Small farmers cry for help as climate change keeps killing crops

Some are asking Congress to add more crop insurance and disaster assistance for smaller producers in the upcoming US Farm Bill.

Published in WWNO, Verite, and Louisiana Illuminator

Iriel Edwards is a first-generation farmer from Louisiana. In her short tenure as a farmer, Edwards, 25, has already seen extreme drought, freezes, flooding and excessive heat.

Edwards, along with thousands of other growers across the country, faces a conundrum nearly every growing season: how to stay afloat when shifting weather patterns caused by climate change keep wrecking their crops?

“It’s something we’re all kind of dealing with,” said Edwards, who is certification coordinator for the Real Organic Project and grows vegetables and seed crops on nine acres of land.

“Last year was difficult, especially with the drought,” she recalled while attending a January summit for small farmers struggling with climate change in southern Louisiana’s Cajun Country. “This year we’ve had large downpours. We're still in a drought, but the rain is coming all at once. (The crops) will flood really easily. Or they don’t grow because they’re waterlogged.”

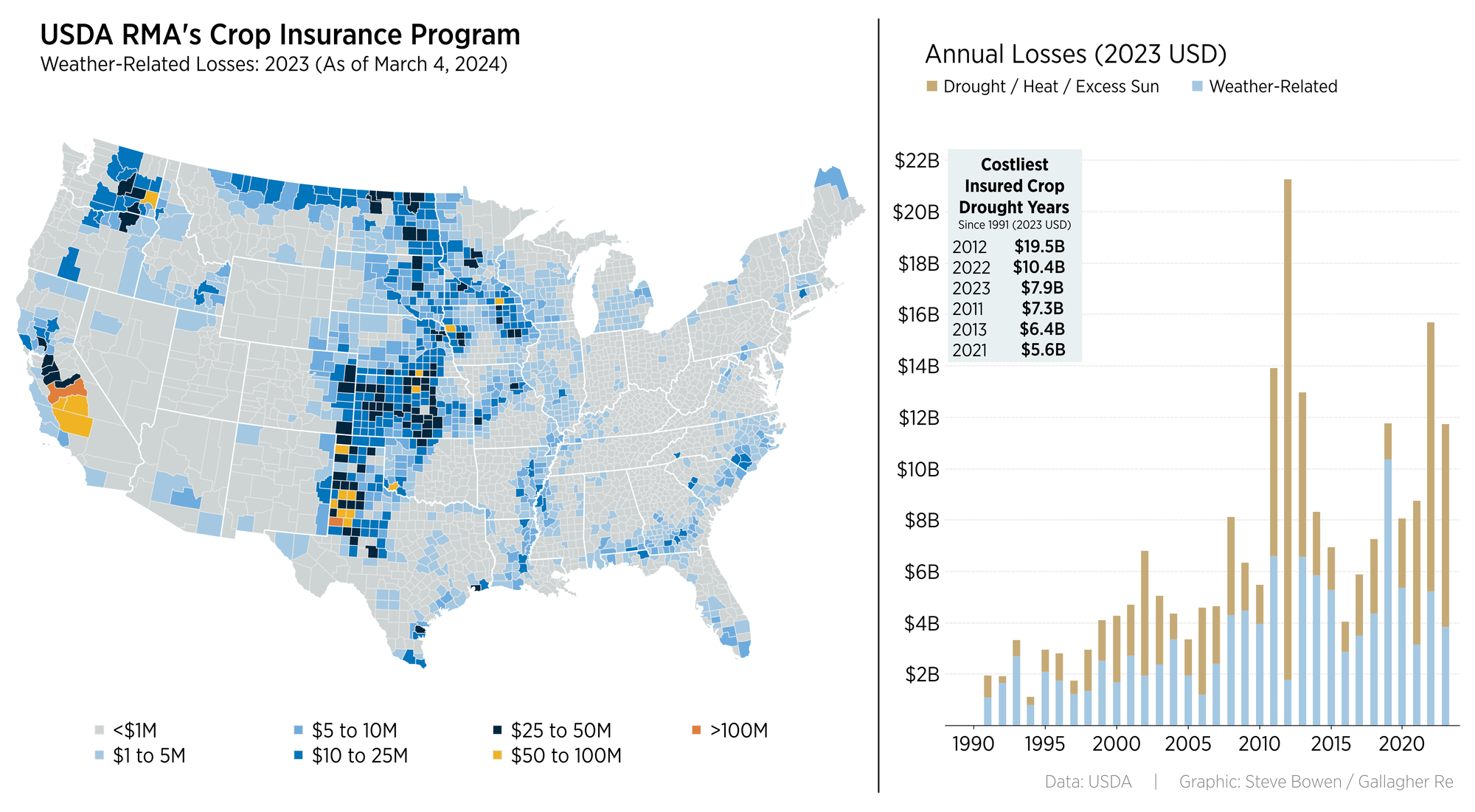

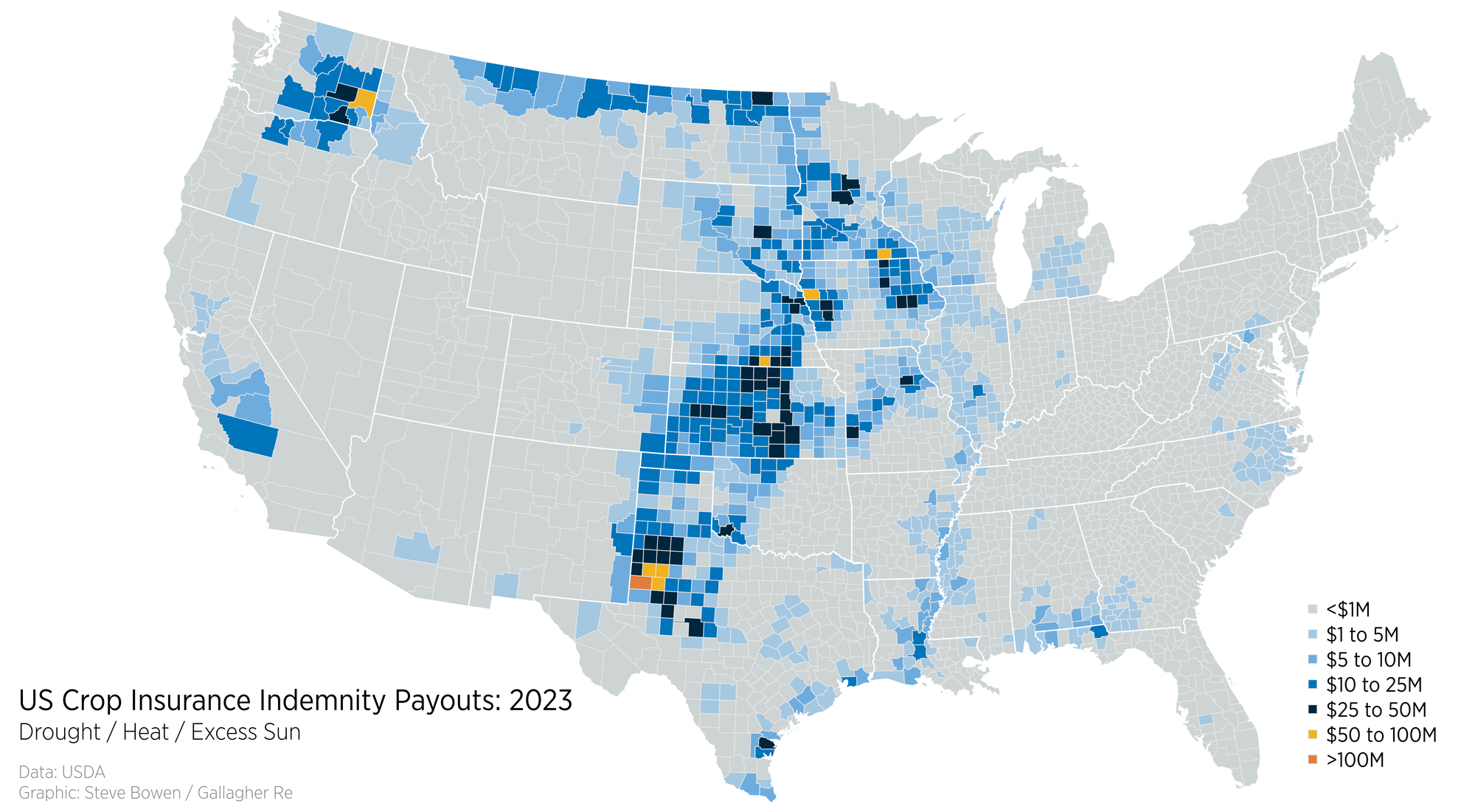

The last two years have been some of the most costly for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which paid more than $16 billion to farmers who lost crops due to drought, excessive heat and other extreme weather.

The reported crop insurance payouts in 2022 and 2023 ranked the second and third highest, respectively, in the past 30 years. The increases are partially attributed to climate change, which is having a growing impact on U.S. farming.

But farmers with smaller acreage say they don’t have the same opportunities to recoup their losses, even though they face the same weather-related challenges as larger farms that disproportionately benefit from federally-subsidized crop insurance programs.

The USDA has made efforts to correct that through programs including the Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program, Micro Farm Program and the Whole Farm Revenue Protection Program. But advocates criticize the noninsured program because it is tailored more toward single-crop farms while many small-scale farmers grow a diverse array of crops. The paperwork required to apply for insurance for such diversified farms is so burdensome that many cannot justify the investment of time for such small returns, advocates say.

