Flooding and droughts drove them from their homes. Now they’re seeking a safe haven in New York

Data analysis found higher than average migration growth to the US from areas in Guatemala, Bangladesh and Senegal hit by repeated climate disasters.

This article was produced in partnership between Columbia Journalism Investigations and Documented. It was co-published by The Guardian and republished by Floodlight.

Gricelda experienced her deciding moment in 2018, when she chose to leave the country where she was born after years of not being able to stop the stormwater from seeping into her mud-wall home in the western highlands near the city of Quetzaltenango, Guatemala. Drought only added to her difficulties.

Hossain, two continents away, knew that the changing climate was weighing on his life in the late summer of 2022, when he couldn’t afford to pay the hospital bill to bring his wife and newborn daughter home. His savings were gutted after enduring a decade of frequent flooding that destroyed harvests in the southeastern city of Feni, Bangladesh.

For Mohamed, his reckoning occurred more recently in 2023, after yet another cycle of withering dryness and torrential rain in Diourbel, Senegal, sparked tensions between him and his extended family.

These were the disasters, some sudden, some slow moving, that finally pushed each climate-strafed person over the edge, forcing each to consider what they would come to see as the best remedy for disaster: crossing the U.S.-Mexico border and seeking out a new life in New York City.

Global temperatures have risen steadily, bringing extreme heat, water and food scarcity, and a surge in climate-driven disasters. Since the late 19th century, the planet’s average surface temperature has moved upwards about 2 °F, fueling more frequent and severe storms, floods and droughts that lead to greater deaths and displacements. This human-caused warming is making the middle of the globe, in particular, less habitable than at any time in human history, research shows.

“Eventually, if constraints are not addressed, no further adaptation measures are implemented, and climate hazards intensify, the area could become uninhabitable,” the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, warned in a recent report, referring to coastal communities in the tropical and subtropical regions.

In countries like Guatemala, Bangladesh and Senegal, migrants are fleeing places where storms, floods or droughts have piled on, again and again, since 2010. These extreme weather events have strained fragile economies, pushing people to a breaking point. Few migrants blame the warming planet for their plight. But its impact manifests in their collapsed houses and failed crops. Already, climate-related disruption has become a quiet, yet consistent driver of migration to the U.S.

By 2050, climate change could force as many as 143 million people in the global south from their homes, with hotspots in Latin America, South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Governments, aid organizations and researchers have warned about the climate migration crisis, but it isn’t a far-off threat. It’s happening around the world, and it has reached New York City.

A year-long investigation by Columbia Journalism Investigations (CJI) and Documented found a pattern that spans the globe: Tens of thousands of migrants who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border in 2024 have come from localities repeatedly hit by hurricanes, floods and droughts, according to an analysis of federal data on southwest border apprehensions and international data on major natural disasters.

To understand how climate change may have influenced migrants’ journeys, CJI and Documented analyzed more than nine million records of people apprehended by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) from 2010 to 2024 that included information on the cities, towns and municipalities where they were born. The CBP data was obtained through public-records requests by researchers at The University of Virginia and CJI.

In 2024 alone, CJI and Documented identified more than 520 distinct birth places in Guatemala, close to 350 in Senegal and around 100 in Bangladesh. An analysis of the data shows that around 55 countries that saw higher than average migration rates also were devastated by three or more climate catastrophes from 2019 to 2024, according to the international disaster database known as EM-DAT, which tracks major events reported by UN specialized agencies and other official sources.

The data has gaps. It cannot say why a person left, and it doesn't account for gradual, long-term shifts in weather patterns like excessive heat, diminishing rainfall and sea level rise that may be less dramatic than major disasters but nonetheless have profound impacts. But CJI and Documented used the data as a guide to find migrants affected by climate catastrophes who fled their home countries.

The list includes cities and towns like Quetzaltenango, Feni and Diourbel — places that recent migrants left to build new communities in New York. CJI and Documented interviewed scores of migrants — in cafes, food pantries and other gathering places throughout the city — who say they moved here to escape the worsening effects of hurricanes, floods and droughts back home. Most are among the more than 237,000 migrants and asylum seekers that have arrived in New York City since April 2022, putting pressure on the local shelter system and prompting the use of hotels and large tents as emergency housing.

After arriving, the migrants spread across the five boroughs, often ending up in enclaves established by immigrants from their home countries. Guatemalans, now one of the city’s largest Central American migrant groups, left the country’s western and northern highlands, where repeated storms and prolonged droughts have destroyed livelihoods.

