Federal funds for methane-cutting digesters in farms could end up boosting methane emissions

The Inflation Reduction Act is offering millions to farmers to reduce the harmful greenhouse gas. Critics warn it encourages bigger farms.

Published by Environmental Health News, Investigate Midwest

In 2021, President Joe Biden signed the Global Methane Pledge, a commitment from 155 countries to reduce their country’s methane emissions by 30% by 2030. With just six years to go, the United States is falling short of that goal.

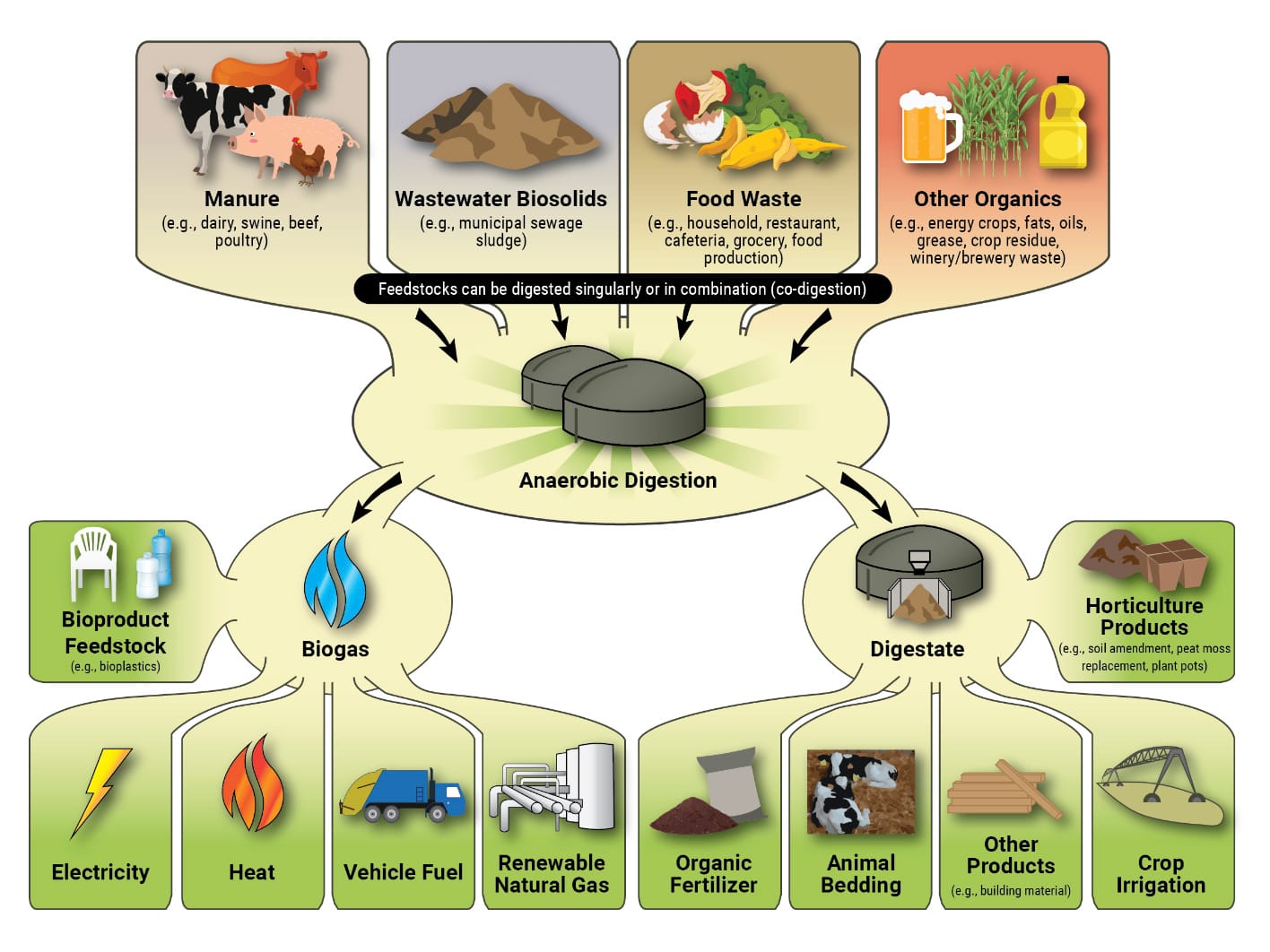

But the Biden Administration is championing a technology deemed a “game-changer” in cutting methane emissions: anaerobic digestion. Digesters are enclosed structures that break down manure and other organic waste and turn it into biogas that can be used for electricity, heat or fuel. Through the Inflation Reduction Act, Biden has provided millions of dollars for anaerobic digesters to be built on agricultural operations across the country.

