Corn’s clean-energy promise is clashing with its climate footprint

Corn dominates U.S. farmland and fuels the ethanol industry. But the fertilizer it relies on drives emissions and fouls drinking water.

Co-published by The Guardian

For decades, corn has reigned over American agriculture. It sprawls across 90 million acres — about the size of Montana — and goes into everything from livestock feed and processed foods to the ethanol blended into most of the nation’s gasoline.

But a growing body of research reveals that America’s obsession with corn has a steep price: The fertilizer used to grow it is warming the planet and contaminating water.

Corn is essential to the rural economy and to the world’s food supply, and researchers say the problem isn’t the corn itself. It’s how we grow it.

Corn farmers rely on heavy fertilizer use to sustain today’s high yields. And when that nitrogen breaks down in the soil, it releases nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas nearly 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Producing nitrogen fertilizer also emits large amounts of carbon dioxide, adding to its climate footprint.

Agriculture accounts for more than 10% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, and corn uses more than two-thirds of all nitrogen fertilizer nationwide — making it the leading driver of agricultural nitrous oxide emissions, studies show.

The corn and ethanol industries insist that rapid growth in ethanol — which now consumes more than 40% of the U.S. corn crop — is a net environmental benefit, and they strongly dispute research suggesting otherwise.

Since 2000, U.S. corn production has surged almost 50%, further adding to the crop’s climate impact.

Yet the environmental costs of corn rarely make headlines or factor into political debates. Much of the dynamic traces back to federal policy — and to the powerful corn and ethanol lobby that helped shape it.

The Renewable Fuel Standard, passed in the mid 2000s, required that gasoline be blended with ethanol, a biofuel that in the United States comes almost entirely from corn. That mandate drove up demand and prices for corn, spurring farmers to plant more of it.

Many plant corn year after year on the same land. The practice, called “continuous corn,” demands massive amounts of nitrogen fertilizer and drives especially high nitrous oxide emissions.

At the same time, federal subsidies make it more lucrative to grow corn than to diversify. Taxpayers have covered more than $50 billion in corn insurance premiums over the past 30 years, according to federal data compiled by the Environmental Working Group.

Researchers say proven conservation steps — such as planting rows of trees, shrubs and grasses in corn fields — could sharply reduce these emissions. But the Trump administration has eliminated many of the incentives that helped farmers try such practices.

Experts say it all raises a larger question: If America’s most widely planted crop is worsening climate change, shouldn’t we begin growing it a different way?

Iowa corn farmer Levi Lyle uses a roller crimper to flatten cover crops, creating a mulch that suppresses weeds, feeds the soil and reduces or eliminates the need for fertilizer. (Video courtesy of Levi Lyle)

How corn took over America

Corn has been a staple of U.S. agriculture for centuries, first domesticated by Native Americans and later used by European immigrants as a versatile crop for food and animal feed. Its production really took off in the 2000s after federal mandates and incentives helped turn much of America’s corn crop into ethanol.

Corn’s dominance — and the emissions that come with it — didn’t happen by accident. It was built through a high-dollar lobbying campaign that continues today.

In the late 1990s, America’s corn farmers were in trouble. Prices had cratered amid a global grain glut and the Asian financial crisis. A 1999 report by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis said crop prices had hit “rock bottom.”

In 2001 and 2002, the federal government gave corn farmers and ethanol producers a boost — first through the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Bioenergy Program, which paid ethanol producers to increase their use of farm commodities for fuel. Then the 2002 Farm Bill created programs that continue to support ethanol and other renewable energy.

Corn growers soon after mounted an all-out campaign in Washington. Their goal: persuade Congress to require gasoline to be blended with ethanol. State and national grower groups lobbied relentlessly, pitching ethanol as a way to cut greenhouse gasses, reduce oil dependence and revive rural economies.

