Environmental groups sue over Louisiana’s ban on community air monitoring

Meanwhile, a state task force’s call for beefed up air monitoring in areas affected by industrial pollution appears to be falling on deaf ears.

Published by Louisiana Illuminator.

Six grassroots environmental groups filed a federal lawsuit this week that takes aim at a 2024 Louisiana law that essentially crippled community-based air monitoring in the state.

The suit, filed Thursday in the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Louisiana, calls the law an “industry-friendly ban” that bars groups from using their own independent air monitoring systems to warn residents living in fenceline communities about potential health risks.

“Our legislature and officials should do everything in their power to stop industry from polluting our air in the first place,” said Joy Banner, co-founder of The Descendants Project, one of the six plaintiffs in the lawsuit. “To attack our First Amendment rights instead is arcane, illegal and dangerous.”

The coalition’s lawsuit argues that Louisiana’s air monitoring law suppresses evidence collected by more affordable air quality monitoring equipment that they use to help “fenceline” communities better understand the quality of the air they’re breathing.

The lawsuit alleges the law does this by preventing the use of this data to allege air quality violations, with penalties of up to $32,500 a day, plus $1 million for intentional violations. The plaintiffs argue this violates their right to free speech.

The lawsuit comes at a time when a new report from a special legislative task force is urging Louisiana lawmakers to invest millions more in monitoring and real-time notification of hazardous emissions in communities hardest hit by pollution.

The Bayou State is one of the most industrialized in the United States, with 476 major air pollution sources — including petroleum, chemical, plastics and sugar facilities — as defined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The recommendations from a special legislative task force come nearly a year after lawmakers crippled Louisiana grassroot organizations’ efforts to do their own analysis of air quality. The law they passed prohibits data collected from community-run air monitoring programs from being used in enforcement, lawsuits or regulatory actions.

The task force was made up of state environmental officials, industry lobbyists and representatives from the nonprofit environmental group that was a target of the new law, which set standards for air monitoring so high that grassroots groups can’t meet them.

The report submitted last month to the House and Senate legislative environmental committees recommends that lawmakers spend at least $13 million to establish a more robust and localized air monitoring and notification system within the state’s Department of Environmental Quality.

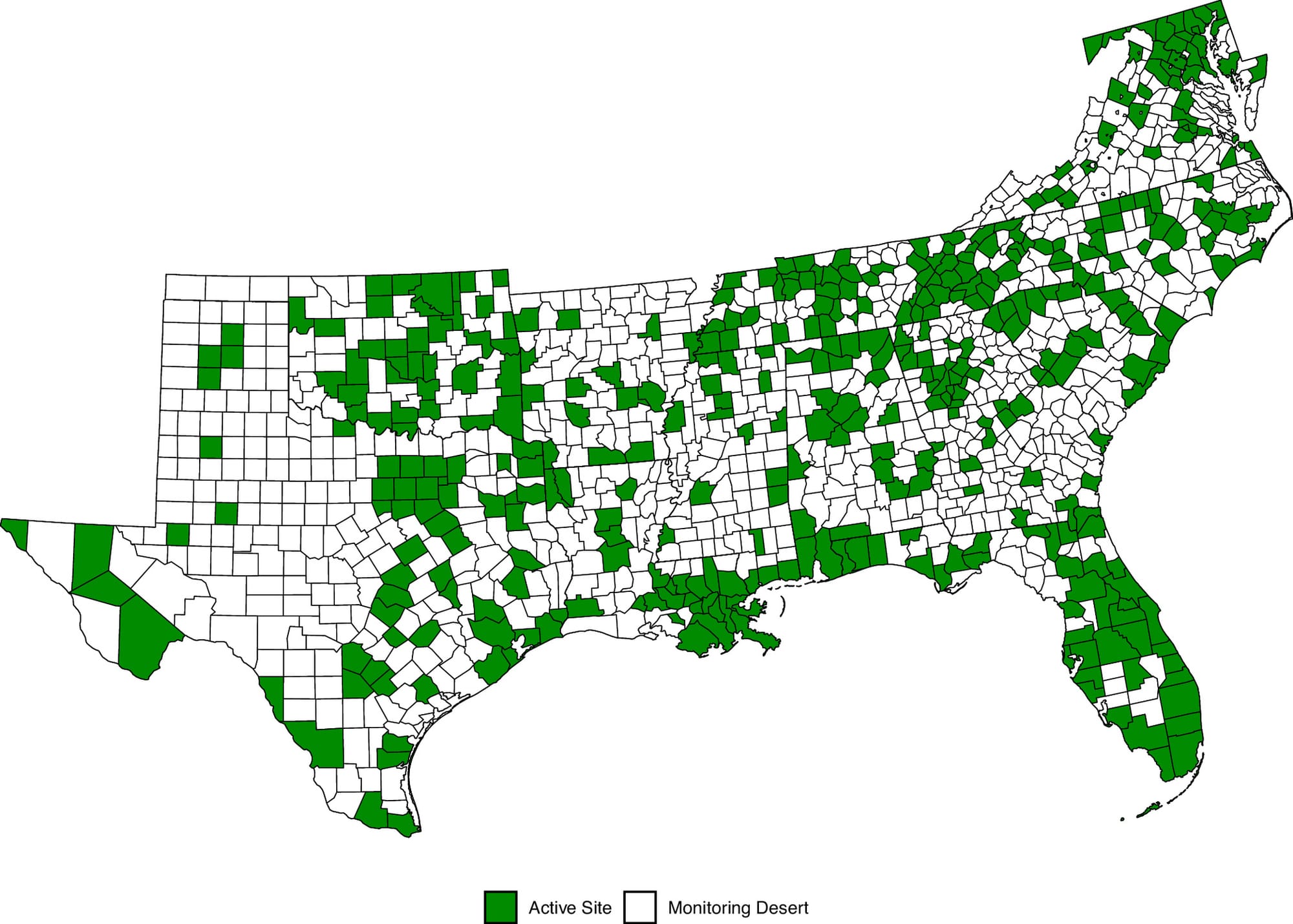

LDEQ’s current system consists of 29 continuous monitoring sites that report annually to the EPA and track real-time data on emissions — including particulate matter, carbon monoxide, ozone, sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides. It also operates seven non-continuous monitoring sites that help the agency track long-term trends in air quality. And it has four temporary monitoring sites that can be strategically placed in areas of concern, generally collecting a year of data in each location.

