EV factory plans still alive in Georgia, backers insist, but big hurdles remain

A proposed plant in Fort Valley, Ga., is moving ahead, a Florida businessman said, but electric vehicle factories in Oklahoma and Arkansas appear dead.

Republished by Georgia Public Broadcasting

The head of Imola Automotive USA — the startup that promised to create 45,000 electric vehicle jobs in struggling U.S. towns — acknowledged Tuesday that the company has been unable to secure land in two of the communities where it had proposed building manufacturing plants.

Still, he said, Imola hopes to break ground on a plant in Fort Valley, Georgia, within nine to 12 months.

During a press conference there on Tuesday, Imola CEO Rodney Henry said the company plans to build a 40-acre solar farm to help power the plant. Henry was joined by Fort Valley Mayor Jeffery Lundy, who said the project would include a 500,000-square-foot manufacturing plant along with retail development and housing for workers.

“We’re here to create jobs,” Henry told reporters. “We’re here to help the community.”

Said Lundy: “Imola is coming to Fort Valley.”

Company representatives said Imola has received zoning approvals in Fort Valley but still needs to secure financing and obtain final design approval.

In January 2024, Imola announced plans to build six EV plants in the United States. But more than 18 months later, the company has yet to break ground on a single site, Floodlight reported in a story published in August.

Jay Taylor, an attorney representing Imola, acknowledged in a Friday letter to Floodlight that “while the projects have most certainly experienced material delays, the plans and the commitment to see them to fruition remain in effect.”