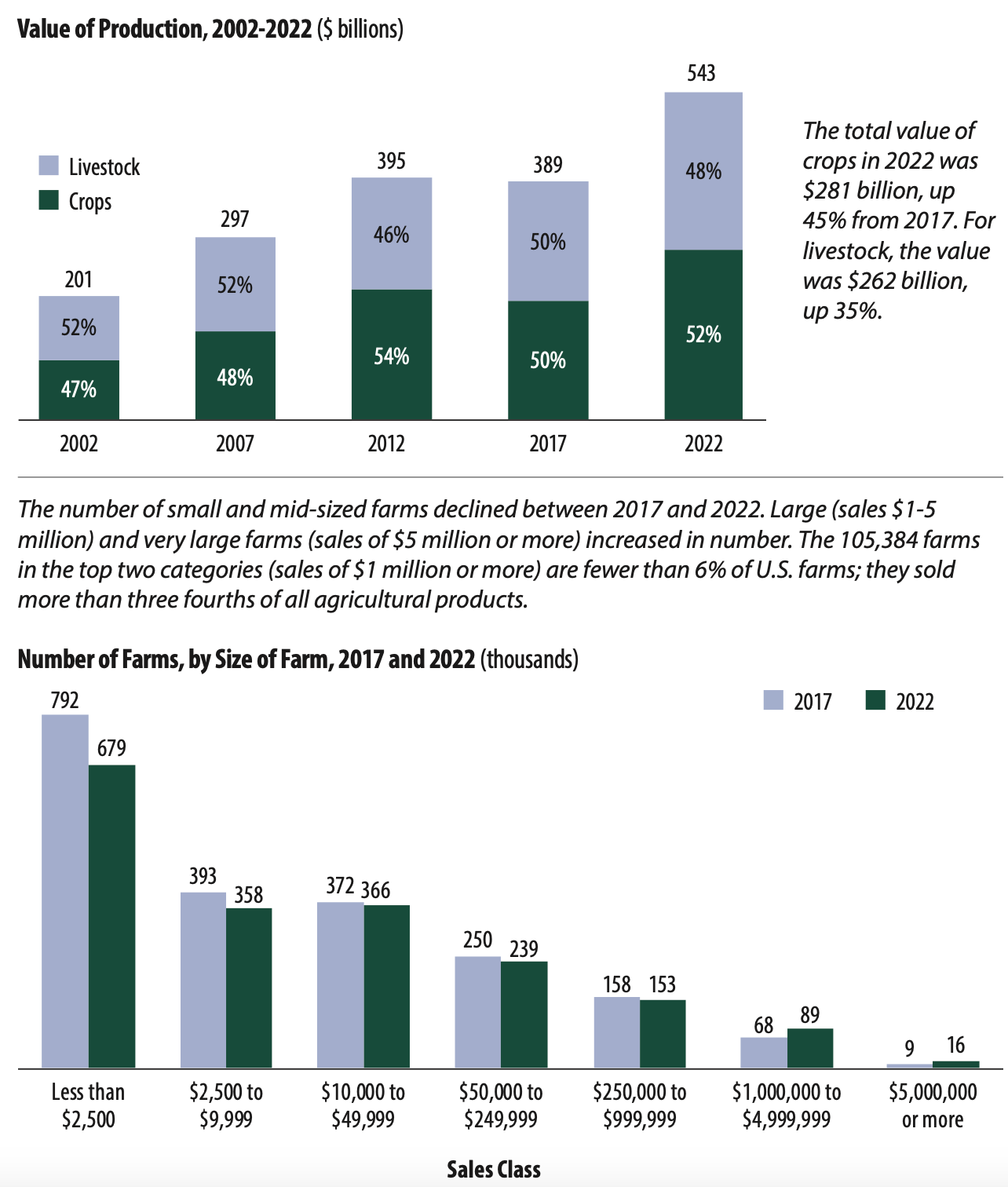

While the overall agricultural sector continues to grow rapidly in the United States, the number of small farms has steadily dwindled. Those small producers who do remain say the feds aren’t doing enough to help them stay in business.

“If the USDA could adapt their programs and policies to meet the changing needs of farmers today — like providing things like crop insurance to small-scale farmers which they currently do not do — that would be a big deal,” said Chris Gang, another young farmer who grows flowers for the commercial market in New Orleans. “We need to rebuild our food system from the ground up. And that means rebuilding USDA, and its policies, from the ground up.”

Congress eyes massive Farm Bill

Gang and other small-scale farmers hope Congress will include more help in the impending U.S. Farm Bill, which is up for approval this fall.

The huge bill comes every five years and covers numerous programs, including food assistance — which makes up the lion’s share of the cost. It is projected to cost $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years. The bill provides support for farmers, ranchers and forest stewards through various means including loans, assistance to support conservation and subsidized insurance to compensate for crop and livestock losses.

A Democratic-sponsored bill seeks a series of changes in the Whole Farm Revenue Protection Program to make it more accessible to small and early-career farmers, according to co-sponsor Sen. John Fetterman of Pennsylvania. So far, the bill, introduced in July, has not made it out of committee.

“The Farm Bill works great for some farmers, but we need a crop insurance program that covers more than just large, corporate commodity farmers,” Fetterman said in a statement. “Small, new, and specialty crop producers that feed their communities deserve a safety net.”

USDA officials say they understand the plight of smaller farmers. They are working on expansions to crop insurance programs, says Marcia Bunger, head administrator of the USDA’s Risk Management Agency, which subsidizes crop and commodity insurance for qualifying farmers.

Bunger says the agency recently implemented a pilot program aimed at training, recruiting and licensing more crop insurance agents and loss adjusters from underserved communities, in addition to offering insurance programs aimed at smaller producers.

“I think we really need to keep our eye on the ball, you know, to maintain national food security, so that we keep as many farmers as possible” and to “allow entry of those that want to enter into agriculture regardless of what they want to grow and their size.” Bunger said.

Giant losses expected to continue

Steve Bowen, chief science officer for global reinsurance broker Gallagher Re, attributes the spikes in annual payouts from the USDA over the last 30 years primarily to droughts and excessive heat waves. In 2023, some counties in California, Texas and the Midwest saw crop losses covered by federally subsidized insurance in the tens of millions of dollars, according to the USDA data.

