Public utility commissions are exceptionally white. It’s hurting black residents.

As the new head of a group of conservation voters in Georgia, Brionté McCorkle wanted to sit down with regulators who oversee the state’s utilities to talk about carbon emissions.

Published in Capital B

As the new head of a group of conservation voters in Georgia, Brionté McCorkle wanted to sit down with regulators who oversee the state’s utilities to talk about carbon emissions. But when she got a meeting with one of those regulators, she realized there were deeper problems. The regulator she spoke with didn’t understand the people he served.

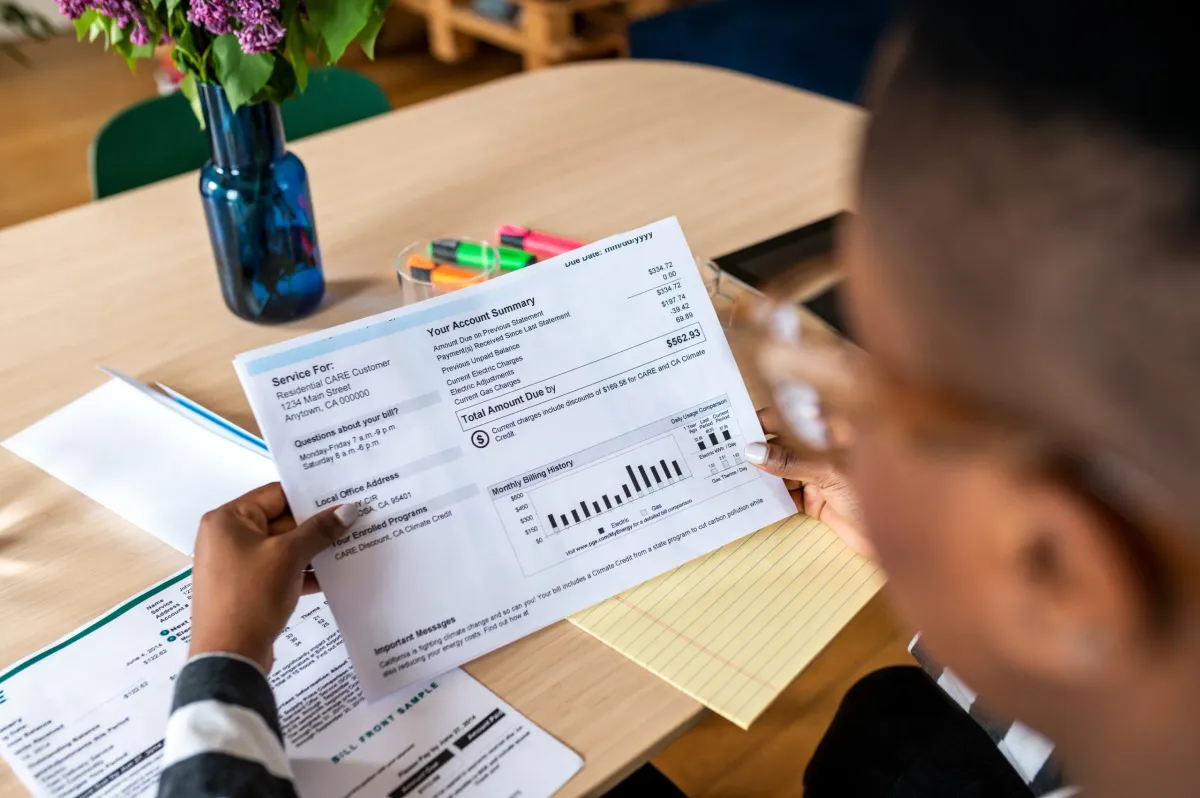

While 40% of the state’s households earn less than $40,000 a year, the regulator couldn’t understand why some of his constituents don’t have enough money to pay their power bills. McCorkle understood all too well. Growing up, her grandmother would turn off the lights at night to save money. She remembers her grandmother saying, “We’re going to sit in the dark tonight.”

McCorkle said the public service commissioner she met with “was wildly out of touch” with 40% of the state’s population.