The report recommends that LDEQ place additional air monitors near the top polluting industrial facilities in the state based on the volume and toxicity of their emissions and their proximity to “fenceline” communities. The committee estimated these regulatory monitors would cost nearly $800,000 per site and between $150,000 to $200,000 in annual operating and maintenance expenses.

It suggested the state could locate them near 10% to 20% of Louisiana’s major air pollution sources — which would mean tens of millions of dollars just in capital costs.

In addition to more monitoring, the task force recommends a notification system capable of blasting out real-time text and phone call alerts about possible air quality dangers to nearby residents. Such a notification system has an estimated price tag of $5.2 million for initial set up and annual maintenance.

The recommendations would require LDEQ to hire 48 new people, to join the team of seven currently dedicated to overseeing the data collected by the existing network of monitoring sites, at an annual cost of about $8.2 million.

Louisiana leaders mum on more monitoring

But there’s no indication yet from state leaders or LDEQ that money will be allocated to implement the report’s recommendations. The Republican chairs of Louisiana’s Senate Environmental Quality Committee and House committee on Natural Resources and Environment did not respond to questions from Floodlight about the report. Inquiries to officials with LDEQ also went unanswered.

“I would hope that the Legislature would believe that having information that affects people's health, affects workers’ health and affects communities would be an important priority for them,” said Marylee Orr, executive director of the Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN).

LEAN had a seat on the 11-member task force that drafted the report. The organization received $500,000 in federal funding allocated for community-run air monitoring programs in former President Joe Biden’s 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

LEAN used the money to deploy a fleet of mobile air-monitoring vehicles that collected samples along the Mississippi River area in southwest Louisiana known as “Cancer Alley.” The group also has partnered with a bulk storage facility for liquids — including ethanol, diesel and other petroleum products — in St. Rose, Louisiana, to monitor air quality in nearby neighborhoods.

Localized, coordinated air monitoring efforts like LEAN’s have been a tool marginalized communities overburdened by polluting industries have tried to demonstrate air quality problems and push state leaders for tougher regulations and enforcement of the Clean Air Act.

Orr said LEAN favors this latest step urging the Legislature to act but, “I don't know where the money's going to be coming from.”

Current system seen as inadequate

Environmental advocates have long criticized Louisiana’s existing air monitoring system, calling it insufficient to accurately measure pollution since there aren’t enough monitors located where air quality is the most compromised.

The state ranks fourth highest among 56 states and territories for toxic emissions per square mile, according to EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory. Roughly 400 Louisiana facilities emitted 132 million pounds of toxic pollution in 2022.

Chet Wayland, former director of the EPA’s Air Quality Assessment Division, said most states’ air monitoring systems are designed to meet the minimum standards for ambient air. That means not necessarily putting them near industrial facilities, but rather in more densely populated places to measure air pollutants including particulate matter, ozone and sulfur dioxide, he said.

Wayland said states can increase air quality oversight through community-based air monitors. He said such localized air monitoring, as California and New York use, is the best way to track the emissions of the more dangerous air toxins like benzene, toluene, heavy metals and industrial solvents.

“We all would love to see more data available. Clearly we can't monitor every single place that we should be monitoring. The resources aren't there from the federal standpoint and — I get it — they're not there from the state standpoint as well,” Wayland said.

He said a “smart strategy” would be to place monitors in places where people are more likely to be exposed to harmful air pollutants, adding, “It would be nice to have some indication of what the air quality is in those areas.”

The task force report also suggests supplementing new monitors with air quality sensors that are cheaper and could detect pollutants wafting through communities. The report acknowledges these air sensors are “prone to inaccuracies” and are most useful for offering general insight into air quality — not as a resource for enforcement.

Future of federal funding in question

Nationally, approximately $117 million was earmarked in the IRA for state, local governments, tribal nations and community groups to implement, upgrade and continue various air monitoring programs in fenceline communities.

But Romany Webb, deputy director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, noted that Congress is currently considering a budget proposal that seeks to repeal a lot of those funds and clawback any unobligated money across all IRA-funded initiatives.

“But, as I'm sure you know, the bill still has to pass the Senate and is likely to change (perhaps significantly) before that happens,” Webb said.

An EPA spokesperson said the agency is “reviewing all of its grant programs” to gauge whether they are an “appropriate use of taxpayer dollars” and “align with” the current administration’s policies.

The spokesperson added, “Maybe the Biden-Harris administration shouldn’t have forced their radical agenda of wasteful DEI programs and ‘environmental justice’ preferencing the EPA’s core mission of protecting human health and the environment.”

Jay Benforado, board chair for the Association for Advancing Participatory Sciences, said all signals from the current administration lead him to think that community air monitoring won’t survive.

As for the task force report, Benforado said its recommendations failed to factor in the valuable role that community members, volunteers and academics could play in monitoring air quality.

“I felt the (task force) report…missed the mark somewhat in terms of garnering the full value of community air monitoring,” Benforado said. “Their definition of community air monitoring was how a state government runs community air monitoring. There was less emphasis on engaging the community as equal participants in an air monitoring program.”

Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powers stalling climate action.