Like carbon dioxide, this Louisiana task force’s work is deep underground

A report due in February still hasn’t been submitted after a series of public meetings; leaders of the carbon capture and sequestration study are mum

Published by the Louisiana Illuminator, WWNO, WKRF, Yahoo! News

A special legislative task force assigned with exploring the impacts of carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) in Louisiana still hasn’t submitted a report of its findings — five months after it was due. And its chairman and the lawmaker who created the group won’t say why.

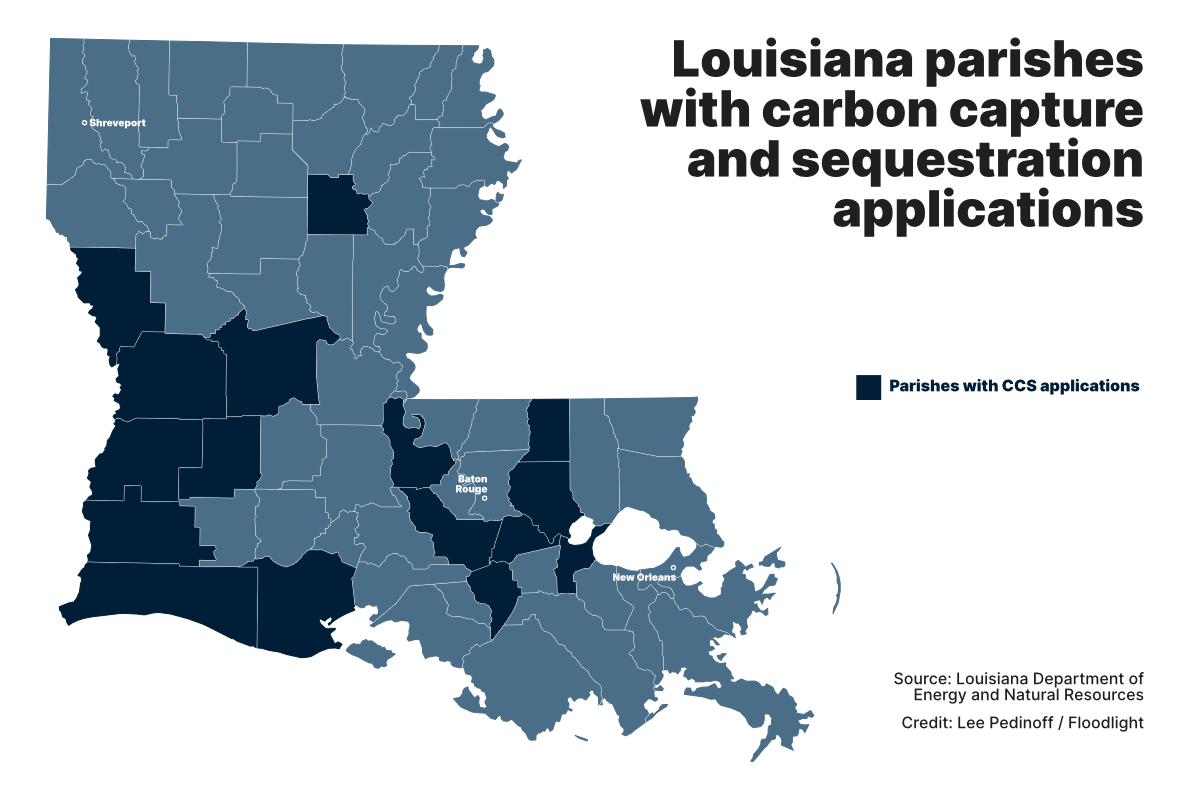

Louisiana is ground zero for CCS, with more than two dozen projects aiming to remove industrially produced carbon dioxide and storing it permanently underground to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

More than $20 billion in private investment in CCS has been planned, according to the state’s economic development agency. Louisiana Economic Development says the state’s 50,000 miles of pipelines, its deep layers of shale, clay and sand and minimal seismic activity make Louisiana a good location for CCS.

