Coal was on its way out. But surging electricity demand is keeping it alive — costing customers and the planet

U.S. coal plant use is dropping, but utilities are delaying their retirement and running them — even when they cost more than renewable sources.

Published by WWNO, Wisconsin Watch

The Victor J. Daniel Jr. coal plant — now the largest electric generator in Mississippi — began pumping out power in 1977. In 2001, it got a second life, when owner Mississippi Power added two new turbines that could run on natural gas. Plant Daniel’s coal furnaces were supposed to shut down in 2027.

But now, the plant is slated for a third act. This year, Georgia Power won regulatory approval to buy power from that plant through 2028, due to what the utility called “unprecedented” growth in electricity demand.

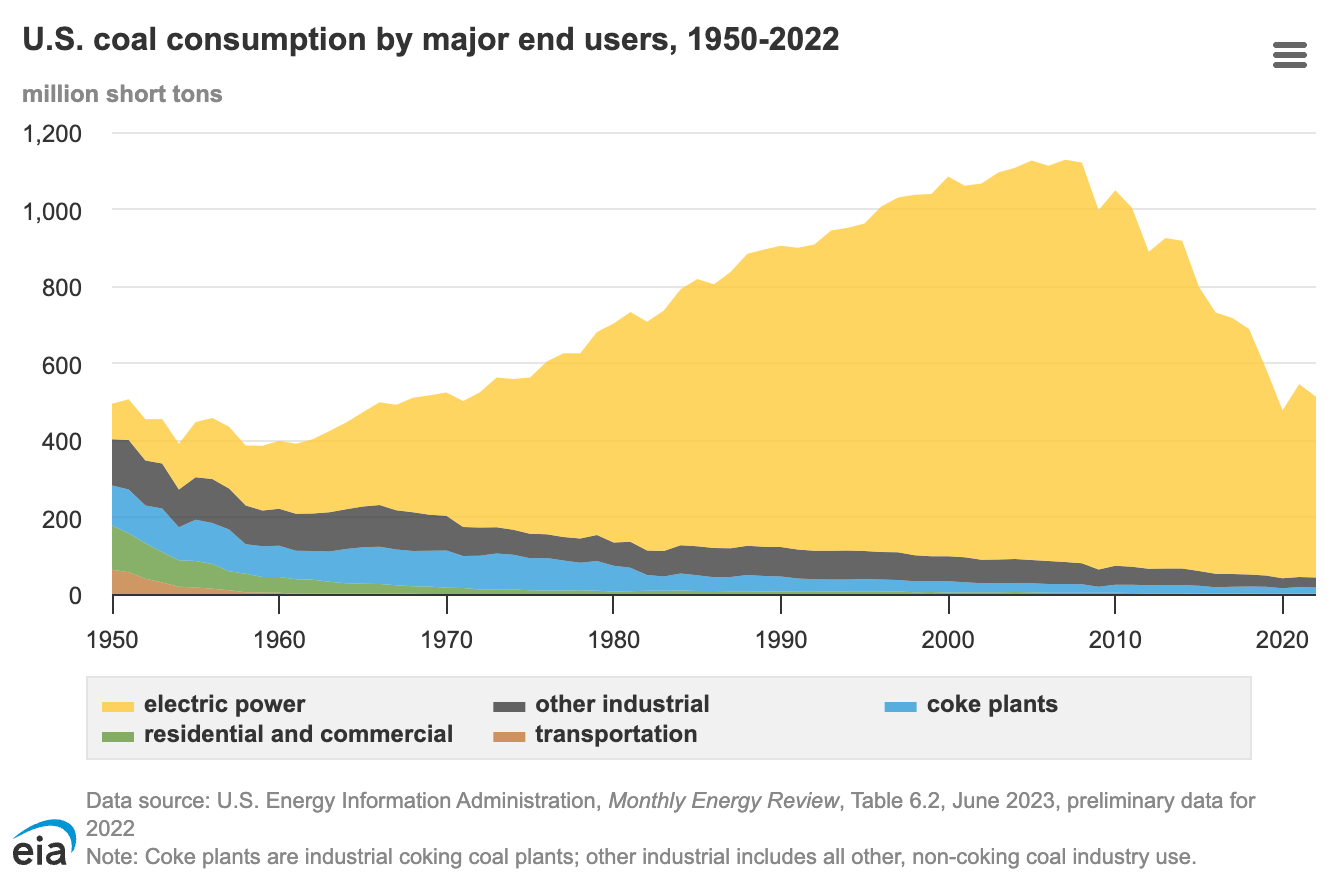

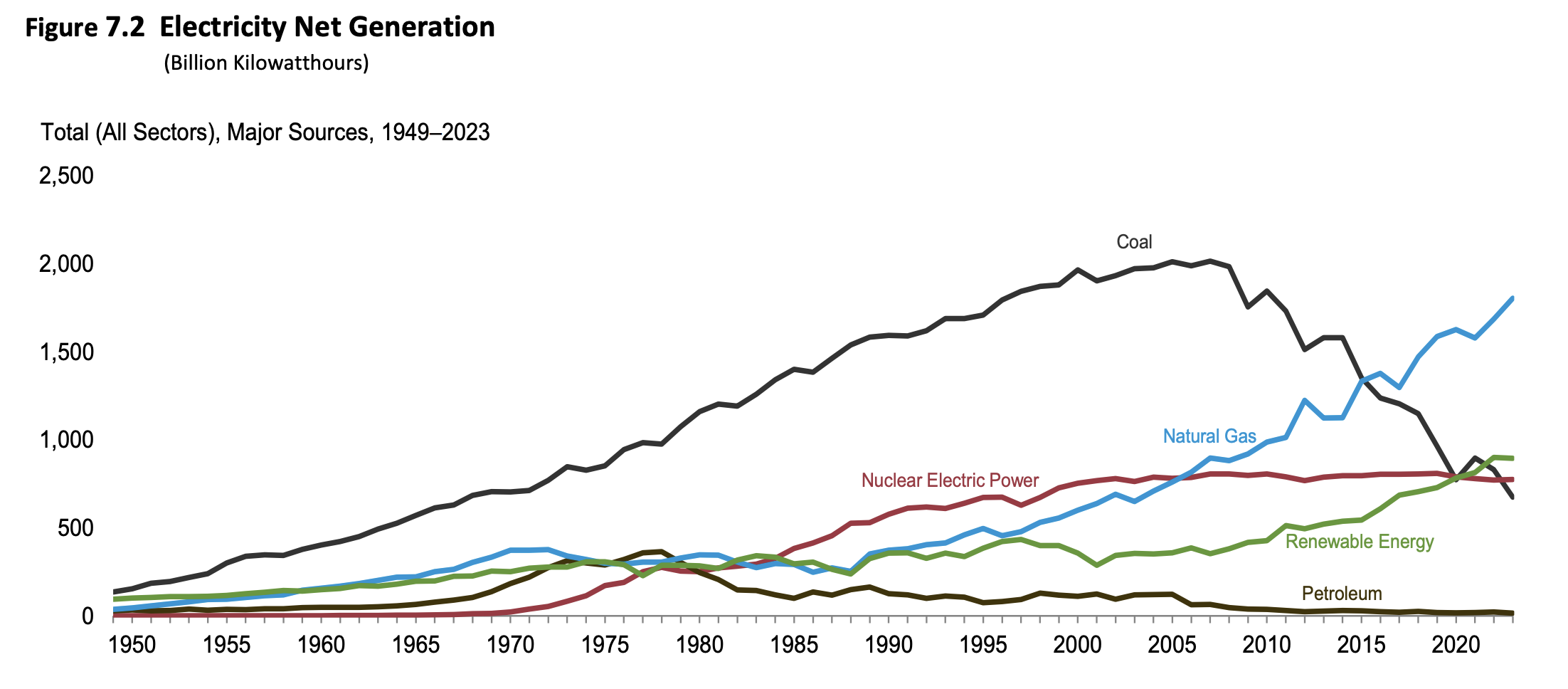

Coal-powered generation of electricity has steadily declined in the United States over the past 15 years, driven out by cheaper fuel sources including natural gas, wind and solar — cutting a main source of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