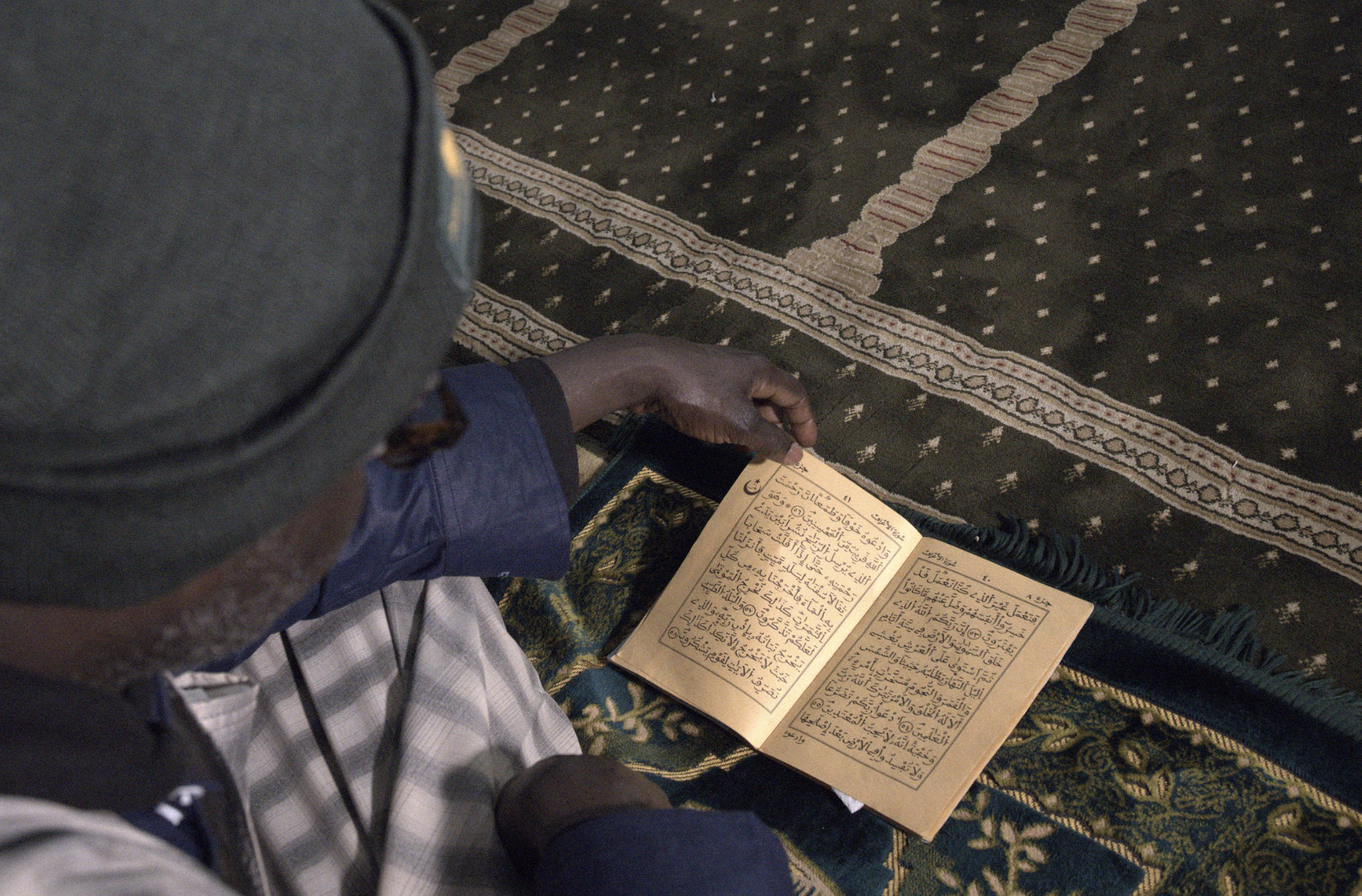

Left: In the Bronx, migrants from Senegal gather to pray in neighborhood mosques, where they form strong bonds with others who have experienced similar climate impacts at home. | Right: This is the backyard of Imam Niass’ mosque where migrants gather. As President Donald Trump rolls out increased immigration arrests, detentions and deportations, migrants displaced by hurricanes, floods and droughts are at risk of being sent back to places hollowed out by climate change. (Jazzmin Jiwa for Documented and CJI)

In the Bronx, migrants from Senegal gather to pray in neighborhood mosques, where they form strong bonds with others who have experienced similar climate impacts at home. Most are from their country’s western region, where rising temperatures and decreasing rainfall have made farming one of the region’s staple crops — peanuts — nearly impossible. From Asia, Bangladeshi migrants, primarily clustered around the desi grocery stores and restaurants of Brooklyn’s Kensington neighborhood, have hailed from coastal areas where monsoon rains cause the Brahmaputra, Ganges and Meghna Rivers to flood.

