$80 million, few rules: Louisiana’s energy efficiency ‘slush fund’

One of the least energy efficient states allows elected commissioners to use ratepayer money for ‘patronage’ projects — with little oversight

Published by the Louisiana Illuminator, WWNO, Renewable Energy World

When a lighting contractor approached the Iberia Parish School District in Louisiana and offered it no-strings attached money for energy efficiency upgrades, Harry Lopez, manager of maintenance for the district said, “Flags went up, of course.”

Lopez had a reason to be cautious. Advocates and contractors alike say there isn’t a single program in the country that offers free money for efficiency upgrades to schools or other public buildings — except in Louisiana.

After learning the too-good-to-be-true offer was real, Lopez signed up. To date, contractors have installed energy-saving LED lights in more than a dozen schools in the Iberia Parish district at a cost of $2 million, paid for by Louisiana’s residential and commercial electric customers through their monthly power bills.

The free money came from the Louisiana Public Service Commission’s “public entities” program run by each of the five commission members within their respective districts.

The program is funded by half of the money collected from the monthly energy efficiency fee charged to ratepayers of the state’s largest utilities. The other half is used by the utilities for their own energy efficiency programs.

Each of the elected commissioners receives $2.2 million to $3.8 million per year to allocate to schools, municipalities, parks and other public entities in their districts for energy efficiency projects. Since the program began in 2017, the commissioners have awarded about $80 million, mostly on lighting and some for upgrades to heating and cooling systems.

The commissioners’ program is intended to cost-effectively reduce energy consumption — a strategy that can lower utility bills and benefit the planet through reduced fossil fuel emissions. In many cases, it accomplishes those goals.

But with few rules, almost no competitive bidding, an opaque selection process and no independent audits, it is also a wasteful “patronage” system, according to one energy watchdog.

Even some commissioners question the lack of safeguards around the program. But largely they praise it, saying it benefits everyone in the state by lowering power bills for government facilities.

