global gas/LNG market,” said Anne-Sopie Corbeau, a researcher at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

Looking forward, it’s unclear whether there will be a demand for more LNG, Corbeau said, citing a recent analysis from the International Energy Agency.

“On the one side, you have analysis like the IEA showing that LNG export capacity existing and under construction is sufficient to meet any LNG demand by 2030 and even up to 2040,” she wrote in an emailed response to Floodlight.

But Corbeau cited other work by Shell and WoodMackenzie that disagree, concluding “that there is a lot of demand to absorb the LNG.”

Corbeau also cautions that other countries, for their own global security, might want to diversify where they get their LNG. If the projects pending DOE approval move forward, the United States would control 40% of the world’s LNG.

Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.