There is rarely a single, simple cause behind an individual’s decision to migrate, but understanding how natural disasters exacerbated by climate change can push people to leave their home countries is “absolutely important,” said Felipe Navarro, associate director of policy and advocacy for the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies at the University of California’s College of the Law.

"It's not simply that a hurricane happened,” Navarro said. “It's that the hurricane caused devastation, and how the state responded.”

Many who flocked to the U.S. southwest border in recent years have come hoping to seek asylum in this country. But there is no clear category for protection of those fleeing climate disasters, leaving them in immigration limbo.

Now, as President Donald Trump rolls out increased immigration arrests, detentions and deportations, migrants displaced by hurricanes, floods and droughts are at risk of being sent back to places hollowed out by climate change.

Here are their stories.

Quetzaltenango, Guatemala

Gricelda remembers the stormwater seeping through cracks in the walls of her family’s home, leaking through the kitchen ceiling. The house — like some located on the outskirts of Quetzaltenango, Guatemala’s second-largest city — was built from packed mud. Its earthen walls opened up into holes, unable to withstand the rain during Tropical Storm Agatha in May 2010, the first of what would become seven total cyclones, floods and hurricanes over the ensuing years.

“There was a lot of flooding,” said Gricelda, sitting in an empty café in East Harlem and discussing the incident in Spanish. “The rain was very, very heavy.” (Some interviewees requested only to be identified by their first names because of their immigration status.)

Throughout her childhood, Gricelda’s life revolved around her family’s harvest: corn, beans, potatoes, apples. In her village, there were clear signs the growing cycle was changing: the beginning of the rainy season was constantly shifting, and when it did come, the rain fell hard — like Agatha, which inundated fields and obliterated crops. These shocks, paired with recurring droughts that left cropland parched, diminished family harvests.

If the rain arrives too late, a family’s harvest may not grow as it normally would, said Gricelda, whose relatives still live in her native village. “Maybe it won’t yield 100 percent, it will yield 50 percent,” she said. “And because the season is over, it's already a loss for the year.”

What Gricelda witnessed on the ground mirrors what climate researchers have tracked across Central America, especially in Guatemala. Climate disasters have played a major role in driving people north to the U.S.-Mexico border. According to a study by Sarah Bermeo, who helps direct Duke University’s program on climate, resilience and mobility, climate change is intensifying droughts and storms — a dangerous mix for families who depend on the land.

While some families might have the resources to leave their countries and migrate elsewhere, others stay and can become “trapped,” Bermeo said. Her research found a significant spike in families migrating from rural areas in Central America to the U.S. when drought hit the region in 2018. A more recent study tied intense drought during growing seasons in rural Mexico to higher rates of undocumented migration, and it found that the severe conditions discouraged people from returning home.

As a young adult in Guatemala, Gricelda noticed the drought was getting worse. Some days the only way to get water was by truck. Other days Gricelda had to trek down to the river to collect her own. “There wasn’t much rain anymore, and when storms hit, they left the river dirty,” she said. “It became harder just to have clean water.”

Hurricanes and heavy rains punctuated the drought and swept through the village, destroying homes and disrupting the harvests. Gricelda remembers rain repeatedly soaking through the walls in her in-laws' mud house. As the dry spells stretched longer and the rains poured down harder, sustaining the family’s livelihood became difficult.

Around 2013, after multiple flooding incidents, Gricelda’s husband decided to leave for New York City, where he worked in restaurants cooking and cleaning. She stayed behind with her two children, watching as her in-laws’ house grew weaker with each storm. By May 2018, torrential rains had inundated swathes of Guatemala, including Quetzaltenango. Subsequent floods damaged roads and interrupted essential services for 5,500 people.

With no clear future in her country, Gricelda finally made a choice: she took out a loan, using her father’s land as collateral. With the help of a smuggler, she led her children on a three-week trek to the U.S.-Mexico border. Arriving in Texas, federal agents asked for her children’s birth certificates and escorted the family to an immigration shelter. Her husband eventually bought them bus tickets to New York.

