A fossil fuel group is working with US tribes to boost LNG exports

Liquefied natural gas exports are among the worst fossil fuels for the planet, according to a new peer-reviewed study

Published by ICT News, Source New Mexico

In the Navajo Nation, and for many tribes, sage is a sacred plant burned in ceremonies to promote healing, spiritual protection and connection to the land. But Meredith Benally, who is Diné and the co-director of the environmental group C 4 Ever Green, has noticed the plant is becoming scarce due to climate change, pollution and other stressors.

For more than 60 years, the tribe has hosted oil and gas fields that have contaminated the surrounding land, water and air in the Four Corners region of Arizona, Utah, New Mexico and Colorado. Residents believe the oil and gas wells are contributing to health issues like asthma, and leaks of hydrogen sulfide gas have caused vomiting in children.

The wells are also contaminating the sage, said Benally, who lives on the reservation, south of Bluff, Utah. “All the burn off from the oil that they’re extracting, it gets all over the plant. When we use it, we're ingesting all of that.”

Benally believes fossil fuels harm their culture. “It not just affects us physically and spiritually, but it also affects us mentally, because we have such a strong relationship with the land.”

The climate crisis is threatening Indigenous communities in the western United States with drought and extreme heat — while many tribal homes lack clean water and electricity for cooling. The crisis is made worse by oil and gas wells that guzzle scarce groundwater and emit harmful pollution.

At a time when the United States must move away from fossil fuels to save the planet, three western tribes, three states — New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming — and the Mexican state of Baja California, have signed agreements with an industry group promoting long-term contracts to export gas to Asian markets. The effort could bring revenue to tribes but also exacerbate climate change, which is having devastating impacts on communities in the West.

The group, Western States and Tribal Nations Natural Gas Initiative (WSTN), describes itself as a unique collaboration between tribes and state governments. Its goal of increasing drilling of natural gas in the West for export to Asia is endorsed by the Biden Administration led by Rahm Emanuel, a former top aide to President Barack Obama and now ambassador to Japan. It will likely be supported by incoming President Donald Trump’s administration.

The gas, which is primarily composed of planet-warming methane, would be super-cooled and compressed for export as liquefied natural gas (LNG) from facilities on Mexico’s west coast.

The gas primarily comes from a hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, boom in the United States, including on tribal lands in the West. Fracking involves injecting huge amounts of water, chemicals and sand into the ground to unlock previously inaccessible gas.

The group claims that it is reducing global emissions by helping countries to replace coal with methane. But new peer-reviewed research found that greenhouse gas emissions from American LNG exports can be 33% worse than coal.