“We got down to a couple of votes in Congress, and the corn growers were united like never before,” recalled Jon Doggett, then the industry’s chief lobbyist, in an article published by the National Corn Growers Association. “I started receiving calls from Capitol Hill saying, ‘Would you have your growers stop calling us? We are with you.’ I had not seen anything like it before and haven’t seen anything like it since.”

Their persistence paid off. In 2005, Congress created the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS), which requires that a certain amount of ethanol be blended into U.S. gasoline each year. Two years later, lawmakers expanded it further. The policy transformed the market: The amount of corn used for ethanol domestically has more than tripled in the past 20 years.

When demand for corn spiked as a result of the RFS, it pushed up prices worldwide, said Tim Searchinger, a researcher at Princeton University’s School of Public and International Affairs. The result, Searchinger said, is that more land around the world got cleared to grow corn. That, in turn, resulted in more emissions.

That lobbying brought clout. “King Corn” became a political force, courted by presidential hopefuls and protected by both parties. Since 2010, national corn and ethanol trade groups have spent more than $55 million on lobbying and millions more on political donations, according to campaign finance records analyzed by Floodlight.

In 2024 alone, those trade groups spent twice as much on lobbying as the National Rifle Association. Major industry players — Archer Daniels Midland, Cargill and ethanol giant POET among them — have poured even more into Washington, ensuring the sector’s voice remains one of the loudest in U.S. agriculture.

Now those same groups are pushing for the next big prize: expanding higher-ethanol gasoline blends and positioning ethanol-based jet fuel as aviation’s “low-carbon” future.

Research undercuts ethanol’s clean-fuel claims

Corn and ethanol trade groups didn’t make their officials available for interviews.

But on their websites and in their literature, they have promoted corn ethanol as a climate-friendly fuel.

The Renewable Fuels Association cites government and university research that finds burning ethanol reduces greenhouse gas emissions by roughly 40-50% compared with gasoline. The ethanol industry says the climate critics have it wrong — and that most of the corn used for fuel comes from better yields and smarter farming, not from plowing up new land. The amount of fertilizer required to produce a bushel of corn has dropped sharply in recent decades, they say.

“Ethanol reduces carbon emissions, removing the carbon equivalent of 12 million cars from the road each year,” according to the Renewable Fuels Association.

Growth Energy, a major ethanol trade group, said in a written statement to Floodlight that U.S. farmers and biofuel producers are “constantly finding new ways to make their operations more efficient and more environmentally beneficial,” using things like cover crops to reduce their carbon footprint.

"Biofuel producers are making investments today that will make their products net-zero or even net negative in the next two decades," the statement said.

But some research tells a different story.

A recent Environmental Working Group report finds that the way corn is grown in much of the Midwest — with the same fields planted in corn year after year — carries a heavy climate cost.

Left: Cattle and other livestock eat more than 40% of the corn grown in the United States. A similar amount is used to make ethanol. Just 12% ends up as food for people or in other uses. (Dee J. Hall / Floodlight) | Right: The Renewable Fuel Standard, passed in the mid 2000s, requires that gasoline be blended with ethanol, which in the United States comes almost entirely from corn. That mandate drives up demand and prices for corn, spurring farmers to plant more of it. Ethanol producers say that was good for the climate, but recent research has concluded otherwise. (Ames Alexander / Floodlight)

Research in 2022 by agricultural land use expert Tyler Lark and colleagues links the Renewable Fuel Standard to expanded corn cultivation, heavier fertilizer use, worsening water pollution and increased emissions. Scientists typically convert greenhouse gasses like nitrous oxide and methane into their carbon-dioxide equivalents — or carbon intensity — so their warming impacts can be compared on the same scale.

“The carbon intensity of corn ethanol produced under the RFS is no less than gasoline and likely at least 24% higher,” the authors concluded.

Lark’s research has been disputed by scientists at Argonne National Laboratory, Purdue University and the University of Illinois, who published a formal rebuttal arguing the study relied on “questionable assumptions” and faulty modeling — a charge Lark’s team has rejected.