But since the inauguration in January of GOP Gov. Jeff Landry, the task force — like the technology it was directed to explore — appears to be deep underground. And questions remain about the safety and effectiveness of CCS, which is a cornerstone of U.S. efforts to combat climate change.

There is no indication if or when the task force will submit its findings to the Senate Committee on Natural Resources after holding a series of meetings in late 2023 and in January before Landry took office. In the meantime, the applications for several projects are moving through Louisiana’s permitting process.

Jackson Voss, the climate policy coordinator for the Alliance for Affordable Energy, says the unknown status of the task force’s report is emblematic of how the state government and industry have opened Louisiana up to the controversial technology without proper scrutiny.

“Even during the hearings of this task force, it became clear that the true aim here was dismissing or discrediting people’s concerns, not seeking to address them,” Voss said.

Concerns around carbon capture include the potential for earthquakes, groundwater contamination and CO2 leaking back into the atmosphere through abandoned and unplugged oil and gas wells or pipeline breaches. Major carbon dioxide leaks have forced people to evacuate their homes in recent years, including an episode April 3 in Sulphur, Louisiana, which released an estimated 107,000 gallons of gas. Carbon dioxide can cause drowsiness, suffocation and even death.

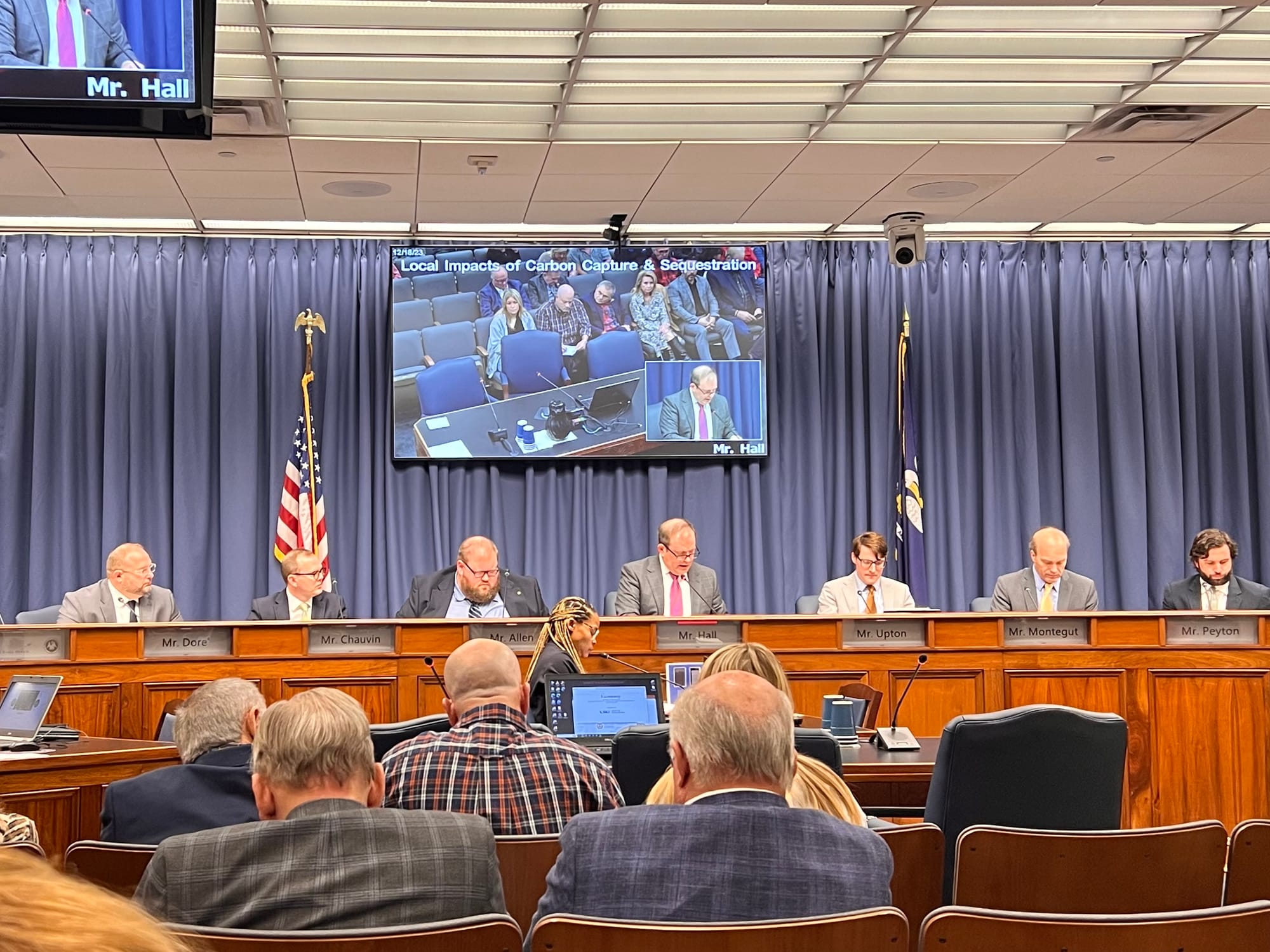

The secretary for the Louisiana Senate confirmed last week that the Task Force on the Local Impacts of Carbon Capture and Sequestration still hadn’t submitted the report it was mandated to complete by Feb. 15 — as outlined in the bill authored by Republican Sen. Heather Cloud of Turkey Creek.

Cloud did not respond to multiple requests for comment about the status of the task force and its report. Keith Hall, the task force’s chairman and director of Louisiana State University’s Energy Law Center, also failed to respond to multiple attempts by Floodlight to reach him for comment.

The task force held four public meetings, hearing from residents near proposed CCS projects as well as state and local leaders, academics and industry officials.