Two years later, in November 2020, Hurricanes Eta and Iota touched down on Guatemala, battering houses and swamping farmland already strained by years of storms. In the country’s western highlands, communities like Quetzaltenango have seen rising numbers of families leave for the U.S. in recent years — not always after a single climate catastrophe, but rather after years of accumulated stress. While migration from Guatemala has decreased overall, the share of migrants coming from this region has grown slightly between 2019 and 2024, the analysis by CJI and Documented shows.

Seven years have passed since Gricelda arrived in New York City. She now raises her four children in a two-bedroom apartment in East Harlem and works for Red de Pueblos Transnacionales, a local organization that launched the city’s first collective of Indigenous-language interpreters, “the Colectivo Colibrí,” or hummingbird, which offers translation services to Central American immigrants. Gricelda informs other Latin migrants how to find resources in the city.

She tried to apply for asylum once, she said, but her lawyer defrauded her of more than $10,000. She has yet to trust the system enough to try again.

Today, she has nothing but a red card given to her by her employer, which details instructions on how to respond if she encounters U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents.

“I don’t want to go back,” Gricelda said.

Feni, Bangladesh

Hossain’s wife, Shumaiya, had just given birth to a baby girl in September 2022. The couple hoped it would be a new beginning — they lost a child four years earlier. But when Hossain picked up his wife and newborn daughter from the hospital in Feni, Bangladesh, he got a $470 bill for the C-section. He couldn’t afford it.

Floods had battered the couple’s house and surrounding rice fields five times over a decade, and not being able to harvest crops had drained their income. They had to scrape together money from relatives and a friend in order for Hossain to bring his new baby home.

Like others in this mostly rural southeastern region where three rivers meet, Hossain made money growing rice on his land and selling it at a local market. But every flood waterlogged his fields for months at a time. For several years, he only managed to farm about a third of his land — less than the size of a soccer field. He struggled to pay for his family’s food and health care.

Many of Feni’s 1.6 million residents work on or own farms.Others are fishermen or make crafts from jute and ceramics. Over the past 10 years, floods have killed nearly 300 people in Feni and nearby regions, the EM-DAT disaster data shows. Rising sea levels caused by climate change have worsened flooding in the last two decades, said Sanzida Murshed, a geographer and disaster scientist at the University of Dhaka, in Bangladesh’s capital.

This has reduced food production in coastal areas like Feni, Murshed said. Because floodwaters have nowhere to drain, the soil has become increasingly saline, making it harder to grow rice.

More Bangladeshis from these same areas have migrated to the U.S. southern border than from the country overall, CJI and Documented’s analysis shows. Noakhali — located around 30 miles from Feni — tops the list of origin cities for Bangladeshi migrants, accounting for more than 30% of recorded Bangladeshi cases with documented locations in the border apprehensions dataset.

As is usually the case for people hit by natural disasters, the first move for many families in Feni was to the country’s capital, where the cost of living is much higher. Chowdhury stayed behind and, wanting change in his homeland, got involved in opposition politics. As a result, he said, he received threats from local ruling party members. Meanwhile, the floods continued to destroy his crops. The combination of factors pushed him to leave, he said.

“I was always really tense. I wasn’t able to function,” said Hossain, who heard about others getting asylum in this country. A friend recommended that he go to Brooklyn because of its large Bangladeshi community.

Hossain Chowdhury sits in his room in Brooklyn, left, and at right, looks at photos of his family. In February 2023, he left Bangladesh, traveling through 11 countries by air and road for nine months to reach the United States. (Jazzmin Jiwa for Documented and CJI)

Hossain sold his land and borrowed roughly $33,000 from relatives and friends to raise $41,000 to pay for travel and smuggling fees to the U.S. In February 2023, he left Bangladesh, traveling through 11 countries by air and road for nine months. He handed himself over to border officials in Arizona, who held him in a cell with 15 people for three days. After his release, he flew to New York City, where an estimated 100,000 Bangladeshi people live.

By then, migrants from around the world had flocked to the border in the hopes of getting released, often to pursue claims for relief in immigration court.

From 2019 to 2024, border crossings from Bangladesh increased by 150%, with Feni — located in the disaster-prone Chattogram region (formerly known as Chittagong) — ranking among the top 10 Bangladeshi cities with the highest number of people who arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border, CJI and Documented’s analysis shows.

