How the Inflation Reduction Act is playing out in one of the ‘most biased’ states for renewables

Solar developers are going head-to-head with fossil fuel-backed opposition groups and renewable bans in Ohio

Published by the Investigate Midwest, Allegheny Front, The Ohio Capital Journal, Public News Service

This story has been updated to reflect that 24 Ohio counties now have renewable energy restrictions.

Solar farms and wind turbines are popping up across America as a new climate law boosts the economics of renewables through billions of dollars of incentives. But in Ohio, one of the most hostile states for renewables, developers are walking a tightrope.

For the first time, renewable energy in the United States is the same price as energy from burning fossil fuels. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) — the largest investment in combating climate change in U.S. history — has helped developers by boosting tax credits.

But solar advocates and developers in Ohio are pessimistic that the IRA will help them overcome fossil fuel-backed opposition groups spreading misinformation about solar and a harsh regulatory regime in the Republican-run state.

“Ohio is probably one of the most biased states in terms of its treatment of renewables as this catastrophic thing that needs to be limited and banned,” said Dave Anderson, policy and communications manager for the Energy and Policy Institute, a watchdog group that exposes dark money.

The state has set up an uneven playing field that favors fossil fuels. Ohio rebranded gas as “renewable” energy and passed a law, Senate Bill 52, that gives local governments the power to veto solar and wind farms. No such veto power exists for fossil fuel projects.

Developers say SB52 is having a chilling effect on solar projects in a state where only 54% of residents believe climate change is caused by human activities — 4 percentage points less than the national average.

“It’s been pretty nuts to watch how far it’s gone,” Anderson said of SB52.

The law is part of a growing wave of organized opposition to renewables in 41 states, resulting in nearly 400 significant local restrictions against wind, solar and other projects, according to a 2024 report by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School.

How the IRA is playing out in Ohio

At first glance, the Midwestern state might seem like a surprising place for solar. But relatively cheap land, a decent amount of sunshine, plus increasing demand from data centers means solar energy is crucial to meet the state’s future energy needs.

New solar construction in Ohio is set to accelerate to third place among the states by 2027. Ohio recently approved its largest solar installation, the 6,000-acre, 800-megawatt Oak Run project.

Passed in 2022, the IRA is expected to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40% compared to 2005 levels. It would do this mostly by creating $270 billion in tax incentives plus $100 billion in other and other federal subsidies for climate and energy spending.

The biggest boost to solar is the extension of the solar investment tax credit for 10 years, creating long term policy certainty for the industry.

Solar projects that meet certain requirements are eligible for a 30% investment tax credit, and another 10% if the project is in a community that historically relied on fossil fuel production — including shuttered coal facilities — to employ local residents.

The extended tax credit is critical for solar farms: While solar manufacturing plants can start turning out parts within a year or two, it can take up to a decade for solar installation to come online.

In Ohio, solar developers say the IRA is creating momentum for projects that face siting hurdles, interconnection delays, supply chain uncertainty, tariffs, high interest rates and inflation.

The IRA is also contributing to the solar boom in Ohio by driving down costs.

“The costs of panels and mounting equipment, and basically everything tied to a solar farm goes down, because in general, these tax credits and incentives for both small and large products are creating an economy of scale,” explained Nolan Rutschilling, managing director of energy policy for the Ohio Environmental Council. “So we’re seeing the economics price out much better for solar projects and clean energy projects in general because of the IRA.”

Solar factories across the state have benefitted from IRA investment, including manufacturing facilities run by Illuminate USA, First Solar and Toledo Solar.

Illuminate USA has already started firing out solar panels, noted Jack Conness, policy analyst at Energy Innovation: Policy and Technology and creator of a map tracking IRA manufacturing spending.

Illuminate USA also has solar farms in Ohio. “You would hope that creating these (manufacturing) facilities and creating jobs, and hopefully positive conversations around what they’re doing in the community then has some sort of trickle-down impact on solar installations in Ohio,” Conness said.

Lightsource BP, the developer behind three solar farms in Ohio, is seeing benefits from IRA job creation in Ohio, according to Alyssa Edwards, senior vice president of government relations and environmental affairs at Lightsource BP.

“The IRA is bringing benefits to American workers that most definitely is bringing a positive sentiment,” Edwards wrote in an email.

How SB52 blocks solar

While solar development is benefitting from the tailwinds of the IRA, it still faces the headwinds of SB52.