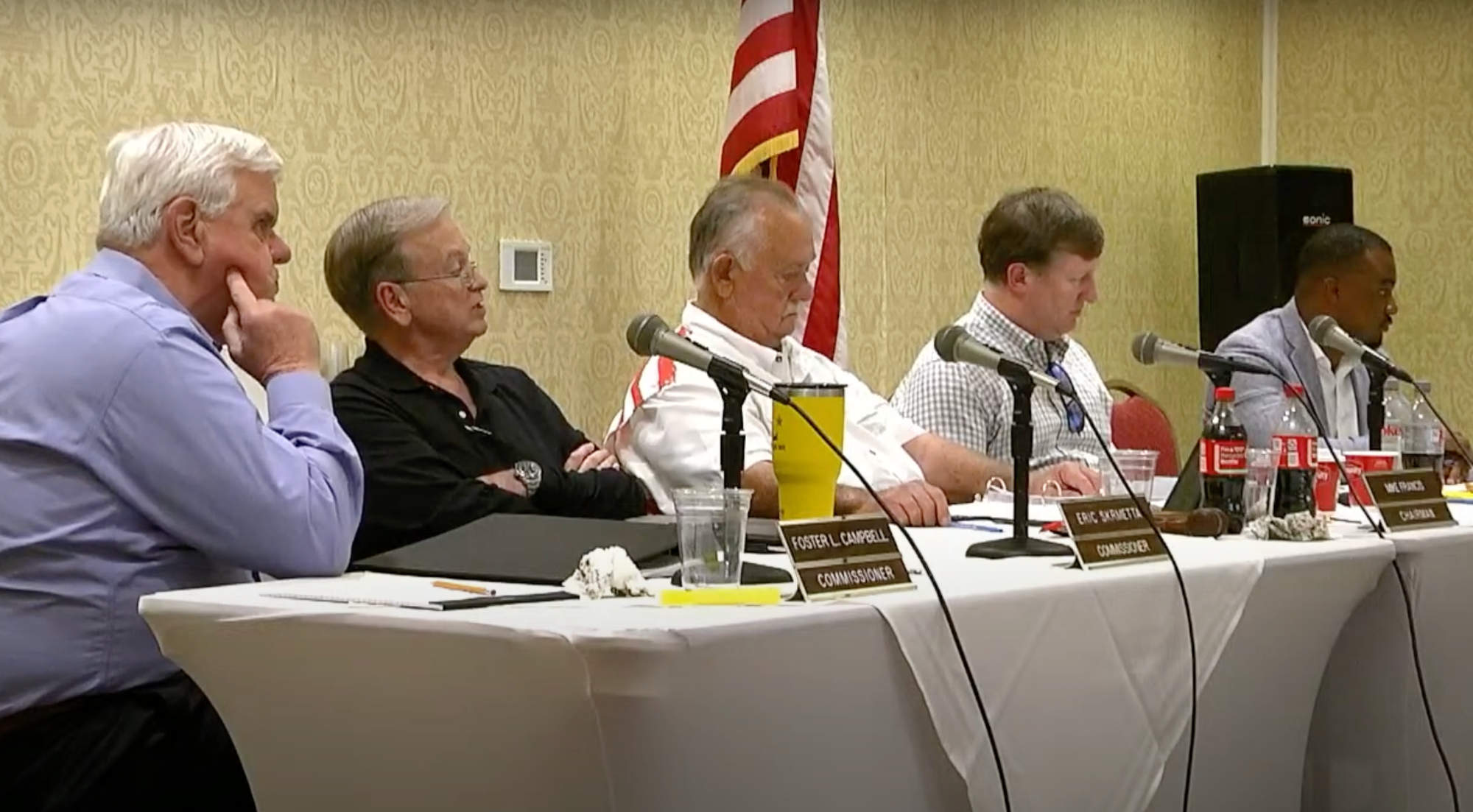

“The concept that it's improper or corrupt, or any other adjective you want to assign to the public entity program, I think is just incorrect,“ Republican Commissioner Eric Skrmetta said.

Democratic Commissioner Davante Lewis has a different view, calling the program, “literally … a slush fund with no checks and balances on commissioners to dole out cash that is collected from every ratepayer.”

Commission kills plan for independent program

In April, the commission on a 3-2 partisan vote killed a long-debated statewide energy efficiency program to be run by an independent third party after Republican commissioners argued the administrative cost for that program was too high.

Some commissioners boast their program only costs 1-2% of its budget to administer. But Lewis and his staff found the true administrative costs paid to contractors are between 30% and 35%.

An analysis conducted by a commission consultant and shared by Lewis shows that by one metric, the commission’s program was nearly twice as expensive as the program commissioners rejected. That analysis said the commissioners’ program costs nearly 5 cents per kilowatt hour (kWh) of energy saved, compared to the proposed third-party program, which would have cost 2.8 cents per kWh saved.

Daniel Tait, a researcher with the watchdog Energy and Policy Institute who has investigated Louisiana’s public entities program, pointed to what he sees as hypocrisy in rejecting the independently administered program.

“(The commissioners) want to yell about how energy efficiency is not a good investment,” Tait said. “Then they go over here to this public entities program, and they are wasting dollars left and right on ineffective energy efficiency programs.”

Consumer advocate Logan Atkinson Burke says the commissioners’ program does not directly help the people who need it the most in one of the nation’s poorest states. Louisiana residents use the most electricity per household in the United States. Upwards of one in five households in some parts of Louisiana can’t afford their monthly power bills.

At the same time, industries, which use almost half of Louisiana’s electricity, can opt out of paying for it.

“I don't think it's appropriate,” Burke said, “for there to be such an opportunity for, quite frankly, patronage … to have zero-cost programs that low-income customers are paying for.”

Documentation missing, rules ignored

The energy efficiency programs run by Entergy Louisiana, Cleco and Southwestern Electric Power are guided by more than 12 pages of PSC rules requiring evaluation, verification and proof of cost effectiveness. The utilities must file hundreds of pages of documentation about their energy efficiency programs each year. Entergy Louisiana’s 2024 report was 520 pages.