Opposition to carbon capture mostly came from residents and local leaders who didn’t trust the technology not to have serious environmental or health impacts while most in the industry framed it as the most promising way to meet the Biden Administration’s 2050 net-zero emission goals. They also touted the potential in job growth and increased revenue for the oil and gas industry.

The task force’s report was supposed to be a prelude to this year’s legislative session, which ended in June. State lawmakers passed five bills enacted into law related to carbon capture — which included allowing the use of eminent domain authority for pipelines and wells and providing liability protections for landowners who lease their property for CCS projects. Landry vetoed a sixth bill that would have sent 30% of all revenue received by the state for projects built on state land to parishes where the facilities operate.

Louisiana is one of three states which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency granted primacy status, meaning it has the authority to approve injection wells utilized for CCS. That decision is currently being challenged in federal court by three environmental groups, including the Alliance for Affordable Energy.

They’re pushing the courts to reverse EPA’s decision, asserting that the federal agency’s actions violated the Safe Drinking Water Act and other federal statutes. The lawsuit argues Louisiana regulations are less stringent than the EPA’s and that the federal agency failed to show the state had the staff and expertise to implement the program.

Since the EPA gave the state primacy, the Louisiana Department of Energy and Natural Resources has been reviewing applications for 26 CCS projects, mostly in southern Louisiana.

As of July 15, DENR had not approved any injection well permits for CCS. At least nine applications are in the final stage of the technical review process.

Agency spokesman Patrick Courreges said after state geologists and engineers are done scrutinizing the projects’ construction plans and modeling data, public hearings will be held before any final decisions on permit applications.

Voss said the task force was likely a perfunctory move by state lawmakers wanting to claim they’ve done due diligence when it comes to the technology.

“(The task force) seems to have not even done what was required of it — which was producing a report recommending ways that the Legislature could address the potential negative impacts of CCS on communities,” he said.