Power for data centers could come at ‘staggering’ cost to consumers

New report highlights how traditional ways of setting rates don’t fit Big Tech’s massive, immediate demand for more electricity

Published by the Arkansas Advocate, Louisiana Illuminator, WWNO, Michigan Advance, Renewable Energy World, Utility Dive

This story was updated to include comment from The Data Center Coalition.

The explosive growth of data centers around the country — driven in large part by the burgeoning use of artificial intelligence — could come at a “staggering” cost for average residents with skyrocketing electricity bills.

A new report from Harvard’s Electricity Law Initiative says unless something changes, all U.S. consumers will pay billions of dollars to build new power plants to serve Big Tech.

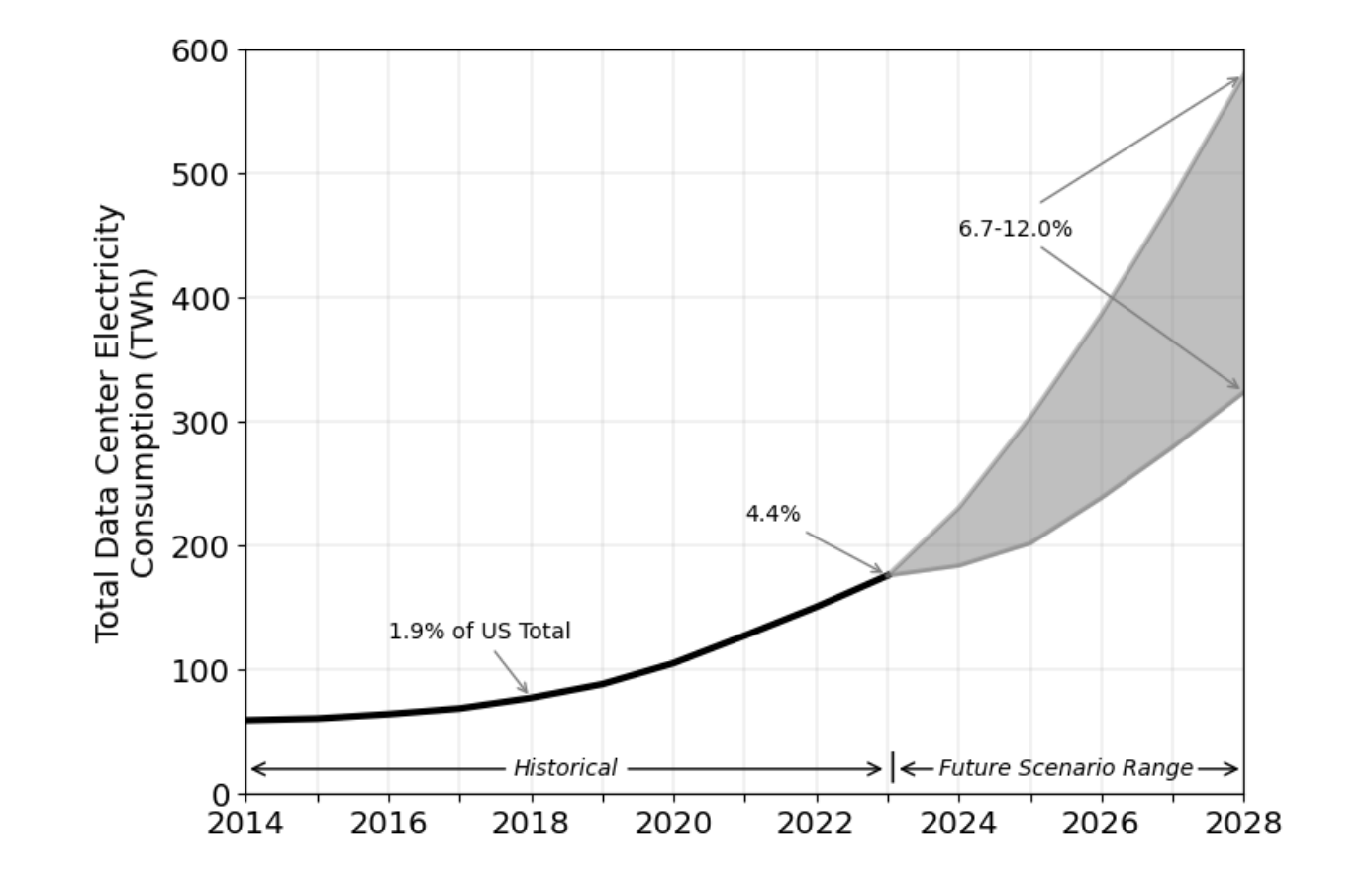

Data centers are forecast to account for up to 12% of all U.S. electricity demand by 2028. They currently use about 4% of all electricity.

Historically, costs for new power plants, powerlines and other infrastructure are paid for by all customers under the belief that everyone benefits from those investments.

“But the staggering power demands of data centers defy this assumption,” the report argues.