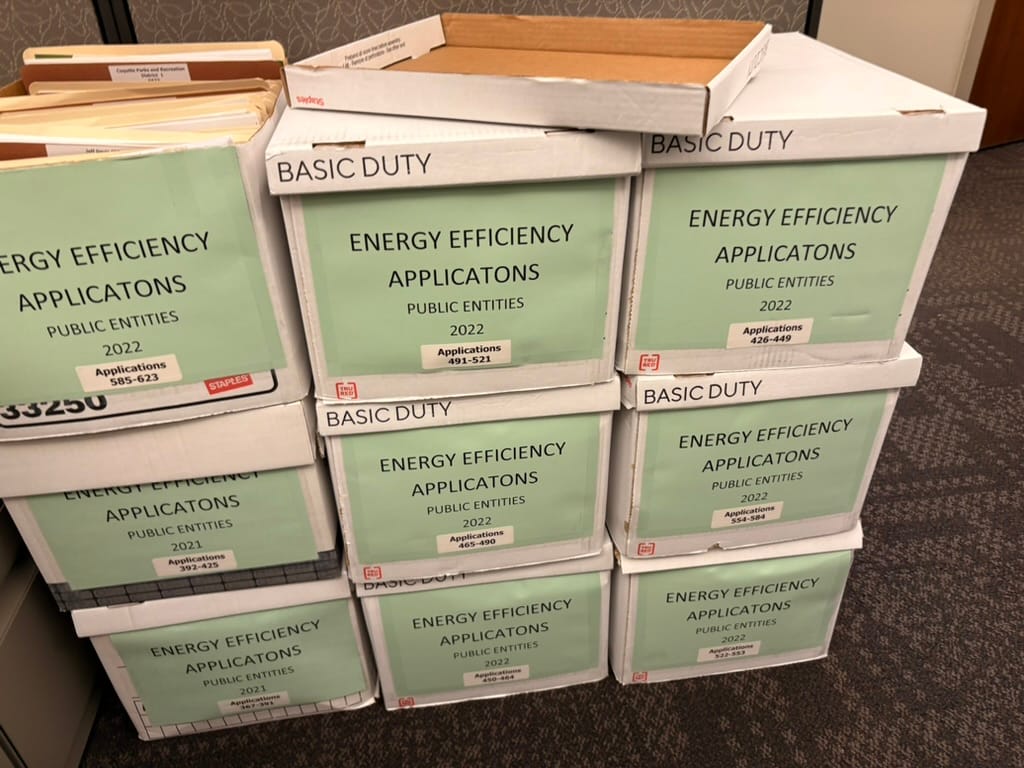

By contrast, the commissioners’ program requires a fraction of that documentation. The rules run just three pages. And record-keeping is scattershot; even the total amount spent on the program isn’t clear on an internal commission spreadsheet that loosely tracks the projects.

The few rules the commission has for its own program are not always followed. Floodlight could not locate any annual reports filed by any of the recipients, even though the eight-year-old program requires annual reports for three years after a project is finished.

The PSC also could not find those records. Agency spokesperson Colby Cook said the agency would “circle back with recipients where the project has been completed to ensure they are in compliance with the reporting requirement.”

The rules require a project “must demonstrate an improvement in energy efficiency.” But Lewis described the selection process as “undefined.”

The applications are taken, evaluated, approved, and upon completion, inspected, almost entirely by the commissioners and their staff, though the commissioners began hiring part-time engineers in each district to help evaluate the applications in 2021.

“This is an area of detail that is challenging and unlikely that commissioners or their staff would have the expertise in,” said Forest Bradley-Wright, state and national utility director for the nonprofit American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy.

Not ‘designed for cost savings’

It’s difficult to tell whether the prices charged under the commissioner-led program are fair.

The invoices and projects are hard to compare, said Mike Morris, owner of MM Energy Solutions, the largest contractor with the public entities program. Even in the one district where a commissioner requires three bids on every project, those bids might be for completely different projects.

Contractors don’t respond to a request for proposals (RFP) for the projects — which is standard in government contracting — but instead submit proposals they devise on their own. One might propose new tube lights, Morris said, while another flat panel lights, which can be more expensive but provide better lighting.

“There's no way to compare it, because there's no RFP with specifics on what you are actually bidding on,” he said. “It’s really hard to put an exact apple-to-apple on all this.”