A 2017 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that the RFS was unlikely to meet its greenhouse gas goals because the U.S. relies predominantly on corn ethanol and produces relatively little of the cleaner, advanced biofuels made from waste.

The problem isn’t just emissions, researchers say. Corn ethanol requires millions of acres that could instead be used for food crops or more efficient energy sources. One recent study found that solar panels can generate as much energy as corn ethanol on roughly 3% of the land.

“It’s just a terrible use of land,” Searchinger, the Princeton researcher, said of ethanol. “And you can't solve climate change if you’re going to make such terrible use of land.”

Most of the country’s top crop isn’t feeding people. More than 40% of U.S. corn goes to ethanol. A similar amount is used to feed livestock, and just 12% ends up as food or in other uses.

As corn production rises, so have emissions

Globally, corn production doubled from 2000 to 2021.

That growth has been fueled by fertilizer, which emits nitrous oxide that can linger in the atmosphere for more than a century. That eats away at the ozone layer, which blocks most of the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation.

Global emissions have soared alongside corn production. Between 1980 and 2020, nitrous oxide emissions from human activity climbed 40%, the Global Carbon project found.

In the United States, nitrous oxide emissions from agriculture in 2022 were equal to roughly 262 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, according to the EPA’s inventory of greenhouse gas emissions. That’s equivalent to putting almost 56 million passenger cars on the road.