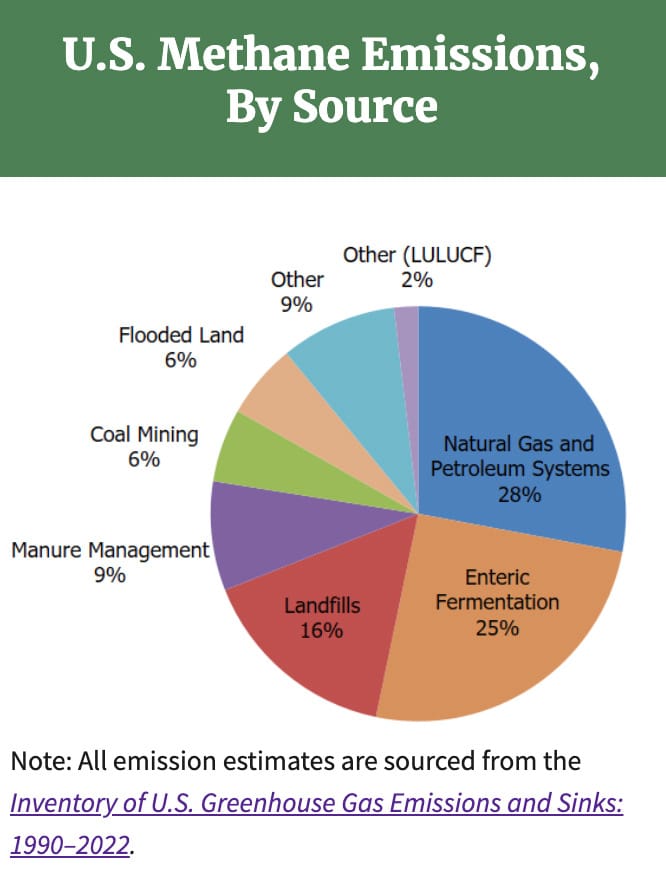

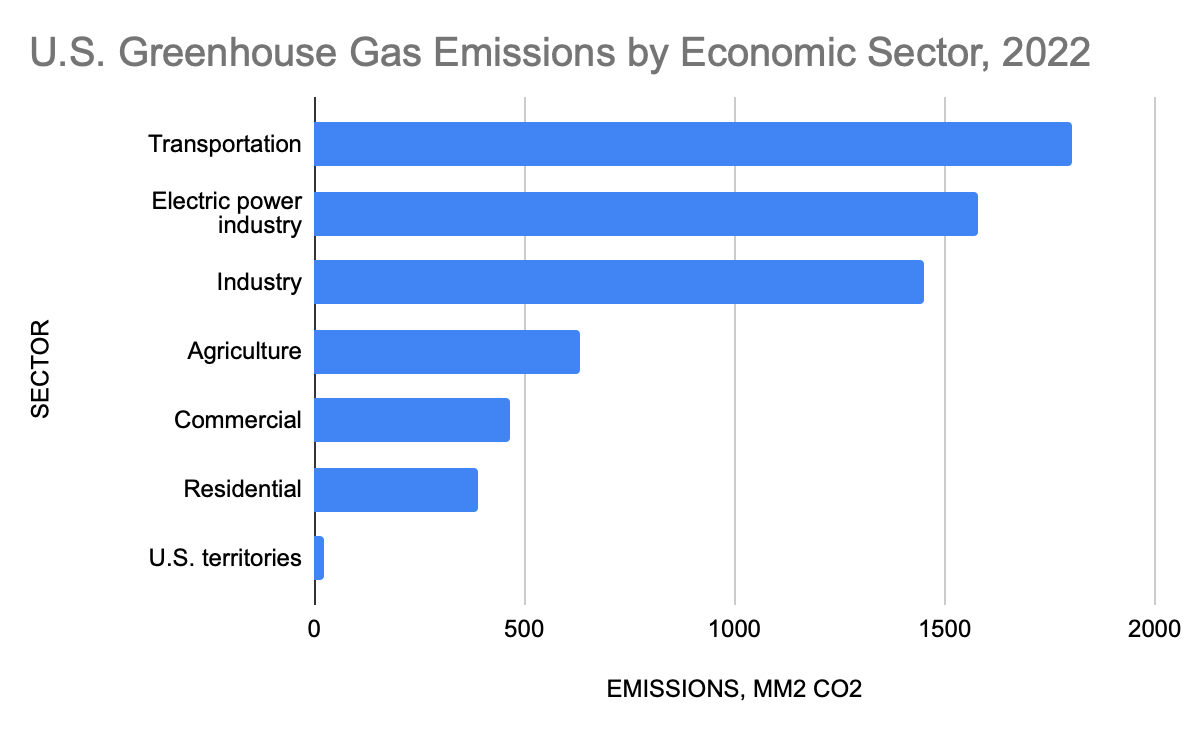

Agriculture is the leading source of methane pollution in the United States, and many in the sector have hailed anaerobic digesters as the best way to quickly cut methane emissions. Others however, say anaerobic digestion allows industrial-scale agriculture to operate business as usual, enabling farms to continue practices leading to more methane in the long run.