In addition, Floodlight found that some of the projects approved by the commissioners won’t last long enough to pay for themselves.

According to the PSC’s own records, it would take an estimated 249 years’ worth of energy savings at $600 a year to pay off the $124,000 cost of new lights on a softball field in Ascension Parish, south of Baton Rouge. And in 128 years, energy savings from lighting upgrades around Jefferson Parish would finally pay for the $650,000 cost of those lights.

Floodlight found one-fifth of the commission’s projects will take more than 10 years to pay off — a common benchmark to determine if a project is worth the investment.

Commissioners acknowledge replacing infrequently used lights, such as those at ballfields, is not the most effective for energy efficiency but that those projects benefit entire communities.

The commissioners’ program “has not been designed for cost savings,” Burke said.

“It has been designed to be an opportunity for … five elected officials to dole out money to the political entity of their choice.”

Program emerges ’out of the blue’

Harry Lopez in Iberia Parish isn’t the only one unfamiliar with the PSC’s public entities program. When Louisiana’s utility-run program came up for reauthorization in 2017, then-Commissioner Lambert Boissiere, a Democrat, introduced a never-publicly-discussed proposal to establish a commission-run energy efficiency program. It passed unanimously.

Bradley-Wright, who then worked at the Alliance for Affordable Energy, said the establishment of a new efficiency program was a complete surprise.

“To my knowledge it had never come up before and did indeed come out of the blue,” Bradley-Wright said.

Floodlight found that Boissiere, who led the charge for the program, didn’t use any of that money for energy efficiency projects in his district for four years — until 2021. Longtime incumbent Boissiere was defeated in 2022 by Lewis, who inherited $16 million in unspent energy efficiency funds.

Boissiere acknowledges the program has flaws.

“I felt that, in my opinion, it could have been administered in a more transparent manner,” he said. “It would make the policy that much better. I just always fought to make it a little better.”

Morris says many of the schools he’s worked at are long overdue for a lighting upgrade. He says some of the lighting hadn’t been changed since he went to middle school in Opelousas. Morris is 70.

“You ought to talk to these people in these schools,” Republican Commission Chairman Mike Francis said. “They're flipping out man, with their cost savings and the new lights. They're even complaining they're too bright.”

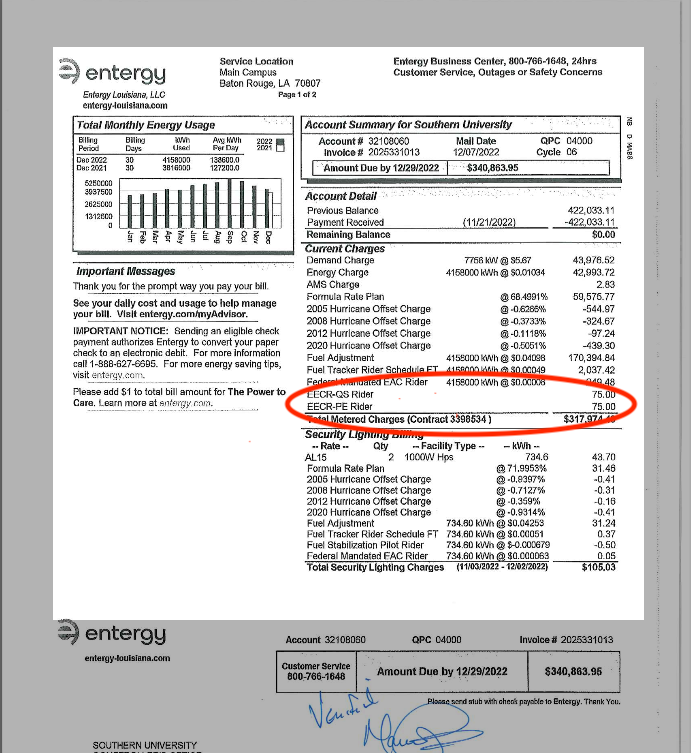

Even Lewis, who has concerns about the program, isn’t shy about promoting its outcomes. Last year, he posted a photo of himself on Instagram with a $1.46 million check with officials from Southern University, which received more than $4 million from Lewis for energy-efficiency projects.