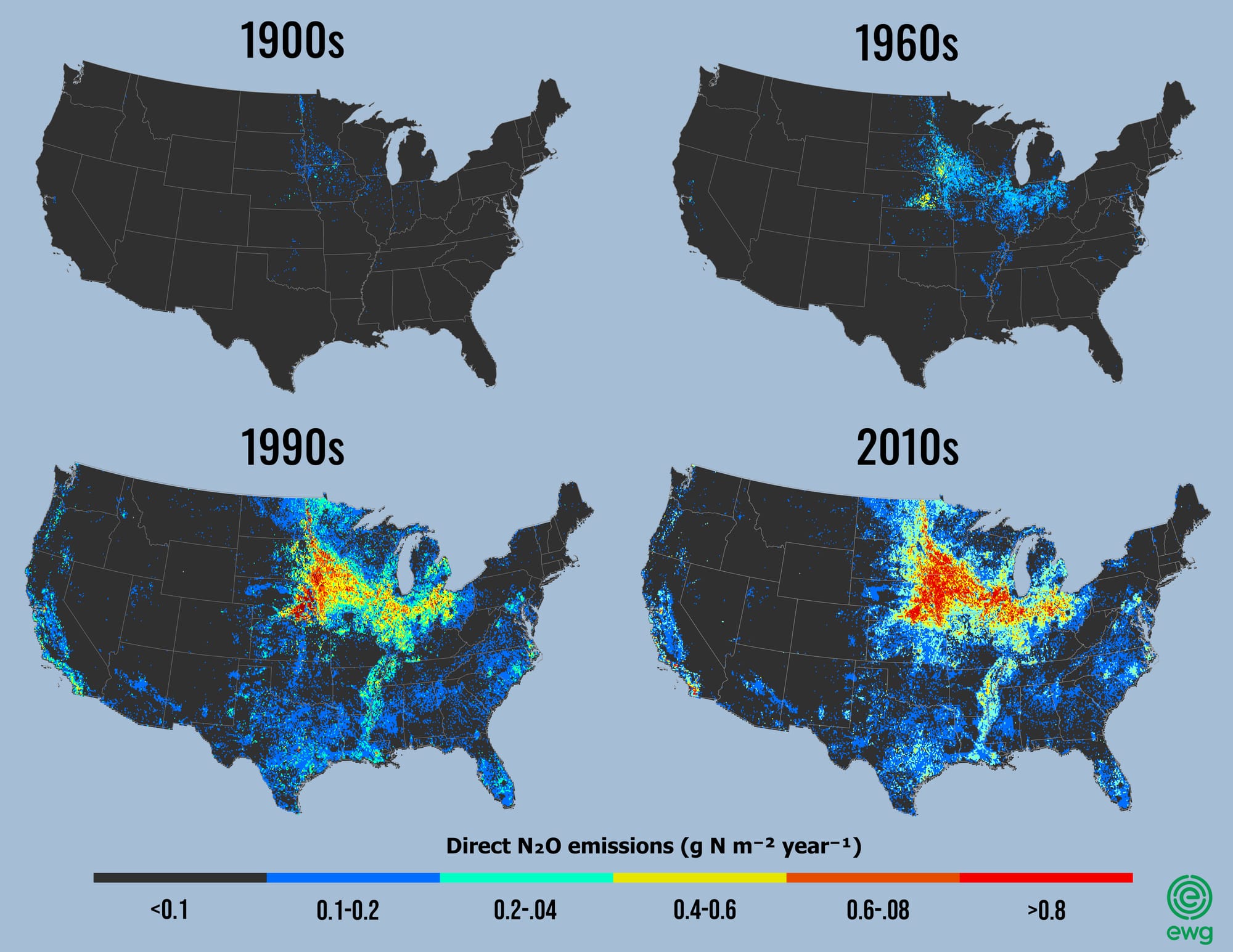

The biggest increases are coming straight from the Corn Belt.

Ethanol’s climate footprint isn’t the only concern. The nitrogen used to grow corn and other crops is also a key source of drinking water pollution.

According to a new report by the Alliance for the Great Lakes and Clean Wisconsin, more than 90% of nitrate contamination in Wisconsin’s groundwater is linked to agricultural sources — mostly synthetic fertilizer and manure.

The same analysis estimates that in 2022, farmers applied more than 16 million pounds of nitrogen beyond what crops needed, sending runoff into wells, streams and other water systems.

For families like Tyler Frye’s, that hits close to home. In 2022, Frye and his wife moved into a new home in the rural village of Casco, Wisconsin, about 20 miles east of Green Bay. A free test soon afterward found their well water had nitrate levels more than twice the EPA’s safe limit. “We were pretty shocked,” he said.

Frye installed a reverse-osmosis system in the basement and still buys bottled water for his wife, who is breastfeeding their daughter, born in July.

One likely culprit, he suspects, are the cornfields less than 200 yards from his home.

“Crops like corn require a lot of nitrogen,” he said. “A lot of that stuff, I assume, is getting into the well water and surface water.”

When he watches manure or fertilizer being spread on nearby fields, he said, one question nags him: “Where does that go?”

What cleaner corn could look like

Reducing corn’s climate footprint is possible — but the farmers trying to do it are swimming against the policy tide.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act, backed by President Donald Trump and congressional Republicans, strips out the provisions of President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act that had rewarded farmers for climate-friendly practices.

And in April, Trump’s USDA canceled the $3 billion Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities initiative, a grant program designed to promote farming and forestry practices to improve soil and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The agency said that the program’s administrative costs meant too little money was reaching farmers, while Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins dismissed it as part of the “green new scam.”

University of Iowa professor Silvia Secchi said the rollback of the Climate-Smart program has already given farmers “cold feet” about adopting conservation practices. “The impact of this has been devastating,” said Secchi, a natural resources economist who teaches at the university’s School of Earth, Environment and Sustainability.

Research shows what’s possible if farmers had support. In its recent report, the Environmental Working Group found that four proven conservation practices — including planting trees, shrubs and hedgerows in corn fields — could make a measurable difference.

Implementing those practices on just 4% of continuous corn acres across Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota and Wisconsin would cut total greenhouse gas emissions by the equivalent of taking more than 850,000 gasoline cars off the road, EWG found.

Despite setbacks at the federal level, some farmers are already showing what a more climate-friendly Corn Belt could look like.