The demographics of utility regulators and how they are elected matters, say McCorkle and others, because majority-white utility commissions have historically resulted in inequitable outcomes for Black and other minority communities.

With the increasing dangers of climate change, and billions of dollars from last year’s Inflation Reduction Act targeted to address those dangers, it could be a matter of life and death where those funds — many of which will be directed by utility commissions — go. The existing disparities could worsen if the system isn’t fixed, says McCorkle, who sued Georgia to change the way utility regulators are elected.

“State regulators are the most critical pieces on how the energy transition is going,” said Chris Villarreal, an associate with the R Street Institute, a center-right think tank that supports a more competitive electricity market.

Over the last 100 years, Georgia, which has the second-highest population of Black people in the nation, has had just two Black members on its public service commission. And all commissioners are elected, not by districts, but by the entire state, which is predominantly white.

Broadly speaking, utility regulators are appointed in 40 states and elected in 10 others. Georgia is one of six states where commissioners are elected at large. Regardless of how regulators are chosen, politics always finds its way into the decision-making process, one Wall Street analyst said.

“There’s no way to eliminate the political influence,” because it’s embedded in the process, said Travis Miller, an energy and utilities strategist at Morningstar Research Services LLC.

Recent commission decisions in Georgia that have hit low-income residents hard include votes to raise basic electricity rates, push soaring costs of two nuclear reactors onto customer bills, and allow Georgia Power to start disconnecting customers who weren’t paying their bills just months into the COVID-19 pandemic.

Georgia isn’t alone. A Brown University Climate and Development Lab report showed the historically all-white Alabama Public Service Commission has resulted in “particularly egregious energy equity outcomes for the state,” by allowing rate increases without a formal vetting process to gain input from consumer and environmental advocates and by approving utility-proposed economic roadblocks to rooftop solar, among other things.

Alabama suffers some of the nation’s worst low-income energy burdens — with electricity bills consuming more than 10% of low-income ratepayers’ income. Households with higher income pay less than 3% of their income on power bills in the state, according to figures from the U.S. Department of Energy.

The lawsuit brought by McCorkle and two other Black voters in 2020 argued the at-large voting system illegally dilutes the voting power of Black residents, violating the federal Voting Rights Act and disproportionately affecting Black voters, who spend a higher percentage of their household income on utility bills.

That the five members are elected to serve six-year staggered terms; require a majority vote; and are in unusually large voting districts all “enhance the opportunity for discrimination against African Americans,” the suit said.

What’s more, Stephen Popick, an expert witness who previously worked in the U.S. Justice Department’s civil rights division, testified that his analysis of the PSC’s general elections since 2012 “is one of the clearest examples of racially polarized voting” he has ever seen.

The disparity between the racial makeup of a utility commission and those they serve is most apparent in four Southeastern states where the number of Black commissioners can be counted on one hand. Alabama and Mississippi have had no Black commissioners.

Georgia has had just two Black commissioners in its 100-year history, both appointed by governors to fill a vacancy, including one appointed in 2021. Louisiana just elected its second Black utility regulator last year, Davante Lewis, who wants more renewable energy and reduced late fees for customers who can’t pay their utility bills on time in a state where energy bills are disproportionately high for lower income residents.

A study from the Chisholm Legacy Project, a nonprofit focused on environmental justice and helping communities that are near now-shuttered fossil fuel plants, showed even just one Black regulator on a commission can help residents in marginalized communities.

In Arizona, Sandra Kennedy, a commissioner of color, successfully lowered the threshold on utility shutoffs for nonpayment to 90 degrees from 95, arguing that this would help prevent heat-related deaths.

In Michigan, Tremaine Phillips, with the help of grassroots organizations, sought input on how to include environmental justice and public health into long-term energy planning in efforts to reduce adverse climate and health outcomes for the state’s most vulnerable communities.

McCorkle said real representation is needed, and the best way to do that is to be able to hold elected officials accountable through fair elections.

“I feel like I’ve done something meaningful to get better representation,” she said.

Floodlight depends on a community of readers like you who are committed to supporting nonprofit investigative journalism. Donate to see more stories like this one.