Before SB52 passed in 2021, the Ohio Power Siting Board had exclusive jurisdiction over large energy projects, and counties had no authority to stop them. After SB52 passed, it handed counties new regulatory powers to veto individual projects and establish restricted areas where wind and solar projects are banned.

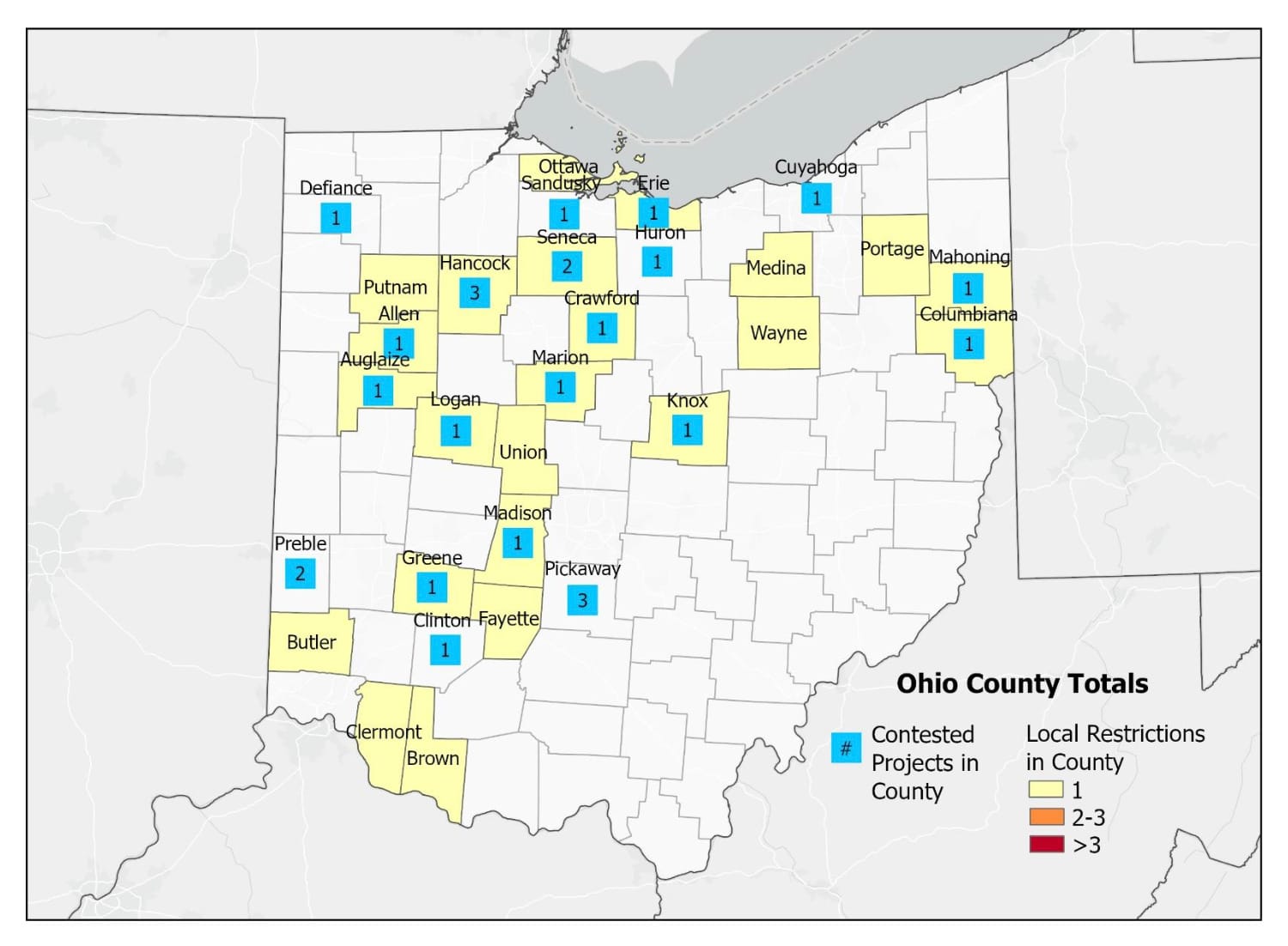

Now, 24 of Ohio’s 88 counties have restricted areas against solar, according to Matthew Eisenson, senior fellow at the Renewable Energy Legal Defense Initiative at the Sabin Center. He said: “This number is going up.”