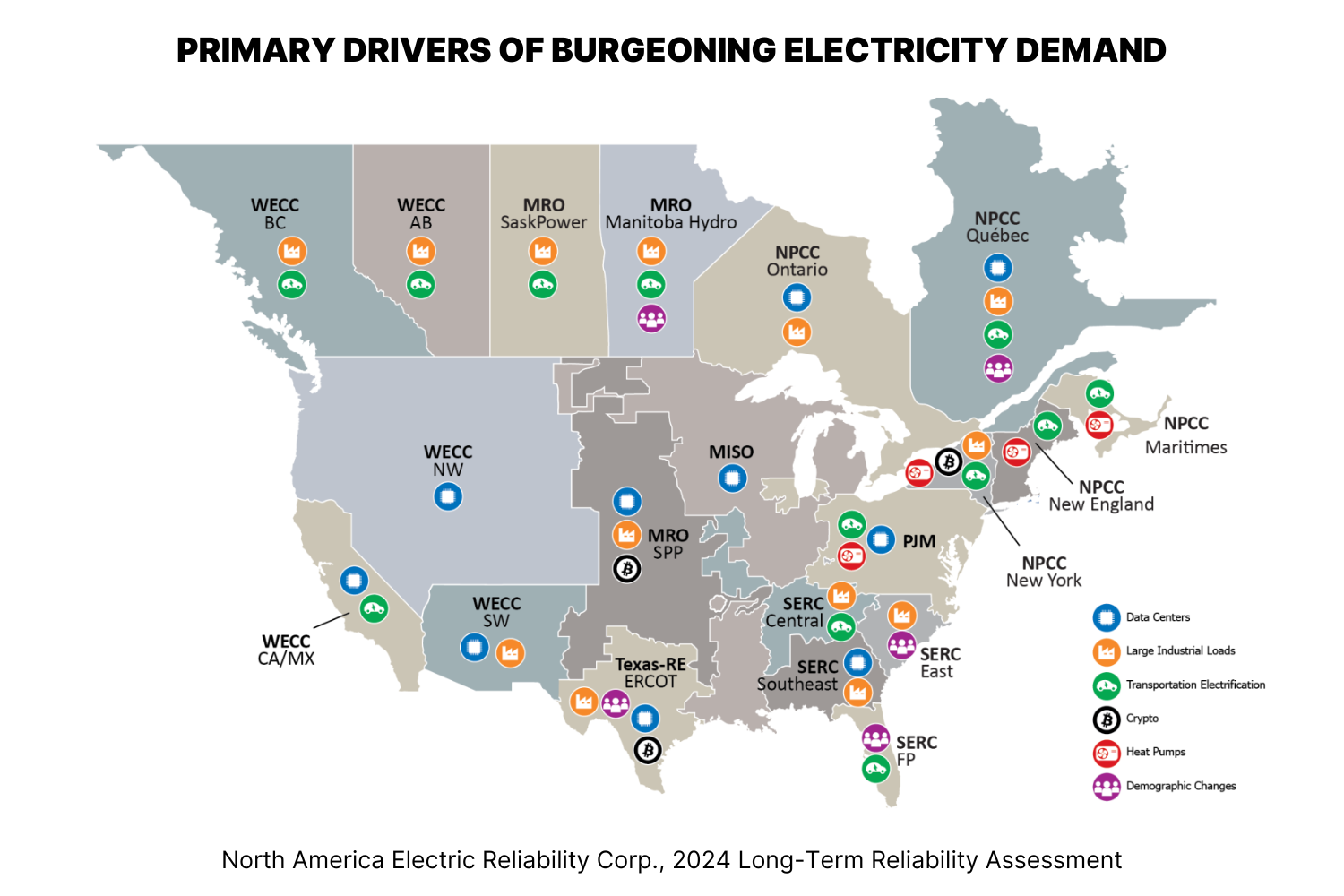

In the meantime, however, estimates of U.S. electricity demand in 2029 have increased nearly five-fold from those made just a few years ago, fueled by demand from data centers and other high-energy-using industries.

Many utilities see keeping coal around — including as a backup to intermittent power sources such as wind and solar — as a potential solution. A Floodlight analysis of power plant data shows that owners or operators of more than 30 U.S. coal plants, in states from Wisconsin to West Virginia, plan to delay their retirement, while others are weighing the option.

That is pushing up utility bills — and slowing progress on cutting dangerous greenhouse gas emissions.

Between 2015 and 2023, all of those 30-plus plants produced electricity “uneconomically,” adding more than $5 billion in unnecessary costs to customer rates, according to analysis by the Rocky Mountain Institute, a clean energy consultancy. For example, operating Mississippi Power’s Plant Daniel cost customers more than $250 million in excess costs during that time, according to RMI.

Allowing coal plants to run frequently, even when they are not the cheapest resource, is a fixture of modern electricity markets. Some environmental experts say it’s slowing the development of cleaner resources, while costing customers billions in direct costs and billions more in related health and environmental costs.

Concerns over those costs may take on new urgency amid the debate over growing electricity demand. Many utilities have said they’re unprepared to meet demand forecasts without keeping fossil fuel plants around longer.

“We really do have growth in demand and forecasts of growth that have not been seen really in the careers of most of the people who are working in the electric power world,” said Michael Jacobs, a senior energy analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “The real question is: Well, how did we get into this situation?”

He added, “Had we had the attention to following through on building the renewables, we would have a fraction of this debate going on.”

Anxiety around unprecedented load growth began in earnest only a couple of years ago spurred by large data centers used to fuel artificial intelligence models, cryptocurrency and other energy-intensive industries. The numbers around data center growth have been described as “staggering.” In a December report, the Department of Energy projected that U.S. energy use from data centers could double or even triple by 2028.

For utilities like Mississippi Power, that may mean longer lifetimes for coal. Mississippi Power declined to respond to specific questions about Plant Daniel, its expectations for load growth, or concerns about its uneconomic dispatch.

A spokesperson directed Floodlight to its 2024 Integrated Resource Plan, which lays out the utility’s expected mix of generation resources. That plan notes that some fossil units “considered marginally economic” are now in demand to fill gaps in capacity, and that the utility anticipates the buildout of several large data centers in its territory.

