ExxonMobil sues, doubling down on advanced plastics recycling

In a new lawsuit, the oil giant alleges the California attorney general and environmental groups defamed the company

The California attorney general and environmental groups defamed ExxonMobil’s integrity and reputation by claiming in lawsuits that, among other things, Exxon’s advanced recycling technology doesn’t work, the oil giant said in a suit filed against those entities earlier this week.

ExxonMobil characterizes the critics’ lawsuits filed in October as a conspiracy and smear campaign. The company is asking a federal court in Texas to make the plaintiffs retract their statements and pay unspecified damages.

“Defendants’ blatant misstatements and attacks on ExxonMobil’s character are targeted at ExxonMobil’s operations in Texas and are actively harming ExxonMobil’s reputation, as well as its contracts with existing and prospective customers,” the company says in the lawsuit filed against California Attorney General Rob Bonta and five environmental groups, including the Sierra Club.

Exxon says California has previously supported advanced recycling, citing 20- and 30-year-old reports from the state about the potential of the technology.

Exxon’s suit also alleges Bonta and the environmental groups are working with the head of an Australian mining company whose charitable foundation has taken aim at the U.S. oil and gas industry. The lawsuit claims the actions stem from the owner’s disappointment at failing to turn the mining company, Fortescue, into a “green energy powerhouse” that would sell hydrogen produced from renewable energy.

While Exxon claims that advanced, or chemical, recycling of plastics works, three of the nation’s 11 advanced recycling facilities closed in 2024, including one that went bankrupt.

“Chemical recycling hasn’t succeeded at scale because the financial and technical obstacles are just too big,” said Jenny Gitlitz, director of solutions to plastic pollution at the watchdog group Beyond Plastics and co-author of the Dangerous Deception report about advanced recycling.

Gitlitz said one technical obstacle is that advanced recycling facilities have to handle up to 16,000 different plastic additives. Exxon’s advanced recycling facility uses pyrolysis, a process similar to incineration, to break down the plastics.