‘Free enterprise’ at work?

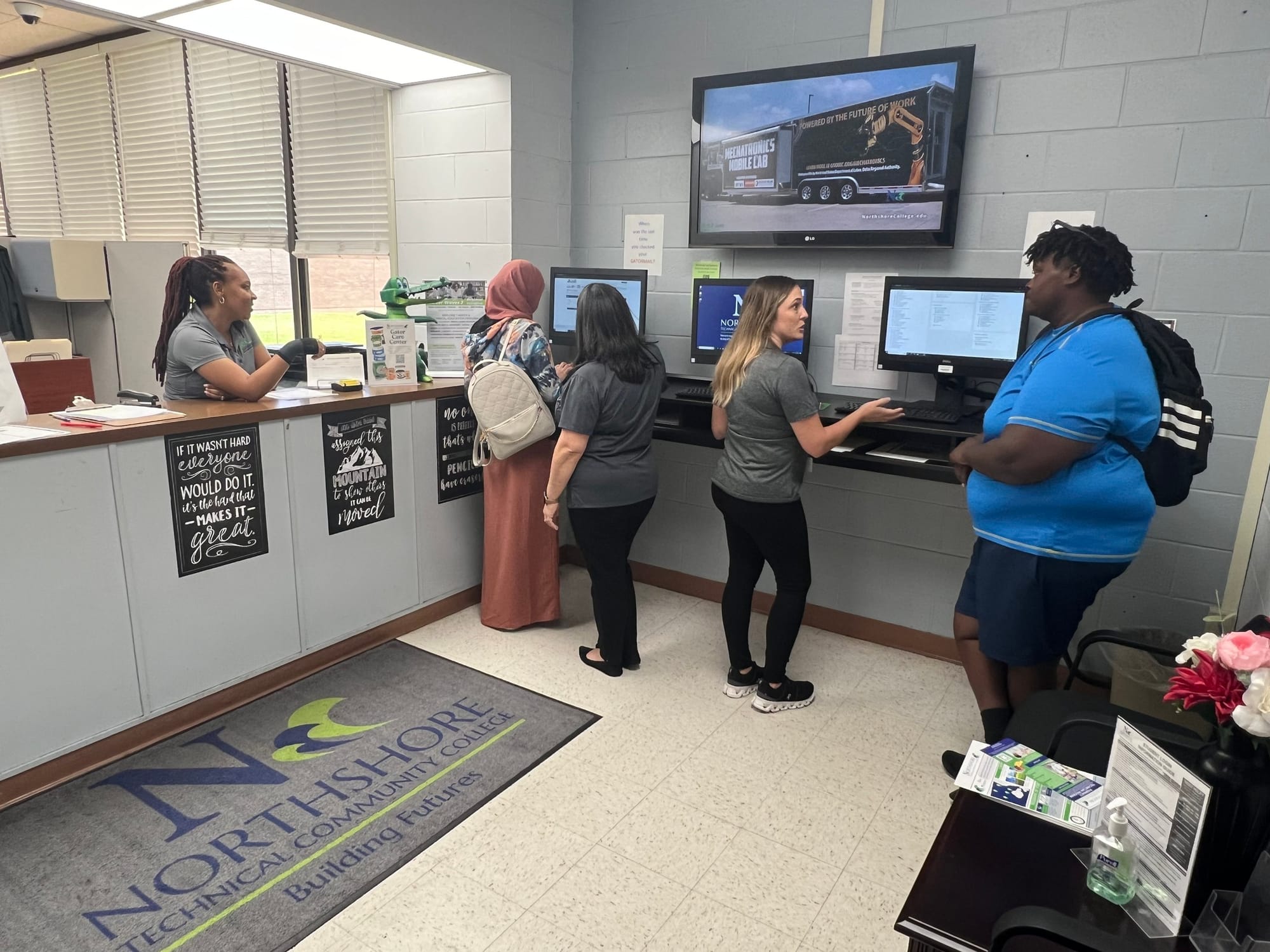

The public entities program is not advertised anywhere on the PSC website. It has received little press since it was created. Schools and other public agencies largely learn about the program like Lopez did, through a contractor who approaches them and offers to prepare an application to the appropriate commissioner.