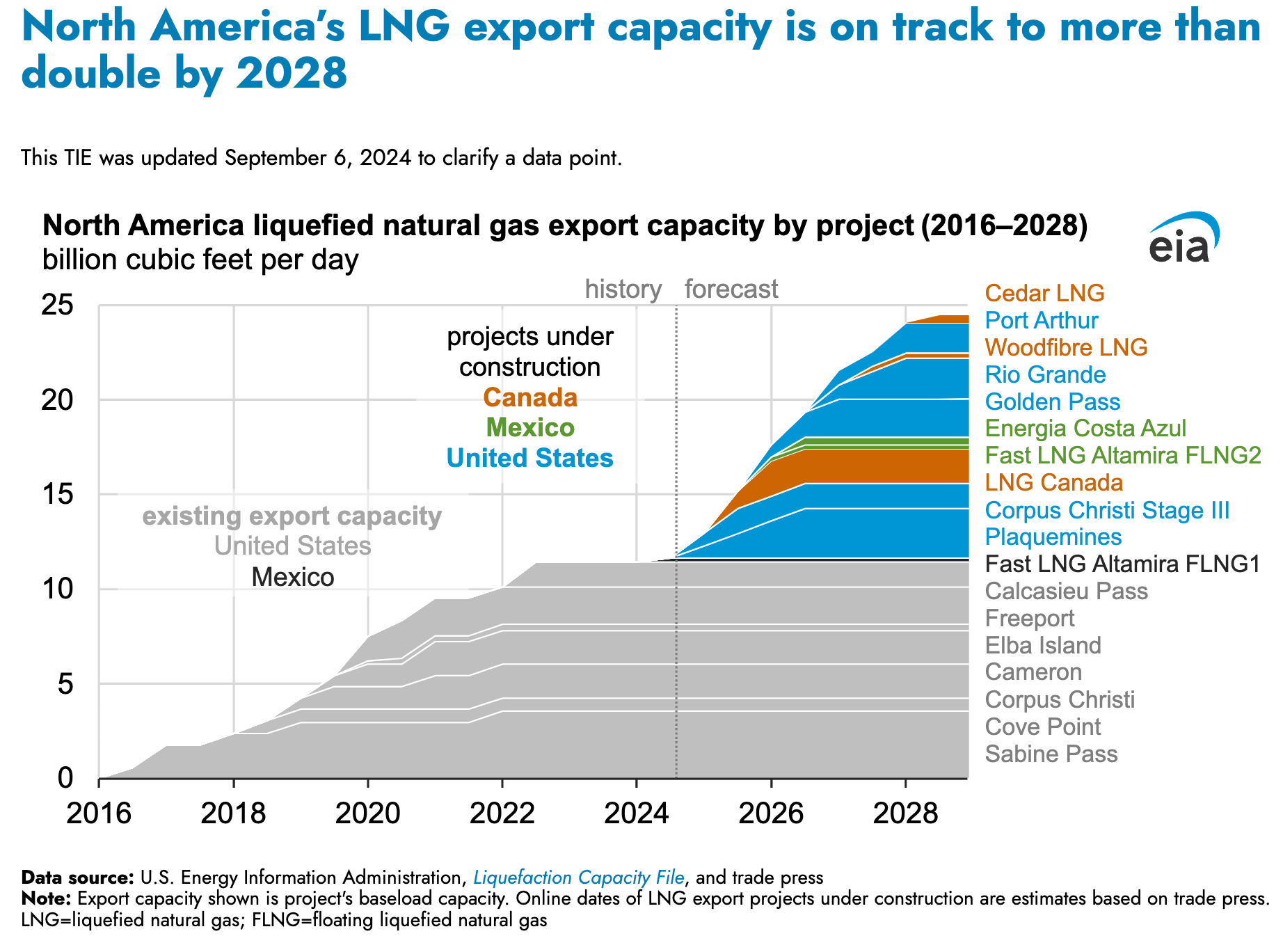

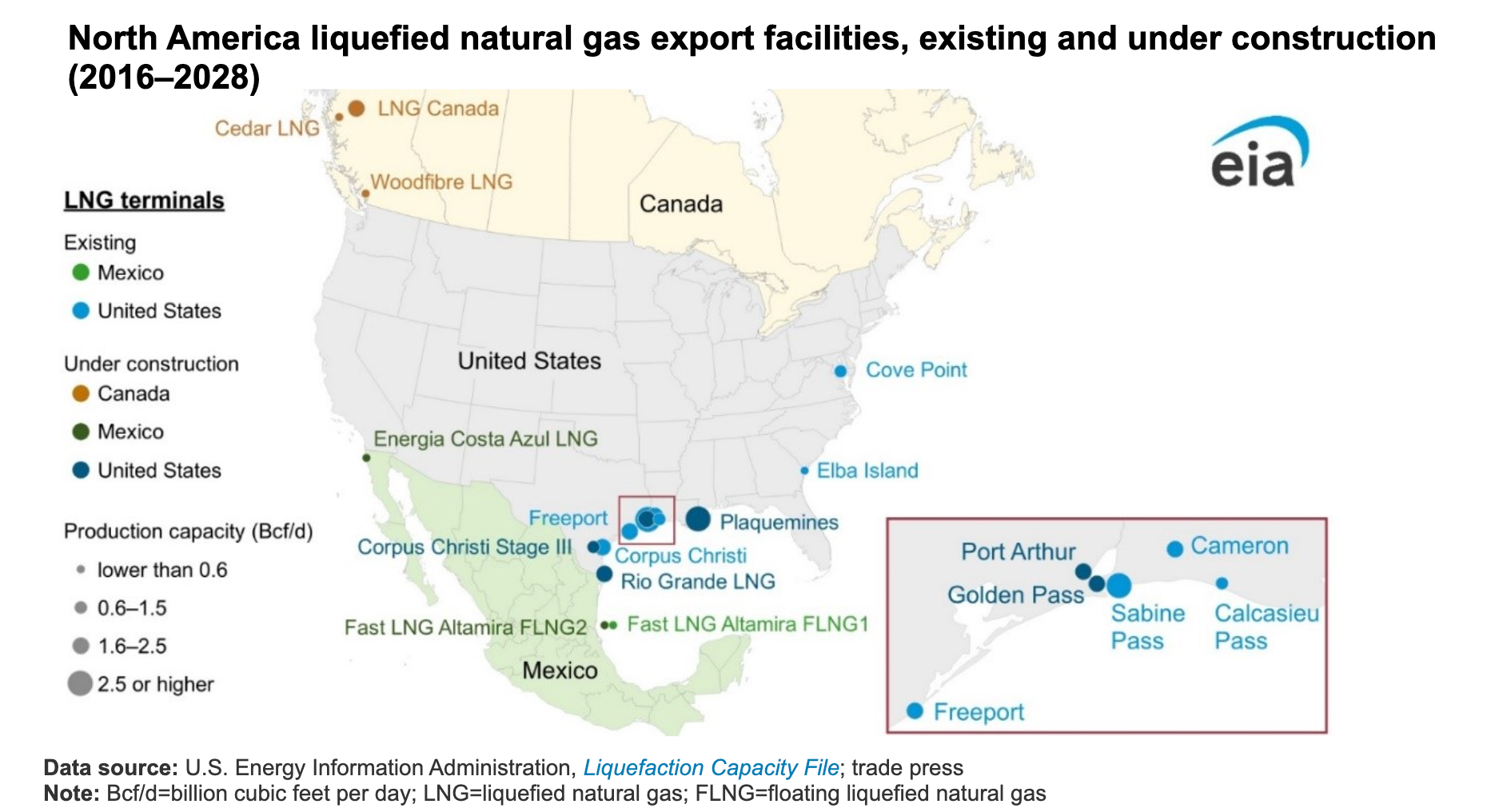

WSTN is part of a larger push for LNG expansion in North America. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the continent’s LNG export capacity — already the largest in the world — is on track to more than double by 2028. That includes LNG export terminals in Mexico that WSTN is backing.

The group plans to build new pipelines to the west coast of Mexico. “Permitting for new build construction could take two to three years,” it said in a 2022 presentation. “Tribal Nations’ input (is) crucial and tactical in cutting lead time to construction.”

WSTN has signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the Ute Tribe in Utah, Jicarilla Apache Nation in New Mexico and Southern Ute Indian Tribe in Colorado. A 2023 document obtained by the Energy and Policy Institute said the group was “currently courting” the largest tribe in the United States, the Navajo Nation.

Navajo Nation leadership appeared on a panel as part of a pro-LNG event organized by WSTN. The group also suggested in documents that it could use bonds to underwrite infrastructure — including through the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority.

The group met with Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren in late 2023, and there has been no further dialogue, according to the tribe’s public relations director George Hardeen. “WSTN had an introductory meeting with President Nygren and nothing more,” said WSTN Vice President Bryson Hull.

Benally believes fossil fuels should remain in the ground. “They should stay in (their) natural state.”

Who is behind Western States and Tribal Nations?

The group began as an effort by the Colorado and Utah state energy offices to develop their gas markets. Later, tribes were invited to join by signing an MOU. The state of Colorado is not a member, but several counties in the state have joined.

In 2019, the fossil fuel advocacy group Consumer Energy Alliance (CEA) wrote a report that laid out a path for exporting gas from western states to Asian markets via the U.S. West Coast.

The report zeroed in on the proposed Jordan Cove LNG facility in Oregon as the “most promising” option, although it faced broad opposition from the public and tribes in the area.

One of WSTN’s funders at the time was Pembina Pipeline Corp., the company behind Jordan Cove. WSTN began advocating for Jordan Cove, taking out an ad in the local paper that claimed the LNG facility would create jobs, support tribal economies and help the environment.

The ad caught the attention of local Oregonians, who wrote a research paper that found WSTN was closely linked to CEA and consulting firm HBW Resources. They wrote that CEA and HBW have a history of promoting the fossil fuel industry by creating regional campaigns “that are made to appear to have sprung from the grass roots.”

Hull said WSTN is not an industry front group but is an organization led by a board of directors appointed by democratically elected state and tribal governments. “The researchers in question were on the opposite side of WSTN regarding Jordan Cove and were therefore biased,” he wrote in an email.