“We’re all paying for the energy costs of the world’s wealthiest corporations,” said report author Ari Peskoe, director of the initiative at the Harvard Law School Environmental and Energy Law Program. He worked with co-author Eliza Martin to produce the report, “Extracting Profits from the Public: How Utility Ratepayers are Paying for Big Tech’s Power.”

Lucas Fykes, director of energy policy for The Data Center Coalition, which advocates for the industry, responded to Floodlight by email, saying, “State utility commissions have the regulatory responsibility and authority, expertise, experience and processes in place to ensure that cost allocation and rate design are fair and reasonable for all customers.”

A spokesperson for Dominion, which serves one of the nation’s largest data center loads in Virginia, said establishing rates in the state is an “open and transparent” process.

Aaron Mitchell, vice president of pricing and planning at Georgia Power, testified to a Georgia legislative committee that adding 3,300 megawatts (MW) of new generation for data centers —or enough to power roughly three million homes — will actually reduce customers’ bills.

“The more that we are able to serve, the more that we can provide benefits to existing customers, by virtue of those new customers coming online and paying their fair share of the costs that we incur to serve those customers,” Mitchell said.

Secrecy hides full picture of utility costs

But Martin and Peskoe examined nearly 50 regulatory proceedings around the country between utilities and data centers to determine who pays the costs for electricity for data centers.

In many cases, agreements between tech companies and utilities are confidential, limiting the information that’s available including how much electricity a data center will use and how much it will pay for the power, according to the report.

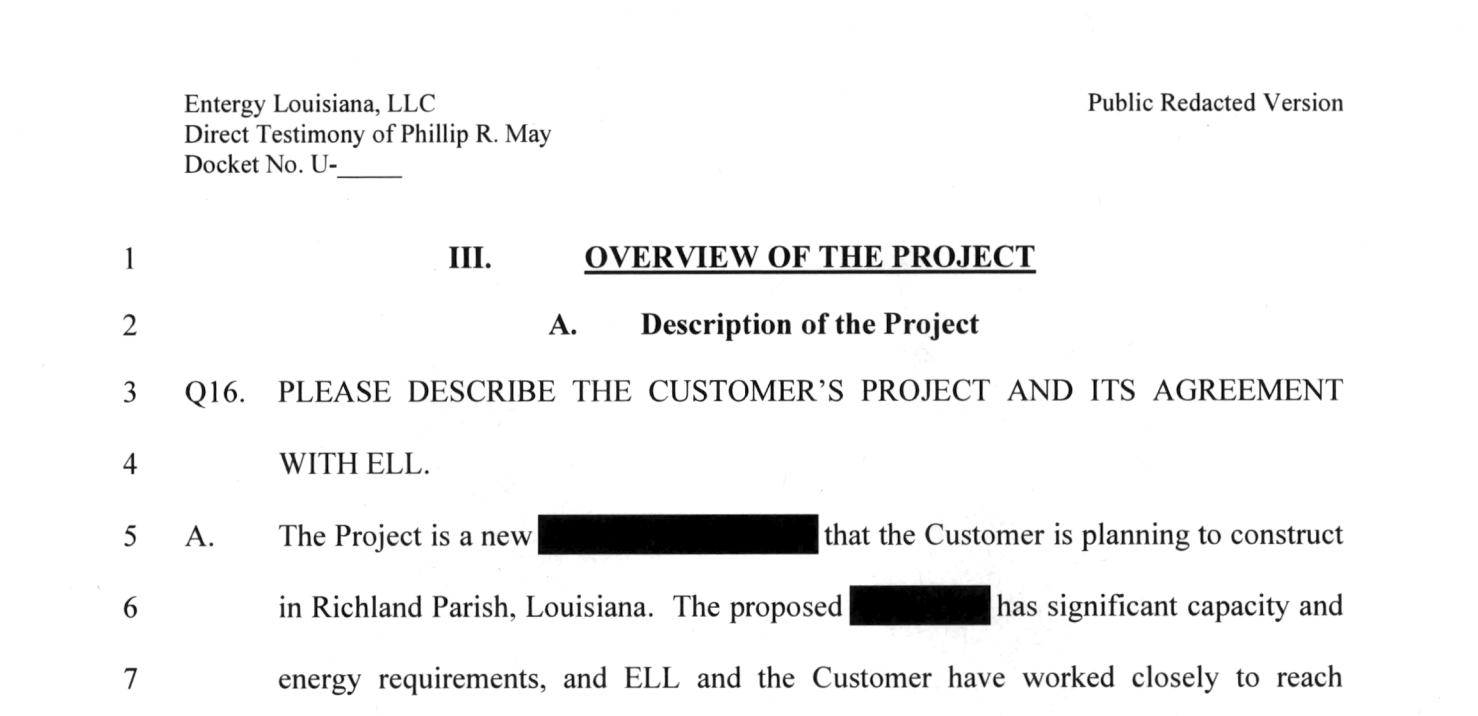

In Louisiana, Entergy Louisiana is proposing to build 2,250 MW of new natural gas generation for Meta, the tech company. But neither Meta nor its data center affiliate Laidley, is involved in the proposal before the state’s Public Service Commission.