Skrmetta calls it “free enterprise,” with contractors talking to local governments to find out what they need.

In the early years of the program, one of Skrmetta’s business partners in a film production company won most of the contracts, according to research done by Tait of the Energy and Policy Institute (EPI).

Since Tait blew the whistle on the relationship between Skrmetta and Jason Hewitt in 2020, Hewitt’s company, Brillant Efficiencies, no longer works with the program.

“After this article came out,” Hewitt told Floodlight in an email, “we simply could no longer do business in the program as the negative press was too much to overcome.”

But Hewitt’s company had problems long before the EPI report.

In early 2020, Commissioner Foster Campbell refused to pay Brilliant Efficiencies the full amount invoiced for a completed lighting project at Grambling State University after repeatedly instructing Brilliant Efficiencies over several years to scale back the scope of the project.

After Hewitt was awarded that contract, the Democratic commissioner implemented a bidding procedure in his district. His staff sought after-the-fact bids on the Grambling project, discovering “gaping price disparities” of up to $200,000 between Brilliant Efficiencies’ bid and other companies’ bids.

Hewitt defended his work in a 77-page response to Campbell, saying among other things that the price comparisons were unfair and citing “unexpected delays and costs” associated with the new program.

Skrmetta denied steering any business to Hewitt. Francis also denies favoritism in the program.

“It looks like we’ve just got a couple of special friends,” Francis said, “and that's just not the case at all.”

Floodlight reviewed campaign finance records from 2017 on, finding seven donations totalling $6,250 to three commissioners from contractors who got business through the public entities program.

A 2024 Floodlight investigation found Louisiana PSC members have cozy ties with the utilities they regulate, receiving nearly 43% of their campaign donations over the past 10 years — more than $8 million — from those companies and their allies. Louisiana law also lets commissioners engage in unreported private chats with representatives of the utilities they regulate — ”ex parte” communications that are banned or subject to strict reporting requirements in many other states, Floodlight found.

Burke says without a transparent selection process, entities without connections to the commissioners could be left out. “They are not selected on (the) most, greatest cost effectiveness,” she said. “It's simply unclear who, how and and why winners and losers are selected.”

Dearth of bidding raises questions

The bulk of the work is handled by just a few contractors, including Morris, who started his contracting firm, MM Energy Solutions, in 2020 after a career in health and fitness.

He quipped: “This is a lot easier than to try to convince a bunch of Cajun people to quit eating boudin, crackers and drinking beer.”

Morris says it’s the quality of his work — not his connections — that have led to contracts and subcontracts for more than 180 of the 515 projects approved.

“Mike Francis is not handing out stuff to me. I got to earn my business. I've always had to earn my business with these guys,” Morris said.

Campbell is the only commissioner who requires multiple bids for projects. In 2020, he introduced a motion to require bidding on all commission projects. It failed on a party-line 3-2 vote.

Lewis says his office has received letters from the utilities — which pay the public entities’ contractors directly — questioning some program costs. The three utilities declined to comment on any problems with the program.

“The utilities have been very clear that this program is not run correctly,” Lewis said, citing concerns over inflated costs for light bulbs and invoices that are not “fully correct.”

Lewis asked an Entergy Louisiana representative to discuss those issues at the PSC’s April meeting. But Larry Hand, Entergy’s vice president of regulatory affairs, demurred.

“Ultimately it is a commission-led program,” Hand said. “When we get the approval from the (commissioner’s) office and also from the (PSC) … that triggers our obligation to pay.”

Campbell says it’s up to the individual commissioners to make sure the job is done well “and not just take people’s word for it.” Campbell and Lewis have pushed for program reforms. Francis, the chairman, says he’s open to changes.

“If we get a majority of the commissioners say, ’Let's put more checks and balances on the public entity side,’ I won't disagree with that,” Francis said. “But right now, I feel comfortable with what kind of value we're getting for the money we're spending.”

Do you have information to share about Louisiana’s public entities energy efficiency program? Contact us by filling out this form. Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powers stalling climate action.