Removing carbon from the air — a climate cure or waste of money?

The incoming Trump administration will have a say in whether federally backed direct air capture projects in Louisiana move forward

Published by WWNO, Louisiana Illuminator

After fighting oil, gas and petrochemical expansion in southwest Louisiana for more than 50 years, retired biologist Michael Tritico might be expected to applaud a new facility that promises to suck carbon dioxide out of the air to reduce global warming.

But that's not how Tritico sees the U.S. Department of Energy-backed direct air capture facilities proposed for Calcasieu and Caddo parishes.

“The political locking-in of Southwest Louisiana as a fossil fuel centerpiece has taken on a new facet — carbon capture and sequestration,” Tritico said of the facilities, collectively called Project Cypress, announced last year.

His concerns haven’t diminished since that announcement. Tritico was one of the few residents who attended a DOE environmental scoping meeting for the project Nov. 21 in Vinton, where one of the two parts of the project would be sited. Another meeting was held a day earlier in Shreveport, close to the other location for the sprawling $1 billion project.

Unlike technology on industrial facilities that captures carbon from a plant’s emissions, direct air capture (DAC) sucks in ambient air and uses chemicals and heat, among other means, to extract carbon dioxide from it.

Critics say the technology is too expensive and energy-intensive to make a sizable dent in carbon concentrations. While carbon emissions from a coal-fired power plant can contain up to 15% carbon dioxide, the atmosphere contains just .04% carbon.

Tritico's greatest worry is that the pipeline carrying carbon dioxide captured from the air in Calcasieu Parish and Shreveport to central Louisiana — where it would be injected underground — could leak or rupture. That would displace the oxygen in the air, threatening the lives of people who live along the pipelines. He thinks, though, another argument might have more weight with the incoming Trump administration — that Project Cypress is a waste of money.

“Millions of dollars in taxpayer money for what amounts to an experiment,” he said after giving his comments to the DOE meeting. “That's going to be interesting to see under this new administration, if they're really serious about saving taxpayer money — because this is a good example. Hundreds of millions of dollars of taxpayer money for something that's quite likely inefficient.”

A new paper from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Energy Initiative echoes that conclusion. It warns that it would take 40% of the world’s electricity to remove one-fourth of the carbon emitted each year — and that the technology is unlikely to be a major solution to climate change.

The research team recommended, however, that “work to develop the DAC technology continue so that it’s ready to help with the energy transition — even if it’s not the silver bullet that solves the world’s decarbonization challenge.”

Trump has repeatedly vowed to slash climate spending under the Inflation Reduction Act, but the direct air capture hubs are part of the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Act. The IRA, however, does provide a $180 per ton of carbon subsidy for direct air capture that Project Cypress would apply for once operational.

DAC considered key technology

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the Biden administration, among others, say direct air capture will be necessary under most scenarios to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

To reduce the technology's costs and improve its efficiency, Congress gave DOE $3.5 billion to fund so-called DAC hubs. The energy agency has awarded a portion of the funds — $50 million each to Project Cypress and a hub in south Texas. Depending on how the projects progress, each could qualify for half a billion dollars in additional federal funding, the DOE said.

The south Texas project is owned by a subsidiary of Occidental Petroleum, whose CEO has said carbon capture is a way to “preserve our industry over time” — feeding concerns that DAC will let oil and gas to keep emitting greenhouse gasses at their current rate.

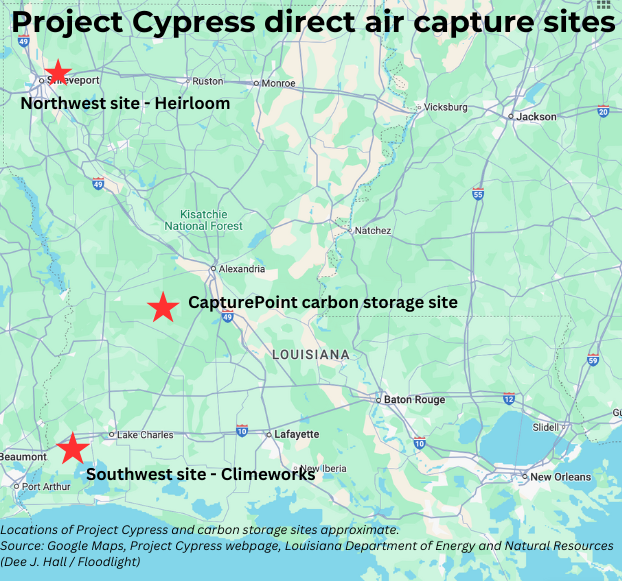

The Louisiana project, which would be managed by nonprofit scientific and research giant, Batelle, will consist of two separate DAC facilities using different capture technologies.