“Cutting methane quickly is the best lever we have to slow global warming in the next couple decades. Digesters are the single most effective tool in our toolbox,” says Michael Lerner, the director of research at Energy Vision, a nonprofit that focuses on methane reduction.

Methane is a greenhouse gas commonly found in landfills, sewer systems and organic waste, and is 28 times as potent as carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere over 100 years — and 80 times worse over 20 years.

Agriculture accounts for about one-third of the nation’s total methane emissions — and digesters are a “pragmatic solution” to cut that number, Lerner says.

In a report released in May, Energy Vision found that building an additional 4,000 anaerobic on-farm digesters would cut total net U.S. methane emissions by 6.1% annually.

IRA grants and loans have helped fund over 40 anaerobic digester projects since November through the Rural Energy for America Program (REAP), the majority of which will be implemented on dairy farms. REAP was designed to help agricultural producers and small business owners make renewable energy investments. From 2022 to 2027, the IRA will have dedicated over $1 billion to grants and loans under REAP.

Jim Muir, the director of development and marketing at Agricultural Digesters LLC, says funding from the IRA was a “tremendous asset” to some of the digester projects he works on. Muir’s Vermont-based company works with farmers to implement farmer-owned anaerobic digester systems that generate biogas.

For digesters to be cost-effective, they are usually implemented on farms with over 500 head of cattle or 2,000 hogs. But Muir wants to bring digesters to mid-size farms by combining two kinds of natural waste in one digester: manure and food waste. By bringing food waste from local landfills to mid-size farms and combining that waste with manure, two sources of methane emissions can be composted and provide revenue to struggling family farmers, Muir explains.

If 4,700 digesters for food waste and animal manure combined were built, together this would cut a total of 13.6% U.S. methane emissions, Energy Visions’ report found.

More cows = more methane

But not everyone is convinced. While digesters may minimally reduce emissions in the short term, they are not an effective long-term solution, says Molly Armus, the animal agriculture policy manager at Friends of the Earth (FOE). In the group’s recent report, FOE found that dairy operations that installed digesters increased their herd sizes by 3.7% each year — or 24 times the growth of dairies without digesters.

A larger herd size not only means more manure, it also means more methane from enteric fermentation — or cow burps — which digesters do not address, Armus explains. Enteric methane emissions from ruminant animals including cows, sheep and goats raised for meat and dairy production account for 30% of methane emissions worldwide.

To feed an anaerobic digester, there must be a certain amount of manure produced to begin with, Armus explains.

“By incentivizing biogas production you’re incentivizing the creation of methane emissions,” she says.

Reducing herd sizes and implementing alternative manure management strategies could result in 55% of the reductions needed to meet the Global Methane Pledge and would also be more cost effective, the FOE report found.

Along with funding digesters through REAP, the IRA funded a number of digesters through the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) a voluntary program designed to help farmers implement climate-friendly practices on their farm.

A variety of sustainable agriculture practices can be funded through EQIP grants, but anaerobic digester projects are the most expensive, averaging around $400,000 per project, according to a report by the Institute for Agriculture Trade Policy (IATP).

Rather than dedicating so much money to implement digesters, the focus should be lowering methane emissions on farms to begin with by reducing herd sizes and regulating CAFO emissions, says Ben Lilliston, the director of rural strategies and climate change at IATP.

“They’re not getting to the heart of the problem, which is: This CAFO model is high emitting. It’s not just the manure, it’s not just the cows, it’s also all the feed production which usually requires a lot of nitrogen fertilizer, which is another source of major emissions,” Lilliston said. “It’s a highly polluting system, and what you have is powerful industries that do not want to really break out of that system, they want to maintain it.”

But with the pressure to lower methane emissions immediately, systemic change in the short term could be out of reach. While reducing herd sizes is ideal, there are still thousands of mega-farms emitting large amounts of methane, and digesters are a quick, effective solution, Lerner of Energy Vision says.

“We recognize that these kinds of large herd sizes have a whole litany of issues. But the reality that confronts us is we need to cut methane now,” Lerner says. “These farms exist, they're entrenched in places across the country. A lot of money has been sunk into them, and it would take a lot longer to downsize the industry. We don't have the luxury of time to wait for that to happen.”

This story is part of an occasional series examining the climate impact of the Inflation Reduction Act.