According to a recent survey conducted by a New York City community organization, Desis Rising Up and Moving (DRUM), climate disasters have pushed 135 recently arrived Bangladeshi and other migrants from their countries.

In April 2024, a Manhattan law firm filed a political asylum case for Hossain based on his support for Bangladesh’s political opposition party, documents show. The impact of the worsening floods on his income and his livelihood is not recognized as a reason for claiming asylum.

Seven months later, while waiting for his claim to be heard in the backlogged immigration court system, Hossain got a work permit. He landed a job as a kitchen helper in a local restaurant, then a food delivery worker biking around Brooklyn. Now he works full time in a Bengali sweet shop and café in Kensington, Brooklyn's Little Bangladesh. He lives nearby in a basement apartment with two roommates, and works six days a week — seven during religious festivals.

Last year, one of the worst floods in over three decades hit his hometown of Feni, where his wife and daughter still lived. This one submerged the family’s house under three feet of water, deluging it with sewage, snakes and frogs. Flooding damaged nearly every item in his home — three beds, a sofa, chairs. His wife and daughter had to move to a relative’s house roughly 100 miles away in Dhaka.

Hossain hoped to get asylum and apply for his wife and daughter to join him. If he knew about the challenges of making that happen today, he said, he wouldn’t have come to the U.S. Now that he’s lost what he had in Feni, he estimates it would cost up to $45,000 to build a new house there.

Threats of deportation have shaken Brooklyn’s Bangladeshi community. When ICE agents detained two Bangladeshis from Noakhali who were working in Buffalo, New York, word spread to Kensington. Not long ago, the neighborhood’s Noakhali Deshi Bazar bustled with families buying groceries. Men packed themselves into eateries like Raj Mahal Restaurant + Sweets. Today, its streets have gone quiet.

Hossain's belief that he could find safety here has dissipated. “I live in terror,” he said. He keeps a copy of his asylum application and notices of court hearings in a plastic folder in a bedroom drawer. His lawyer is on speed dial in case ICE agents come to the door.

“If I was forced to go back, I do not know how I would feed my family,” Hossain said. “Now I have lost my home in the floods. I have nothing to go back to.”

Diourbel, Senegal

Mohamed sat cross-legged on the carpet before a Friday afternoon prayer at a mosque in the South Bronx, remembering his crops with fondness. He grew maize, watermelon and peanuts on a family farm in Diourbel, Senegal, and worked as a seasonal laborer on another farm about 40 miles away in Kaolack.

Some 40 West African immigrants, many who arrived in New York in recent years from Senegal, sat next to him. A show of hands indicated about a third of them were farmers who had experienced floods and droughts. Many fell victim to the same cycle of climate events that would impact Gricelda and her family 5,000 miles away in Guatemala.

“When it rained, everyone was caught off guard because for a very long time we didn’t have any rainfall, there was drought,” said Mohamed, 45, who inherited land from his grandfather in 2005.

For more than a decade, Diourbel, Kaolack and neighboring places had faced recurring cycles of flooding and drought. Yet migration from Senegal’s western and central regions to the U.S. surged after more than a half dozen major floods had occurred in 2020, CJI and Documented’s analysis shows. Between 2019 and 2024 — following years of accumulating climate events — more than 1,800 Senegalese migrants from these regions crossed the U.S.-Mexico border — a sharp rise from virtually none.

When flooding hit Mohamed’s hometown of Diourbel, water pooled on the land, sitting there for months, turning green and mosquito-ridden. His family couldn’t spend time outside. Mohamed had to build a brick path so his wife and children could enter their home.

He decided to switch from the area’s traditional crop of peanuts to maize. Without in-depth knowledge of the changing climate, Mohamed thought that, since maize grows between 5- and 12-feet tall, it might survive the harsher conditions. But each of the stalks eventually withered and died. “The land was basically useless,” he said.

Eventually, the torrential rain and prolonged dryness deepened tensions among his relatives, who were living in separate houses on the family compound. Mohamed’s brother, who earned more money as a teacher, constructed a new house with a six-foot foundation made of sand, gravel and cement. When it flooded, the water wouldn’t enter his home. Yet Mohamed would have to scramble to dump buckets full of water out of his house and use towels to mop up.

His six children, ranging from two to 13, got bullied about their dilapidated house. Taunts and jeers followed the family at school, work and home, leaving them feeling alienated.