In northern Iowa, Wendy Johnson farms 1,200 acres of corn and soybeans with her father. On 130 of those acres, she’s trying something different: She’s planting fruit and nut trees, organic grains, shrubs and other plants that need little or no nitrogen fertilizer.

“The more perennials we can have on the ground, the better it is for the climate,” she said.

Across the rest of the farm, they enrich the soil by rotating crops and planting cover crops. They’ve also converted less productive parts of the fields into “prairie strips” — bands of prairie grass that store carbon and require no fertilizer.

Under the now-cancelled Climate-Smart grant program, they were supposed to receive technical assistance and about $20,000 a year to expand those practices. The grant program was terminated before they got any of the money.

“It’s hard to take risks on your own,” Johnson said. “That’s where federal support really helps. Because agriculture is a high-risk occupation.”

Left: Iowa farmer Levi Lyle planted this corn in soil with mulch made from cover crops instead of synthetic fertilizer. This type of mulch suppresses weeds, enriches soil and reduces or eliminates the need for nitrogen fertilizer. It’s a “huge opportunity to sequester more carbon, improve soil health, save money on chemicals and still get a similar yield,” Lyle says. (Photo courtesy of Levi Lyle) | Right: This ear of corn is part of a larger climate story: Nitrogen fertilizer — which is used heavily in Corn Belt states like Wisconsin — is driving a surge in nitrous oxide emissions, a potent greenhouse gas. (Dee J. Hall / Floodlight)

The economics still favor business as usual. Johnson knows that many Midwestern corn growers feel pressure to maximize yields, keeping them hooked on corn — and nitrogen fertilizer.

“I think a lot of farmers around here are very allergic to trees,” she joked.

In southeast Iowa, sixth-generation farmer Levi Lyle, who mixes organic and conventional methods across 290 acres, uses a three-year rotation, extensive cover crops and a technique called roller-crimping — flattening rye each spring to create a mulch that suppresses weeds, feeds the soil and reduces fertilizer needs.

“The roller crimping of cover crops is a huge, huge opportunity to sequester more carbon, improve soil health, save money on chemicals and still get a similar yield,” he said.

But farmers get few government incentives to take such climate-friendly steps, Lyle said. “There is a lack of seriousness about supporting farmers to implement these new practices,” he said.

And without federal programs to offset the risk, the innovations that Lyle and Johnson are trying remain exceptions — not the norm.

Many farmers still see prairie strips or patches of trees as a waste, said Luke Gran, whose company helps Iowa farmers establish perennials.

“My eyes do not lie,” Gran said. “I have not seen extensive change to cover cropping or tillage across the broad acreage of this state that I love.”

The next corn boom?

Despite mounting research about corn’s climate costs, industry groups are pushing for policies to boost ethanol demand.

One big priority: Pushing a bill to require that new cars are able to run on gas with more ethanol than what’s commonly sold today.

Corn and biofuel trade groups have also been pressing Democrats and Republicans in Congress for legislation to pave the way for ethanol-based jet fuel. While use of such “sustainable” aviation fuel is still in its early stages domestically, corn and biofuel associations have made developing a market for it a top policy priority.

Secchi, the Iowa professor, says it’s easy to see why ethanol producers are trying to expand their market: The growth in electric vehicles threatens long-term gasoline sales.

Researchers warn that producing enough ethanol-based jet fuel could trigger major land-use shifts. A 2024 World Resources Institute analysis found that meeting the federal goal of 35 billion gallons of ethanol jet fuel would require about 114 million acres of corn — roughly 20% more corn acreage than the U.S. already plants for all purposes. That surge in demand, the authors concluded, would push up food prices and worsen hunger.

Secchi calls that scenario a climate and land-use “disaster.” Large-scale use of ethanol-based aviation fuel, she said, would mean clearing even more land and pouring on even more nitrogen fertilizer, driving up greenhouse gas emissions.

“The result,” she said, “would be essentially to enshrine this dysfunctional system that we created.”

Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powers stalling climate action.

Thanks for reading. Join us on Instagram for more video investigations: