How Big Oil is ruining a small ‘slice of heaven’ town in Texas

Export terminals shipping nearly half of U.S. crude oil have formed around Ingleside on the Bay, turning the coastal town into an unlikely ‘fenceline’ community.

This is a condensed story of a three-part series produced by The Xylom and co-published by Drilled, Floodlight and Deceleration News. Subscribe to The Xylom's newsletter here.

On Jan. 6, 2024, nine minutes before midnight, the police department in Ingleside, Texas, uploaded on Facebook a now-deleted public advisory about an oil leak from a tank at the Flint Hills crude oil export terminal.

The roughly 700 members of Facebook group Citizens of the City of Ingleside on the Bay were in a frenzy. They reported a gaseous odor and burning eyes from the 2,900-barrel on-site oil spill. Town pharmacist Idana Merrick posted that she turned off all fans in her house to keep the fumes from being drawn in.

It was the second time in just over a year that the community had been subjected to a spill from Flint Hills. On Christmas Eve 2022, 335 barrels of crude flowed into Corpus Christi Bay, creating yellow gelatinous globs in the aquamarine water.

Ingleside on the Bay is a small seaside town with 614 residents in San Patricio County, Texas. Residents in this toney enclave have a front-row seat to picturesque Corpus Christi Bay.

Ingleside on the Bay is the opposite of the stereotypical “fenceline” community: over 80% of the town’s residents are white. Many are semi-retired. And unlike poor communities exposed to polluted air, water or land, many residents here have the means to move out.

Almost overnight, this coastal community has become America’s crude oil export capital — a place where residents supported Donald Trump — America’s “drill baby drill” president — by 50 points.

Within a 2-mile radius of Ingleside on the Bay’s City Hall are three massive crude oil export terminals, which send tankers the length of a football field into the Gulf. The facilities are located at and near the site of a decommissioned U.S. Navy installation.

They include Gibson South Texas Gateway, Flint Hills Resources Ingleside Terminal and Enbridge’s Ingleside Energy Center, the largest U.S. crude oil storage and export terminal by volume. Together they account for nearly half of U.S. crude oil exports — an estimated 700 million-plus barrels in 2024.

The crude that passed through the three export terminals in Ingleside on the Bay in 2023 alone was worth roughly $50 billion, or more than the entire GDP of the state of Wyoming, The Xylom estimates.

The price of oil exports

But the economic, health and environmental costs are also high: Local and federal governments have spent nearly half a billion dollars deepening the channel for the massive tankers. A 6-foot-tall pile of dirt from the dredging now blocks the Corpus Christi skyline. And white foamy gunk has started floating on the water. Dead sea turtles have washed ashore.

The Xylom asked students at MIT to look at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency environmental risk indicators around Corpus Christi. They found the score for the county including Ingleside on the Bay increased nearly 17-fold since 2018.

The indicators estimate risk based on “the size of a chemical release, the fate and transport of a chemical within the environment, the size and location(s) of potentially exposed populations and a chemical’s relative toxicity.”

Suzi Wilder, an RV park owner and Ingleside on the Bay City Council member, recalls that when the largest terminal run by Enbridge came to town, “All hell breaks loose.”

“Ingleside on the Bay is our slice of heaven that you’re willing to turn into hell for a profit,” said Kelley Burnett, who captains the local dolphin boat tours. “This is not just about our health, but our livelihood.”

Troubled by what they could see, and even more so by what they thought they couldn’t, the local Coastal Watch Association contacted Earthworks, a national nonprofit that aims to prevent the destructive impacts of energy extraction.

Using special cameras that observe chemicals normally invisible to the naked eye, Earthworks found several volatile organic compounds — which can cause respiratory system irritation, nervous system damage and even cancer — leaking out from Flint Hills Ingleside.

Lynne Porter, a retired assistant superintendent of the Ingleside School District, moved in three years ago. Porter, a board member for the Coastal Watch Association, says she now requires an inhaler to get through her day.

“That’s the thing with this industry,” concludes Wilder. “They’re not out to protect this town.”

Enbridge and Gibson declined comment. In an emailed statement, Flint Hills, which was fined nearly $1 million for its spill, responded that it “has worked cooperatively with state and federal agencies to resolve all matters related to a release of crude oil … in December 2022.”

US starts shipping oil overseas

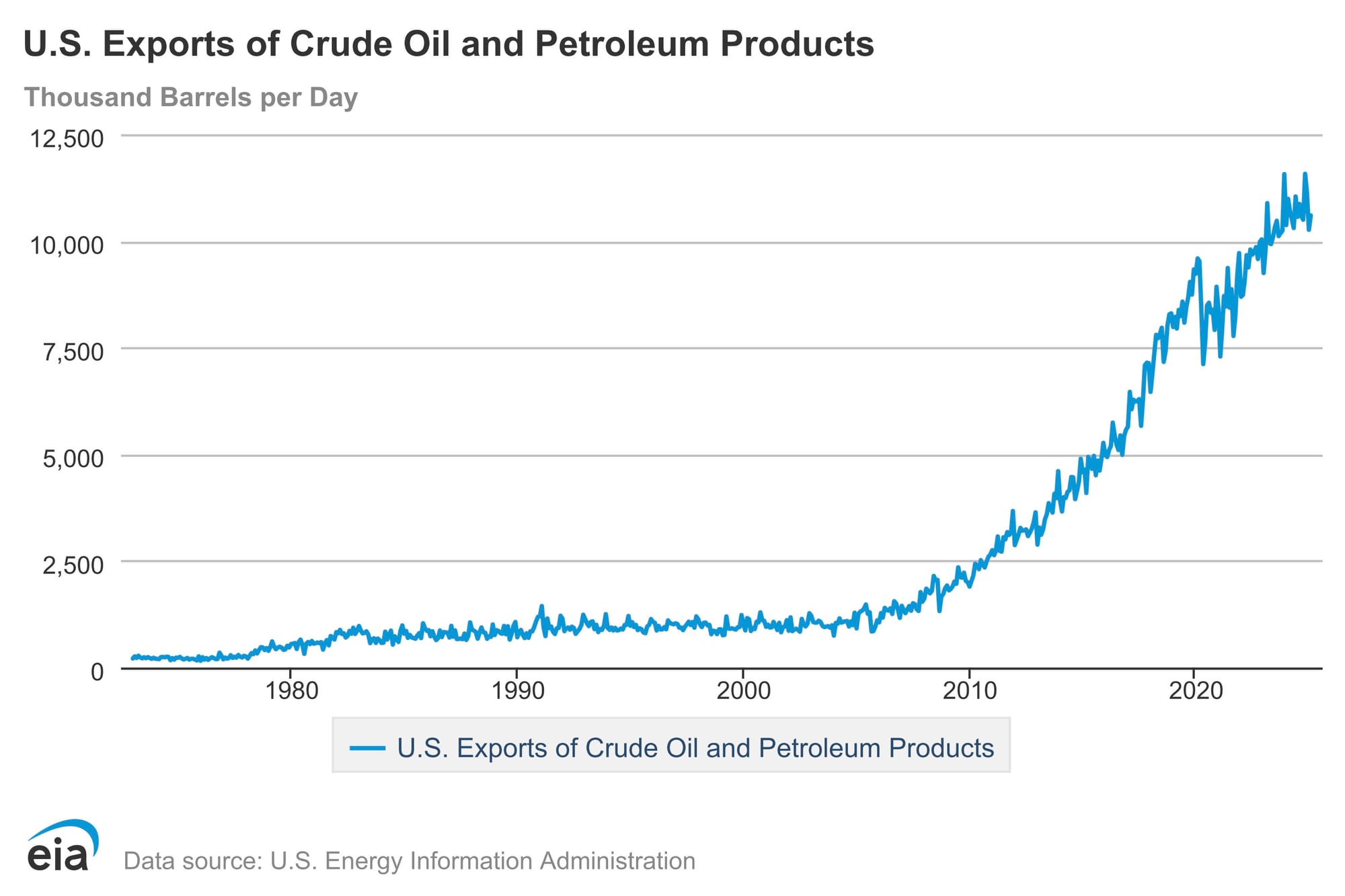

In the mid-aughts, fracking technique refinements enabled the United States to precisely drill for more oil and gas where it would’ve been infeasible earlier.

Two Texas regions benefited from the shale oil boom: The Permian Basin, which spans 75,000 square miles across West Texas and southeastern New Mexico, and the Eagle Ford Formation, a 400-mile-long, 50-mile-wide band beginning in East Texas that snakes between Corpus Christi and San Antonio to the Mexican border.

A decade later, the door to Ingleside on the Bay’s future as an oil export hub opened.

In late 2015, Intent on avoiding a government shutdown, Democratic congressional leaders held secret talks with Republican counterparts and reached a grand bargain. In exchange for an “unprecedented” tax incentive for wind and solar power, President Barack Obama signed a bill that reversed over four decades of energy policy banning oil exports.

The first barrel of exported U.S. crude oil set sail from the Port of Corpus Christi on Dec. 31, 2015.

The change has been rapid, both for the country and for Ingleside on the Bay. For the past six years, the United States has produced more crude oil than any other country at any point in history.

And, “It used to be that we would be out here, and one (oil tanker) would go by every four days. We’re like, ‘Oh, look!’,” said Charlie Boone, the president of the Coastal Watch Association. “It’s 10 a day or more, just back and forth, back and forth.”

Permit renewal sparks protests

Despite being late to the environmental justice movement, Ingleside on the Bay residents are now enmeshed in the fight, along with local Latino and Indigenous allies.

Around 200 residents and advocates trickle into Portland Community Center on the evening of Jan. 11, 2024. They are greeted by Enbridge representatives and staff from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ).

They are gathered to discuss the renewal of Enbridge’s operating permit for the Ingleside site. (Since then, Enbridge has purchased the Flint Hills facility from Koch Industries and now owns two of the three export terminals in Ingleside on the Bay.)

Inside Climate News and The Texas Tribune reported in December 2023 how Enbridge convinced the TCEQ to split the Ingleside Energy Center’s contiguous oil and gas operations into separately permitted sites. The Coastal Watch Association and Environmental Integrity Project charged that the move serves to bypass public participation by exploiting the legal distinction between major and minor pollution sources.

Although Enbridge has received six notices of violation, a then-Corpus Christi City Council member who chairs the local Sierra Club notes that the company maintained a perfect TCEQ compliance record at the time of the hearing.

Tim Doty, retired manager of TCEQ’s mobile air monitoring unit, takes his former colleagues to task, noting the "significant" hydrocarbon emissions from the three facilities.

He questions whether the agency is “rubber-stamping approval,” despite overwhelming opposition from the public. In a written response, TCEQ says the proposed permit has “sufficient” requirements “to demonstrate compliance with the applicable requirements.”

On Feb. 7, 2025, the TCEQ greenlit Enbridge’s permit renewal. This means that Enbridge is on the 1-yard line of a process that would cement five more years of operational risk and greenhouse gas emissions. A final public petition period before the U.S. EPA ended May 27.

Ingleside on the Bay residents and their allies don’t know the ultimate fate of their small town. But if they look across the bay at Corpus Christi’s Black-majority Hillcrest neighborhood, the future may not be bright.

That neighborhood is now a series of abandoned house foundations. Vulnerable residents were cornered, bought out and severed from the rest of the city, first by oil refineries, then by a sewage treatment plant, a towering highway bridge to make way for supertankers and a proposed desalination plant to serve the water needs of the oil and gas industry.

At the hearing, Doty reserves his harshest words for Enbridge.

“You're not doing right by this community,” he says. “You have not been a good neighbor.”

Reporting of this story was supported by the Society of Environmental Journalists, Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources and the Kelly-Douglas Fund at the MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences. The Xylom is the only Asian American-serving science news outlet in the United States.