Added Eisenson: “A really important feature of SB52 is that this is a carve-out just for wind and solar — it doesn’t apply to fossil fuel projects.”

Led by state agency heads with backgrounds in the environment and agriculture, the Ohio Power Siting Board is equipped to make decisions on solar projects, he said, but commissioners at the county level often lack such expertise.

“They’re ordinary citizens, elected by their peers,” Eisenson said. “Some of them run on an anti-solar, anti-wind platform. It’s much more of a political decision at the county level.”

When SB52 was proposed, solar developers struck a compromise with the bill’s sponsors, who were sympathetic to the need for business certainty. They grandfathered in projects that had a significant amount of investment and were deep into the study process, meaning they would move forward under the legacy set of rules.

But new projects that are not grandfathered face the full weight of SB52, meaning they will first be screened by local commissioners before being considered by the Ohio Power Siting Board.

“SB52 adds another hurdle where the county has an opportunity to veto the project or establish a restricted area,” Eisenson explained. “After these grandfathered projects have all been resolved, counties will have the final say on wind and solar projects.”

In short, the state could see a wave of solar construction, followed by relatively little installation.

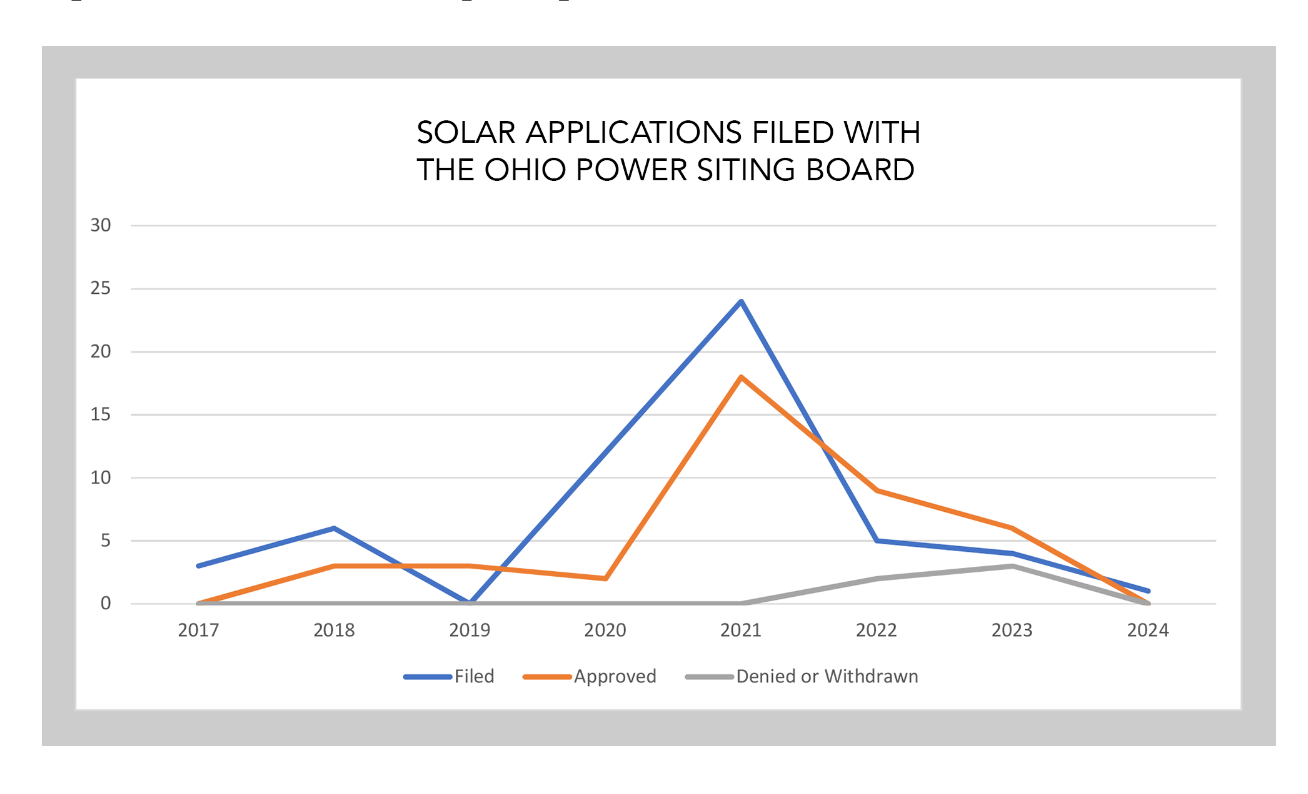

The chilling effect of SB52 is already apparent: solar applications filed with the Ohio Power Siting Board decreased sharply the year it was enacted and have not recovered.