‘Used and useful?’

Utilities must meet electricity demand 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Because demand fluctuates, the United States has more power plants than needed at any one time. For about two-thirds of the electricity used in the United States, market operators, called regional transmission operators or independent system operators, decide which plants to call on based on how much demand they expect. They start with the cheapest plants and move to more expensive plants as demand increases. “You save the expensive ones for when you really need them,” Jacobs explained.

All plants that run get paid the amount — called the “clearing price” — that it costs to operate the most expensive facility that ends up running.

For more than a century, coal was the baseload of our generation fleet: the cheapest resource and the one meeting the majority of demand. But as U.S. gas production ballooned, natural gas overtook coal as the cheapest source of electricity generation in 2016.

Today, new wind and solar plants often beat out coal — and, at times, even gas — on price. As a result, a wave of retirements has hit the U.S. coal fleet. The plants that do remain are being used less and less, and coal now generates less than a fifth of U.S. electricity, down from nearly 45% in 2010.

But many holdout plants are still running.

That’s in part because plants can “self-commit” to run, even if operating them is more expensive than the clearing price. Often, those plants — and the utilities that own them — lose money when they self-commit. But utility regulations mean everyday electricity customers may be the ones picking up the tab.

In the majority of the United States, utilities are regulated monopolies: Customers must purchase electricity from them. Regulated utilities make money, in part, through a guaranteed “rate of return” on investments in equipment including power plants. Those returns are approved by regulators and paid by customer bills.

Utilities are required to show their plants are “used and useful” to get approval for including a plant in customer rates. And experts like Michael Goggin, vice president at energy consultancy Grid Strategies, say utilities may be dispatching coal even when it costs customers more to make a plant “look more used and useful than it actually is.”

In a 2024 report on “uneconomic dispatch” in the Midwest, Grid Strategies showed that 14% of 2023 coal plant starts by regulated utilities were unprofitable. Only 2% of coal starts from merchant plants, which earn fluctuating revenue based on the market, were unprofitable.

Without so-called uneconomic dispatch, customers could have saved more than $3 billion in 2023, according to RMI. In Louisiana, for example, regulators determined that electric utilities Cleco and SWEPCO had overcharged customers by $125 million by continuing to run the now-shuttered Dolet Hills coal-fired plant.

The consultancy also estimated that coal-related health impacts reached over $20 billion in 2023, for emergency room visits and diseases including lung cancer and cardiac disease that could have been avoided. That’s not to mention the hundreds of millions of tons of climate-damaging carbon dioxide these plants emit per year.

Delaying the clean energy transition?

Goggin argued the practice of making plants look more viable than they are may also keep them around longer, crowding out the transition to cleaner and cheaper energy.

“Having these coal plants in the way, that are pumping out uneconomic megawatt-hours and that are using up transmission capacity — in many cases in prime wind and solar spots — is impeding that,” he said.

Increasing demand may at least temporarily inflate electricity prices and push more coal plants into the black. But it also appears to leave an opening for later retirements.

All of the plants Floodlight identified with delayed timelines have already been producing power uneconomically for years. “Every year, there are less and less months, and less and less hours where it’s economic to run coal plants, and utilities have been dispatching these coal plants pretty similarly over the last 20 years,” said Gabriella Tosado, a senior associate with RMI’s carbon-free electricity program.

State utility regulators are responsible for ensuring that utilities only pass on prudent costs to their customers. In some places, that’s already happening. This year, the Michigan Public Service Commission rejected $11 million in costs to be passed on to customers due to a utility running more expensive coal plants. In Minnesota and Missouri, regulators have investigated the issue. But Tosado said more regulators should be scrutinizing utility arguments about keeping coal plants online.

In a working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, economists from Columbia University, the University of Arizona and Northwestern University showed that the current utility regulatory structure creates “potentially conflicting incentives,” resulting in less than half as much coal power retired as would be shuttered in a scenario designed to minimize cost.

But minimizing costs within current regulatory constraints is a challenge. The paper’s authors also found that a scenario that minimizes cost could reduce utility profits significantly enough to require external financial support to maintain electrical reliability.

In its report, the Department of Energy suggested connecting data centers to clean energy, rather than fossil fuels, including adding new generation on former coal plant sites.

And coal plants also don’t necessarily need to retire immediately; utilities may also consider running them during part of the year, when they are truly needed. Some utilities, like Minnesota’s Xcel Energy, have already pursued this route (some utilities are even speeding up coal retirements).

“It’s been my view that we don’t need to retire and dismantle every power plant that burns fossil fuels. We just need to be extraordinarily shy about burning fuel in them,” said Jacobs, who helped author a 2020 report on uneconomic dispatch. But, he added, “the utility practice of not facing up to competition, not wanting to deal with change, is not a strategy that’s going to work for society or the economy.”

Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.