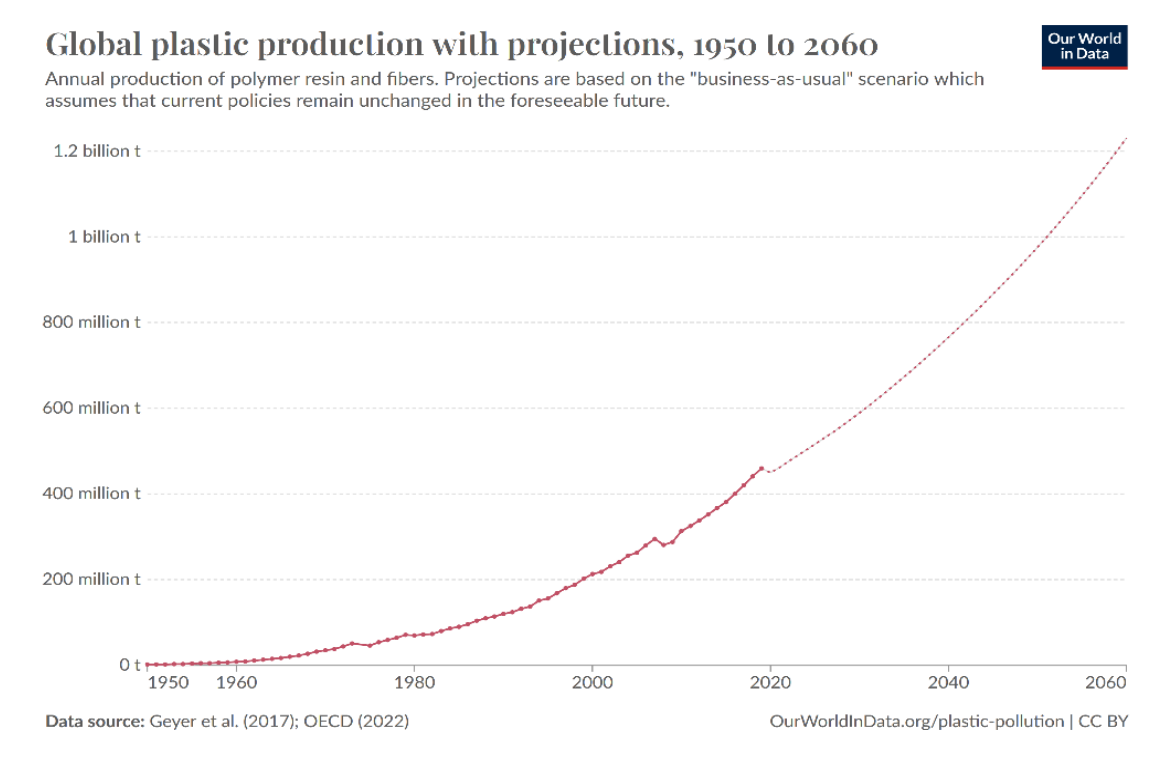

The production of plastics, which are made from fossil fuels, is expected to double or triple by 2050 and could use up to 31% of the remaining global carbon budget for limiting global warming to 1.5°C, according to a study by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

The California attorney general’s suit claims ExxonMobil’s development of advanced recycling is a “public relations stunt without any prospect of meaningfully reducing the amounts of plastic waste or virgin plastic ExxonMobil produces.”

Fewer than 6% of plastics are recycled in the United States. The California lawsuit says 92% of the plastics “recycled” by ExxonMobil at its Baytown, Texas, refinery become fuel. And plastics produced there contain less than 1% recycled plastic, the lawsuit claims.

Exxon says in its suit that it recycled 70 million pounds of plastics at the facility in 2024. In August, a joint investigation by Inside Climate News and CBS News found that more than a year and a half after Houston began collecting consumer plastics for the Baytown plant, it had not started processing those plastics.

In November, the company committed $200 million to expand the Baytown recycling facility to handle 500 million tons of plastics by 2027. Exxon produced 31.9 billion pounds of plastic in 2023, according to Bonta’s lawsuit.

The attorney general and the Sierra Club appeared undaunted by the company’s countersuit.

“Exxon is clearly confused about the difference between defamation and accountability,” Sierra Club spokesperson Jonathon Berman said. “This lawsuit is a shameless attempt at intimidation by a multibillion-dollar polluter corporation that covered up its climate change denial for decades.”

Bonta’s office called the company’s suit “another attempt from ExxonMobil to deflect attention from its own unlawful deception.”

Three advanced recycling facilities closed in 2024. New Hope in LaPorte, Texas, shuttered after less than a year in operation. Fulcrum BioFuels near Reno, Nevada, closed in May after two years. The company has declared bankruptcy. The goal was to convert municipal solid waste — with up to 20% plastics— into aviation fuel. Agilyx/Regenyx, located in Oregon, which recycled styrofoam, closed in February 2024. Despite their closures, owners of the New Hope and the Agiliyx/Regenex projects deemed them successful pilot projects for larger facilities.

“A full-scale plant can cost $200 to $300 million, and collecting, sorting and cleaning post-consumer waste plastics — with all of their incompatible resin types and chemical additives — is also prohibitively expensive,” Gitlitz said.

She added that the plants, predominantly located in communities already overburdened by pollution, produce hazardous waste and generate dangerous emissions and climate-damaging greenhouse gasses. “Reducing plastic production and consumption is our only way out of the plastic pollution crisis,” she said.

Efforts to do that faltered late last year after the 170 attending countries at the United Nations-sponsored Plastic Treaty talks in South Korea failed to agree on curbing the use and manufacturing of plastics. In calling for a binding international pact, the UN Secretary General noted that hundreds of millions of tons of plastics are discarded each year, polluting land and waterways. And microplastics are now commonly found in our bloodstreams.

Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.