Earthjustice, a nonprofit environmental law organization, is an intervenor in Entergy Louisiana’s request to build new gas plants to fuel the Meta data center. The group filed a motion with the PSC seeking to force Meta, the parent company of Facebook, and Laidley to disclose information including anticipated energy demand, justification for its request for an expedited approval and verification of how many local jobs it will create.

Peskoe and Martin found that in some cases, utilities appear to have hidden how much average residents pay to offset special rates or incentives given to other customers, including data centers. The report cites a lawsuit against Duke Energy that alleges Duke intentionally hid a $325 million discount provided to a large customer and, according to internal documents, that Duke planned to “shift the cost” to other ratepayers.

“We should be skeptical of utility claims that data center energy costs are isolated from other consumers’ bills,” the report says.

The potential costs aren’t just in bill increases, the paper points out. If utilities can profit from building new generation for data centers, they have no incentive to modernize their systems by switching to renewable or more efficient power, which would provide longer term benefits to customers and the climate.

Rather than adding cleaner, renewable sources, “utilities … are instead offering to meet data center demand with transmission (upgrades) and gas-fired power plants, which have been the industry’s bread-and-butter for decades,” according to the report. “Some utilities are even propping up their oldest and dirtiest power plants to meet data center demand.”

Daniel Tait is a research and communication director for the utility watchdog Energy and Policy Institute. In February, Tait released an analysis about how the demand for data center power has caused utilities, mostly in the South, to continue operating coal-fired power plants — some of them on the verge of closure. Such a move would stall or reverse efforts to decarbonize the electric sector, he wrote.

Size of energy demand, benefits, hard to find

State utility regulators are often under pressure to approve data centers because of their perceived benefits, the report says.

That dynamic is playing out in Louisiana, where the Public Service Commission agreed to fast-track approval of $3.2 billion in new natural gas-fired generation to serve a $10 billion Meta data center. The announcement had one normally skeptical commissioner labeling the proposed development in economically impoverished North Louisiana a “godsend.”

In its initial filing — in which key information was redacted — Entergy told the PSC the data center would provide 300 to 500 jobs. But Entergy later said it couldn’t provide evidence of those jobs. Meta did not respond to a question about the number of jobs and whether they would be located in Louisiana.

Entergy spokesman Brandon Scardigli confirmed that Meta has guaranteed it will pay the costs for the new generation for 15 years. But, he said he couldn’t comment on the specific economic impacts of the data center, including the number of jobs it would create. The data center, he said, “represents a major investment in the state.”

Tait questioned whether the promised jobs would ever come.

“Here's what's so sick about this, is that they are doing this in a deeply impoverished area of Louisiana, with the presupposition that they're doing it to bring wealth and jobs to that area of the state, right?” he said.

Using its access to the confidential agreements made with Entergy Louisiana, Earthjustice is examining how costs may be spread to other customers in the state — and what happens after the 15-year contract ends.

“Our argument is that the ratepayers don't actually benefit from the existence of this data center in this spot,” said Susan Miller, the lead Earthjustice attorney in the case. “They should not be paying greatly increased utility rates just so that the data center can have a business.”

The Harvard report makes the same point, arguing that data centers don’t need subsidized rates if they are already receiving other incentives from a state to locate there. In 2023, for instance, Virginia data centers were exempted from paying $1 billion in sales tax, the report says.

In Louisiana, Meta will receive, among other things, a use and sales tax exemption on data center equipment and software. The amount, which isn’t specified, is contingent on the data center creating 50 direct, permanent new in-state jobs and spending at least $200 million in new capital.

Can ratepayers, taxpayers be protected?

To prevent a “race to the bottom,” the report recommends that U.S. public utility commissions require the same terms and rates for all data centers.

The report said utility commissions also could establish “robust” guidelines, like those in Kentucky. There, a utility can only provide a discounted rate for service when it already has excess generation. It also requires that any special contract rate exceed the cost of providing the power and that the discount extend for no more than five years.

Kent Chandler, former chairman of the Kentucky Public Service Commission, said the state has handled special contracts that way for 35 years.

“We’ve laid out rules for the utilities, saying you should only offer these when these circumstances exist and in this way,” Chandler said. “And I think that that served the state particularly well. Kentucky still has a robust manufacturing base.”

Chandler argues that a new regulatory regime isn’t necessary to handle data center demand, but “quality implementation” would go “a long way in alleviating a lot of the concerns” raised in the Harvard paper.

He says one way to protect ratepayers is to allow data centers to contract directly with independent electricity providers. The paper also envisions the creation of “energy parks” where power is provided to a cluster of data centers. That park might not even be connected to the grid, to “completely insulate ratepayers from data centers’ energy costs.”

The growth is occurring so quickly that regulators are grappling with the issue on the fly. Louisiana Commissioner Davante Lewis said he welcomes the economic development Meta could bring but still lacks a full understanding of the long-term repercussions of any deal.

Said Lewis: “I have to do extra due diligence to ensure the people of Louisiana don't get stuck with a ginormous bill because we were promised a bunch of economic development that happened in a very secret way that I don't think was good for the public.”

Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.