When Jordan Cove died in 2021, the group quickly pivoted to another opportunity to export western gas — Sempra Energy’s LNG facilities on Mexico’s west coast. The company owns infrastructure and utilities across Southern California and Texas, and secured export licenses from the U.S. Department of Energy for its Mexico facilities.

Hull said the majority of the group’s funding comes from tribal, state and county governments. However, companies can join the group by paying an annual membership fee, as Sempra did in 2020 by paying a fee of $20,000, according to a record obtained by the Energy and Policy Institute.

In August 2022, a WSTN delegation visited Sempra’s Energia Costa Azul facility in Mexico — “an excellent opportunity” to see its potential for western gas and LNG exports, wrote founder and CEO of WSTN Andrew Browning in an email obtained by the Energy and Policy Institute. He wrote that the trip would set the stage for a summit planned for later that year.

In December 2022, WSTN held a two-day event in Colorado. The event was sponsored by Sempra LNG and featured a presentation by the company about its Mexico facility.

The event included potential overseas customers. Ambassador Emanuel and Takeshi Soda, the director of Japan’s Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry oil and gas division, both spoke at the event. According to a WSTN email sent after the event, Soda told the audience that LNG procurement was in a “state of war.”

Japan became a major buyer of U.S. LNG after the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011 forced it to diversify.

“Japanese utilities have (become) very deeply entrenched into the LNG market, to the point where they're not just buying LNG for use in their own plants, but they are trading LNG into the wider market,” explained Lorne Stockman, research co-director at Oil Change International, a nonprofit dedicated to fighting the fossil fuel industry. “They've contracted a lot more LNG than they need … and (are now) trading that surplus on markets and profiting from that.”

The summit included a panel called “Tribal Perspectives on Resource Development” featuring members of tribes that signed MOUs with the group, along with Navajo Nation Vice President Myron Lizer. According to a WSTN email, the panelists said tribes have energy development interests but are hampered by a “paternal approach” by federal government bureaucracy and “urged immediate reform to layers of red tape.”

Does WSTN represent tribal communities?

Fossil fuels have created both wealth and environmental degradation for some western tribes.

Forrest Cuch, a Ute elder and author of “A History of Utah’s American Indians,” was born in the 1950s, before fossil fuel extraction spread across Ute lands. After college, he returned to the reservation. “When I came back, the oil wells were all over the place, and that continues today,” Cuch said.

Settlers displaced the Ute people to lands that were thought to be less bountiful but in fact contained fossil fuels under the soil. Oil and gas revenues have helped the tribe fund services, pay attorneys to defend their sovereignty and allowed people to pay off their homes and cars.

An environmentalist, Cuch feels torn by the tribe’s relationship to fossil fuels. He has received royalties and benefited from oil and gas-funded tribal services. At the same time, he knows extraction has polluted the air, water and soil. Tribal members have found ulcers in wildlife as a result of water contamination. And the gas flaring contributes to climate change, exacerbating drought and wildfires near Ute lands.

“So it's not a clear black-and-white situation out here. There's always benefits, but also a lot of disadvantages,” said Cuch, adding that he does not speak for the tribal government.

All three tribes that signed an MOU with WSTN were already deeply invested in fossil fuels that fund tribal operations.

The first to join was the Ute Tribe, which primarily funds its government through massive oil and gas production on its lands. It was followed by the Southern Ute Tribe and the Jicarilla Apache Nation, tribes that are largely dependent on oil and gas revenue. Floodlight reached out to all three tribes but did not receive a response.

Historical factors push tribal governments to partner with the fossil fuel industry, said Brenna Two Bears, lead coordinator for the Keep It In the Ground campaign, part of the Indigenous Environmental Network.

Land dispossession and other discriminatory government policies created impoverished conditions on many reservations, said Two Bears, who has roots in the Ho-Chunk, Navajo and Standing Rock tribes. When resources are found on tribal land, there is a history of companies offering benefits in exchange for extraction.

“That creates that environment for oil and gas companies, or other natural resource extractive companies, to come in and say, ‘We can provide you with the things that you don't have,’ ” she said.

Tribal governments signing agreements does not equate to community support, Two Bears said.

“It's really difficult for a lot of communities to be able to have a say in what is happening within their tribe,” she said. “You see something similar in the United States federal government — a lot of what happens isn't coming directly from the people themselves.”