Dina Esposito, who ran a global resilience and food security program for the U.S. government from September 2022 to January 2025, said pressure caused by climate change can exacerbate conflict. “Inter family or inter community conflict comes about when climate stresses create economic strain,” she said.

When Mohamed watched scenes of New York’s Times Square on television in his Diourbel home, he admired the flashing lights and supersized digital screens.

Videos on TikTok and Instagram, often made by smugglers posing as travel agents, promoted what seemed like comfortable journeys. Speaking Wolof, the predominant language of the Senegal region, they told viewers it was easy to get work permits and jobs in the U.S.

Mohamed saw the reels about how migrants had entered the U.S. by traveling through Nicaragua. A friend introduced him to a smuggler who was advertising to help people get visas and airline tickets, and connect them with other smugglers along the way. “I was told that once I get to the U.S., ‘Everyone is equal before the law. Nobody can deport you,’ ” Mohamed said.

By October 2023, he had sold a horse, some cows and a cart for about $4,500 and borrowed money from relatives to pay more than $10,000 to travel to this country. He turned himself in to border patrol agents in Arizona, who detained him overnight before releasing him.

In New York City, he found a different world than the flashy videos he’d seen.

He stayed at a migrant shelter near Times Square, where he tried to navigate the U.S. asylum system. But he didn’t know his encounters with droughts and floods would mean little for his asylum claim, he said, and mentioned the climate disasters that had diminished his livelihood in his application.

Commuting between the immigration office and the shelter, Mohamed rarely took in glittering scenes. Instead, he saw homeless people begging for help behind signs saying they had lost hope. “The more time I spent here, the more I realized the reality is different,” he said.

Within a month, Mohamed said, the shelter evicted him after another migrant had complained that he entered the female bathroom. He had mistakenly entered the bathroom because he couldn’t read the sign, he said. A shelter spokesperson declined to comment.

Mohamed resorted to sleeping on the 2 train, where he met other Senegalese people. Many had headed for New York City with contact numbers for imams who lead mosques here, much like their grandfathers did in Senegal. They suggested he seek help at the Bronx mosque. There, he made friends with other struggling farmers from Diourbel and Kaolack.

“We would talk about how our family members are anticipating the rainfall and the flooding that comes with it,” said Mohamed, who found solace sitting on a prayer mat reading verses from the Quran. It reminded him of his father, a religious teacher.

One new friend, Omar, a delivery driver, brought food to the mosque to share with him. Another, Ndiaga, waited with him outside a nearby Home Depot, anticipating passersby offering odd jobs.

In the months since about a half dozen local WhatsApp groups have emerged, connecting thousands of migrants from West Africa who have settled here. The chats have functioned as support groups of sorts. Members circulate information about jobs and rooms for rent. Some have offered their brethren more. The Bronx mosque’s leader, Imam Cheikh Tidiane Ndao, hails from Kaolack, where his grandfather was a well-known religious figure. He said he’s conducted 40 marriage ceremonies for migrants who met through his mosque’s burgeoning community.

Recently, the community has focused on the Trump administration’s deportation threats. In voice notes on one WhatsApp group, which the imam shared with CJI and Documented, a migrant who had left immigration court warned that officials were giving migrants just two weeks to present all their documentation, before deciding whether they could stay in the country.

News of the threats has yet to make its way back to Senegal. Imam Ndao said he continues to receive more than 10 phone calls a month from farmers there, asking for help. Often, they tell him they can only afford to eat one meal a day. They’re allured by the promise of making more money in a week in the U.S. than they can in months in Senegal.

“They still want to come to America,” the imam said.

Malick Gai and Subhanjana Das contributed reporting and translation services for this story. Fabien Cottier, a political scientist at Columbia University and the University of Geneva, contributed to the data analysis.

Jazzmin Jiwa and Carla Mandiola reported this story as fellows for Columbia Journalism Investigations, an investigative reporting unit at the Columbia Journalism School.

How we found migrants affected by climate-driven disasters

To understand how climate change may be influencing irregular migration to the United States, Columbia Journalism Investigations (CJI) and Documented spent nearly a year analyzing more than nine million records of people apprehended by the U.S. Border Patrol from 2010 to 2024 under U.S. Code Title 8, a classification of U.S.-Mexico border encounters. The federal Customs and Border Protection (CBP) dataset, obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests by researchers at the University of Virginia and CJI, included the reported birthplace of each person apprehended, and represents the most detailed source available on where border crossers were born down to the locality, including city and town names as well as states, departments and municipalities...