Bowen, a former meteorologist, expects the trend to continue as extreme weather patterns escalate and more farmers turn to crop insurance. He questions whether the federal government will have enough money to cover future losses.

“The National Flood Insurance Program, we're all very aware of it being $20-plus billion dollars in debt continually because it's just not taking in nearly enough premiums to offset the claims that are being paid out,” Bowen said.

“There aren’t any concerns — yet — that the USDA program is going to be facing the struggles that NFIP is. But again, you have to be mindful of the fact that there just is more stress going on farmers right now, with more of these weather-related claims becoming more and more frequent.”

The American Farm Bureau supports expansions within federally-subsidized crop insurance programs but stops short of attributing increases in loss payouts to climate change.

Sam Kieffer, vice president of public policy for the AFB, said the weather has always been an unpredictable partner for farmers.

“Most of the increases in the cost of crop insurance are linked to an increase in participation and the value of crops that are insured,” Kieffer said. USDA figures show the value of crops produced in the United States has shot up 45% just since 2017.

Kieffer says the USDA has increased the number of insurance plan types from 18 in 2020 to 31 in 2023 using a public-private partnership model.

“More coverage options and the addition of new crop types being covered attract more interest and enrollment from farmers,” he said. “Today, farmers can insure more crops in more places and for more perils than before, all of which results in higher program costs.”

‘It’s quite hard to be a farmer’

The recently released Census of Agriculture tracked a 6.9% decrease in the number of farms between 2017 and 2022 but found at the same time the number of young producers increased slightly — by nearly 4% — over the past five years.

Bruno Sagrera, a sixth generation farmer, is one of them. He recalls that his family discouraged him from continuing the family’s legacy producing crawfish, rice and cattle in southwest Louisiana. Sagrera was instead encouraged to travel the world, pursue higher education and get a job with better pay and less manual labor.

The 25-year-old went to college and he did see the world. But now he is back, helping to raise his son and working his own small-scale farm. Sagrera says it felt important to work with other farmers to build a stronger localized food system.

The medicinal herbs farmer quickly learned that farming today has drastically changed from what it was in the heydays of his father and grandfather, largely because of the intensified drought and flooding.

“I've been doing landscaping for the last two years to pay the bills, because you know, it's quite hard to be a farmer, especially a small farmer,” Sagrera said.

‘We’re all trying to catch up’

Small-scale farmers in Louisiana and elsewhere want more acknowledgement, through the Farm Bill, of the challenges and impacts they face because of climate change.

Provisions in the 2018 bill were extended by President Joe Biden until Sept. 30, at which time a new five-year plan has to be adopted.

The fact that the climate is changing farming so quickly makes it hard to adapt, says Marguerite Green, director of the New Orleans-based farming advocacy group Sprout.

“We don't have institutions we can look to that are on the cutting edge of this yet, because it's happening to all of us at the same time,” Green said. “It's no slight to our research institutions or the USDA. It's just that we're all trying to catch up. Because the climate crisis is emergent. We cannot know what is happening next.”

Sprout was the sponsor of the January conference focused on the growing impacts that climate change is having on small-scale farming. Green says her group was driven to host the event after outreach within their network revealed the mental anguish and financial stresses farmers felt due to the extreme freezes, heat, droughts and wildfires they faced last year.

“A lot of people know climate change by another name,” Green said. “They know it by a storm, they know it by a flood, they know it by freeze. And they know it by saying this isn't normal, or this is weird, or this is different.”

Devin Wright, the research and policy manager for Sprout, says climate change impacts on agriculture must be addressed at the policy level, making the conversations around the Farm Bill all that more important.

“The Farm Bill is a behemoth,” Wright said. “There's a lot of energy around specifically trying to incorporate climate and climate change, or think about climate change, in the context of agriculture.”

Floodlight depends on a community of readers like you who are committed to supporting nonprofit investigative journalism. Donate to see more stories like this one.