Even though the Project Cypress site in Calcasieu Parish is near carbon-intensive industries, CO2 disperses so quickly that the amount of carbon captured at the sites won’t be greater than anywhere else. Louisiana was selected because its geology is suited to sequestering carbon deep underground, according to DOE.

Both facilities have contracted with CapturePoint Solutions to transport the captured carbon to its storage site in central Louisiana — the pipeline that worries Tritico. CapturePoint also has proposed using land underneath U.S. forests to store captured carbon.

Climeworks plans to build its portion of Project Cypress near the Port of Vinton, just south of Sulphur, in Calcasieu Parish. Cllimeworks has demonstrated its technology at facilities in Iceland. It would use huge fans to move air through filters with chemicals to capture the carbon. Scheduled to come online in 2029, the facility would capture up to 300,000 tons of CO2 a year and ramp up to one million tons a year, according to Climeworks.

A second Project Cypress facility is planned for a site about 200 miles north by the company Heirloom at the Port of Caddo-Bossier in Shreveport. Modified limestone would be used to capture carbon at that facility, a technology that has been tested at Heirloom’s California plant. In its initial phase, starting in 2027, Heirloom estimates it would capture up to 100,000 tons of CO2 a year, ramping up to 300,000 tons annually.

Can direct air capture scale up enough to help?

Considering humans produce about 40 billion tons of carbon dioxide a year, however, scientists and others question the viability of scaling up direct air capture facilities to a significant level.

The paper from MIT’s Energy Initiative notes that the sheer number of pipelines, storage sites and locations necessary for wide scale direct air capture are also obstacles.

Direct air capture is a “very seductive concept,” because it could reduce carbon in the atmosphere without disrupting key portions of the world’s economy, especially carbon-intensive industries, the researchers said. But, “Given the high stakes of climate change, it is foolhardy to rely on DAC to be the hero that comes to our rescue,” the paper concludes.

The MIT researchers also warn that if the electricity used to power the DAC hubs is generated by fossil fuels, it could produce more carbon than the facility captures. In one example, the paper says if a DAC facility uses coal-powered electricity, it would actually produce more carbon than it captures.

Climeworks is working with Entergy, the Louisiana utility that would provide electricity to both Project Cypress locations. Entergy gets about half of its electricity from natural gas, a quarter from nuclear, 2% from coal and 3% from renewable energy.

Climeworks will “be working to support new, clean energy generation coming onto the grid to help address our project needs,” company spokesperson Kate Dmytrenko said. “This will either happen through our partnership with Entergy or directly engaging with renewable energy projects or potentially some combination of both to address the needs of the project in a clean and reliable manner.”

But even if renewable energy is used to power the facilities, DAC remains an inefficient technology — one that would worsen, not alleviate, carbon pollution, says Mark Z. Jacobson, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford University. Jacobson says it would be better to shut down existing fossil fuel operations and replace them with renewable energy than send that energy to direct air capture facilities.

“DAC is an opportunity cost,” Jacobson said in an email, “that increases CO2, air pollution, fossil mining, fossil infrastructure and overall social costs (energy costs + health costs + climate costs) by a factor of 10 compared with using the same money to replace fossil sources with clean, renewable energy.”

Louisiana officials bullish on DAC

Despite the concerns, state and local governments are welcoming the DAC project.

“The expansion of Project Cypress Direct Air Capture Hub across the state represents the best of Louisiana — cutting-edge technology at the forefront of the energy economy, powered by innovation and a broad base of highly skilled workers,” Republican Gov. Jeff Landry said in a June news release.

In an interview at the Nov. 21 DOE meeting, Haley Bellard, a lifelong resident of Vinton who sits on the Port of Vinton’s board, said he thinks the project is a good compromise for green energy.

“Obviously, any plant is going to be looked at negatively in some way, but there are a lot of positives. Let’s look at the positives,” he said.

MIT, despite its criticisms, says research to refine DAC should continue, “because it may be needed for meeting net-zero emissions goals, especially given the current pace of emissions.”

DOE is seeking public comment on the scope of its environmental review until Dec. 16. The draft environmental review is expected by June of next year.

Eva Tesfaye of WWNO/WRKF contributed to this report. Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.