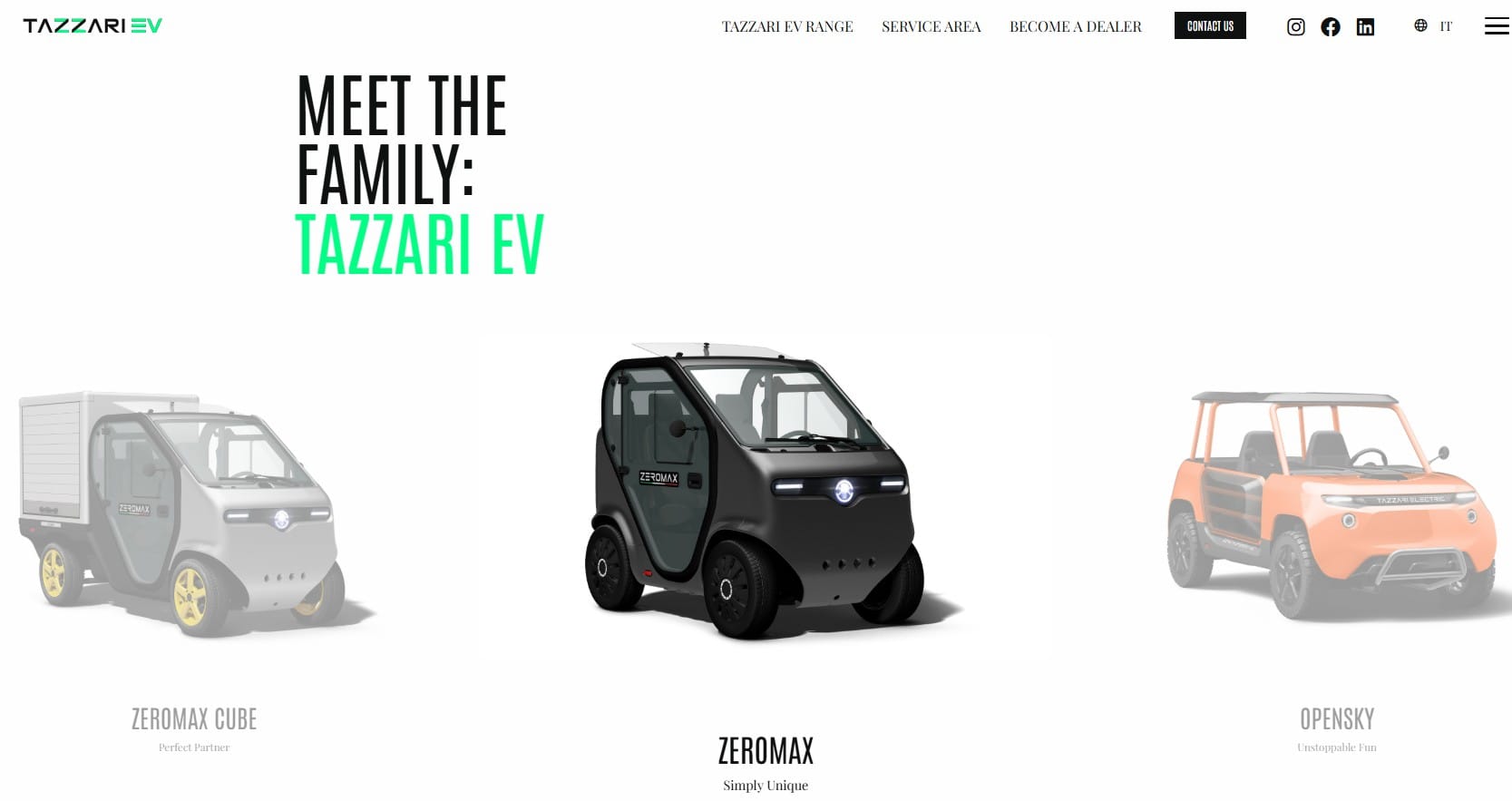

In early 2024, Imola Automotive USA and the Tazzari Group — an Italian firm best known for its electric two-seater micro cars — jointly announced plans for a partnership.

The EVs that Tazzari makes in Italy aren’t designed for highway driving. Top speed on the company’s Opensky Sport model is about 56 miles per hour, while maximum speed on the Opensky Limited is about 37 mph, according to the company’s webpage.

In response to a question from a reporter about the highway worthiness of the EVs, Henry responded the company plans to modify those cars so they can go up to 80 miles per hour.

Henry said Fort Valley is now the company’s top priority. He was less definitive about the future of proposals to build Imola plants in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and Langston, Oklahoma.

In Fort Valley, officials initially backed a plan for an EV facility expected to employ 7,500. But with no visible progress a year later, the company returned with a new pitch — a 99-year lighting contract. One council member called it a “bait and switch.”

Pierre Turner, Imola’s in-house counsel, said Tuesday that he has advised the company to drop the lighting project because “it wouldn’t be a good investment.”

Turner stressed that while Imola hopes to break ground on the EV factory in nine to 12 months, the company doesn’t know how tariffs and the global economy will affect its plans so “we’re not promising.”

Officials in Pine Bluff last year pledged land and infrastructure for a plant that was supposed to bring 8,000 jobs. But a year later, former Mayor Shirley Washington told Floodlight: “We never did get off the ground with that.”

Henry said on Tuesday that the town wasn’t able to provide the land needed to build a plant there.

In Langston — where over a third of residents live in poverty — an Imola representative cited problems acquiring land. The company had asked the city to transfer vacant property and issue bonds. City council member Magnus Scott told Floodlight that the deal was canceled before anything moved forward.

Henry said the company never canceled its plans in Langston. Property that Imola had hoped to build on in Langston became “unsecured,” Henry acknowledged. “So we didn’t have property to continue the project.”

Scott could not be reached for comment on Tuesday.

Henry, who lives in Florida, has no prior experience in auto manufacturing. His background includes work as a television executive producer and the founder of an athletic footwear brand.

In July, he declined to speak with Floodlight, instead issuing a brief statement saying the company’s timetable “has been modified due to matters outside of our control,” and that it remains “highly focused on bringing our goals into alignment.”

Floodlight submitted detailed questions to Henry and Taylor on Friday, requesting, among other things, details on the status of each proposed EV plant. Taylor responded on Monday night, writing, “Mr. Henry has agreed to provide responses at his earliest convenience.”

As of Tuesday evening, Henry had not responded.

Georgia Public Broadcasting reporter Grant Blankenship contributed to this story. Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powers stalling climate action.