Two Bears said many tribes want to exit the cycle of extraction. “Because of the lands that we've been removed to, and our lack of economic support, it all compounds and creates this awful cycle where we're trying to get out of it, and the only lifeline we get is from these companies, and then we take it, and then it just makes it worse. It keeps going and going,” she said.

In an email, Hull said WSTN “represents neither the people of the sovereign tribal nations nor citizens of the states which have signed the memorandum of understanding that governs WSTN.”

“Those governments are duly and democratically elected, and as such, have the sole right to appoint their representatives to the Board of Directors, which leads WSTN,” he said.

In a 2023 presentation, WSTN said it is “led by sovereign tribal nations, states and counties” and it is “advancing tribal self-determination.”

But Two Bears questioned how the group presents the idea of sovereignty. In her view, sovereignty means the community has the right to reject resource extraction, even if the tribal government supports it.

“At the (Indigenous Environmental Network), we view sovereignty as the right to say no,” she said. “But of course, that disconnect between the communities and the tribal governments can be very wide and very hard to close.”

Dubious emissions claims

WSTN’s central environmental claim is that U.S. liquefied natural gas can be climate-friendly by replacing coal burned overseas.

A study that the group commissioned claims that “LNG produced in Rockies basins and exported from the North American West Coast to China, India, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan would produce net life cycle emissions reductions of between 42% to 55% if used to replace coal-fired energy generation.”

But a leading scientist said this claim is not accurate. “(Fracked) gas going to LNG is probably the worst fossil fuel to be doing in terms of its climate impact,” said Robert Howarth, a Cornell University professor of ecology and environmental biology.

Howarth authored a peer-reviewed study that found LNG exports have a greenhouse gas footprint that’s 33% greater than for coal. He said indirect emissions — those from drilling, fracking, processing, storing and transportation — are enormous for LNG compared to coal. The emissions intensity primarily comes from methane, a potent greenhouse gas that traps 28 times more heat than CO2.

Howarth told Floodlight: “There's no way they accurately captured that and reached the conclusion they did. They’re just plain wrong.”

Stockman, of Oil Change International, agreed with Howarth. He said the claim that LNG could lower emissions by up to 55% is “completely inaccurate.”

Stockman added that the global transition to renewables is well underway, and it’s incorrect to assume that gas will displace coal. “LNG is more likely to displace renewables, electrification and efficiency going forward than it is (to replace) coal,” he said.

Hull called Howarth’s study “highly politicized” and “politically motivated.” Hull defended his group’s study, saying “WSTN commissioned duly credentialed academics to carry out the study, which speaks for itself.”

He also pointed to a 2019 report for the National Energy Technology Laboratory that concluded the use of U.S. LNG exports for power production in Europe and Asian markets will not increase greenhouse gas emissions from a life cycle perspective compared to coal extracted and burned regionally.

One way that the U.S. gas industry seeks to rebrand as “green” is by using certification programs. WSTN sought to create its own “clean” gas certification program through San Juan College in New Mexico.

According to records obtained by Energy and Policy Institute, Sempra LNG supported the effort with a letter that claimed “natural gas from New Mexico will be a critical part of accelerating efforts by buyers in Asian markets to shift their economies away from higher emitting fuels.” Hull wrote in an email to Floodlight that gas “produced with stringent processes” can lower emissions.

But Stockman said America’s LNG industry continues to emit huge amounts of methane.

“Despite this idea of certified gas lofty claims by industry representatives that the U.S. gas industry is cleaning up, and that U.S. LNG will be the cleanest in the world in some distant time in the future — that's just not happening. And the evidence is clear: the U.S. methane emissions from the oil and gas sector are the largest in the world,” he said.

Stockman warned that the earth is close to overshooting the internationally-agreed upon goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. “Any expansion of fossil fuels is undermining our progress towards avoiding complete climate catastrophe,” he said.

Back in the Navajo Nation, it’s unclear how much the community knows about the group’s 2023 meeting with the tribe’s president.

WSTN set its sights on engaging with the Navajo Nation in 2019. Hull said the group’s board of directors, appointed by states and tribal governments, “encourages conversations with other states and sovereign tribal nations.” In response to environmental concerns from community members, Hull wrote, “WSTN respects all opinions.”

If the Navajo Nation wanted to sign an MOU with an industry group, Benally said it would need permission from chapters within the community whose land would be affected. “So it's not just tribal leadership making decisions. It has to be the people themselves.”

Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.