Edwards, of Lightsource BP, didn’t directly comment on SB52, saying only, “As developers of renewable energy, we appreciate a regulatory structure that provides a clear process with certainty and is free from political influence and false narratives.”

Opposition stoked by fossil fuel groups

It was Lightsource BP’s own project, Birch Solar, that became the first large solar project to be rejected by the Ohio Power Siting Board after residents united against it.

In late 2020, opponents began organizing to stop the 300-megawatt, 2,300-acre Birch Solar project near Lima in northern Ohio — starting a Facebook group, establishing Against Birch Solar as an LLC, and launching a GoFundMe to raise $75,000 to fight the project.

The group moved swiftly to engage with policymakers. In December 2020, the group’s leader Jim Thompson met with the Auglaize County Board of Commissioners to ask the board to pass resolutions against the solar farm. In February 2021, the group held a public meeting to stop Birch Solar, attended by the top two legislative leaders: Ohio Senate President Matt Huffman and Ohio House Speaker Bob Cupp.

Weeks later, lawmakers introduced SB52, which was cosponsored by Huffman. Representatives from Against Birch Solar emailed Huffman and scheduled a meeting with him to show support for the law, according to emails obtained through a public records request. Thompson requested amendments and draft language.

The group listed dozens of concerns, outlined in documents sent to Huffman, including visual issues like “glint and glare,” potential harms to wildlife from construction and fencing, stormwater runoff, decreasing property values and a shift away from farming crops.

Thompson received inspiration from a group that has used a hub-and-spoke model to use disinformation about solar to stoke opposition in at least 12 states. Thompson told Floodlight and NPR that Susan Ralston, founder of Citizens for Responsible Solar, gave him advice and connected him with other anti-solar people in Ohio.

It’s unclear who is funding Citizens for Responsible Solar. While Ralston denied that the group received fossil fuel money, Floodlight and NPR reported that her consulting firm received $300,000 from a foundation with ties to coal companies. And while setting up the group, Ralston consulted with John Droz, an anti-wind strategist connected to the fossil fuel industry.

Thompson did not respond to questions, but denied that Against Birch Solar has ties to dark money.

Ohio has a history of fossil fuel groups supporting anti-renewable activists, according to research by the Energy and Policy Institute. The leader of anti-wind group Save Western Ohio was a paid consultant for a fossil fuel-funded think tank. And coal producer Murray Energy secretly paid an attorney to represent locals in their fight against an offshore wind project in Lake Erie.

Another solar project is facing opposition that critics say is linked to fossil fuel interests. Developers are proposing the Frasier Solar project in Knox County, near the headquarters of Ariel Corp., a major manufacturer in the gas industry.

One opposition group, Knox Smart Development, is linked to Ariel Corp. and the Empowerment Alliance, an anti-renewable dark-money group allied with the gas industry. An early version of the Knox Smart Development site had fingerprints of the Empowerment Alliance, including a hyperlink to The Empowerment Alliance with the words “Our Mission: Empowering America.”

Knox Smart Development has hosted town halls and bought advertising targeting locals. According to Energy News Network, speakers at the events include Tom Whatman, chief strategist of Majority Strategies, the highest paid contractor for The Empowerment Alliance. Knox Smart Development, Ariel Corp. and the Empowerment Alliance did not respond to requests for comment.

“They are a dark money organization that definitely is trying to promote fossil fuels and oppose clean energy,” said Rutschilling of the Ohio Environmental Council. “Yes, it’s a problem, but it also shows that the solar industry is growing and gaining and the fossil fuel industry is threatened by that.”

Some solar developers are pessimistic that IRA incentives can overcome SB52. Edwards of Lightsource BP said: “Unfortunately, I don’t believe they (IRA incentives) are enough to overcome such hurdles.”

But Rutschilling thinks the IRA will help swing public opinion.

“We’re seeing a number of programs that were created by the IRA that are going to result in a significant amount of economic development and jobs in the state of Ohio,” he said.

“That will shift the political tide in favor of the clean energy industry.”

This story is part of an occasional series examining the climate impact of the Inflation Reduction Act.