This little-known ‘dark roof’ lobby may be making your city hotter

As cities heat up, reflective roofs could lower energy bills and help the climate. But dark roofing manufacturers are waging a quiet campaign to block new rules.

Published by The Guardian, Mother Jones, WWNO, Urban Milwaukee. Featured on KJZZ.

It began with a lobbyist’s pitch.

Tennessee Rep. Rusty Grills says a lobbyist proposed a simple idea: repeal the state’s requirement for reflective roofs on many commercial buildings.

In late March, Grills and his fellow lawmakers voted to eliminate the rule, scrapping a measure meant to save energy, lower temperatures and protect Tennesseans from extreme heat.

It was another win for a well-organized lobbying campaign led by manufacturers of dark roofing materials.

Industry representatives called the rollback in Tennessee a needed correction as more of the state moved into a hotter climate zone, expanding the reach of the state’s cool-roof rule. Critics, including a Democratic Tennessee lawmaker and a Washington, D.C., pastor, called it dangerous and “deceptive.”

“The new law will lead to higher energy costs and greater heat-related illnesses and deaths,” state Rep. Harold Love and the Rev. Jon Robinson wrote in a statement.

It will, they warned, make Nashville, Memphis, and other cities hotter — particularly in underserved Black and Latino communities, where many struggle to pay their utility bills. Similar lobbying has played out in Denver, Baltimore and at the national level.

Industry groups have questioned the decades-old science behind cool roofs, downplayed the benefits and warned of reduced choice and unintended consequences. “A one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t consider climate variation across different regions,” wrote Ellen Thorp, the executive director of the EPDM Roofing Association, which represents an industry built primarily on dark materials.

But the weight of the scientific evidence is clear: On hot days, light-colored roofs can stay more than 50 degrees cooler than dark ones, helping cut energy use, curb greenhouse gas emissions and reduce heat-related illnesses and deaths. One recent study found that reflective roofs could have saved the lives of more than 240 people who died in London’s 2018 heatwave.

At least eight states — and more than a dozen cities in other states — have adopted cool-roof requirements, according to the Smart Surfaces Coalition, a national group of public health and environmental groups that promote reflective roofs, trees and other solutions to make cities healthier.

Just months ago, industry representatives lobbied successfully against expanding cool roof recommendations in national energy efficiency codes — the standards that many cities and states use to set building regulations.

Thorp has said the goal is to emphasize “holistic” roofing solutions. Critics say it’s about protecting profits.

The stakes are high. As global temperatures rise and heat waves grow more deadly, the roofs over our heads have become battlefields in a consequential climate war.

It’s happening at a time when the Trump administration and Congress are derailing measures designed to make appliances and buildings more energy efficient. In March, for instance, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development delayed compliance deadlines for federally financed new homes to meet updated energy-efficiency standards.

Why roof color matters

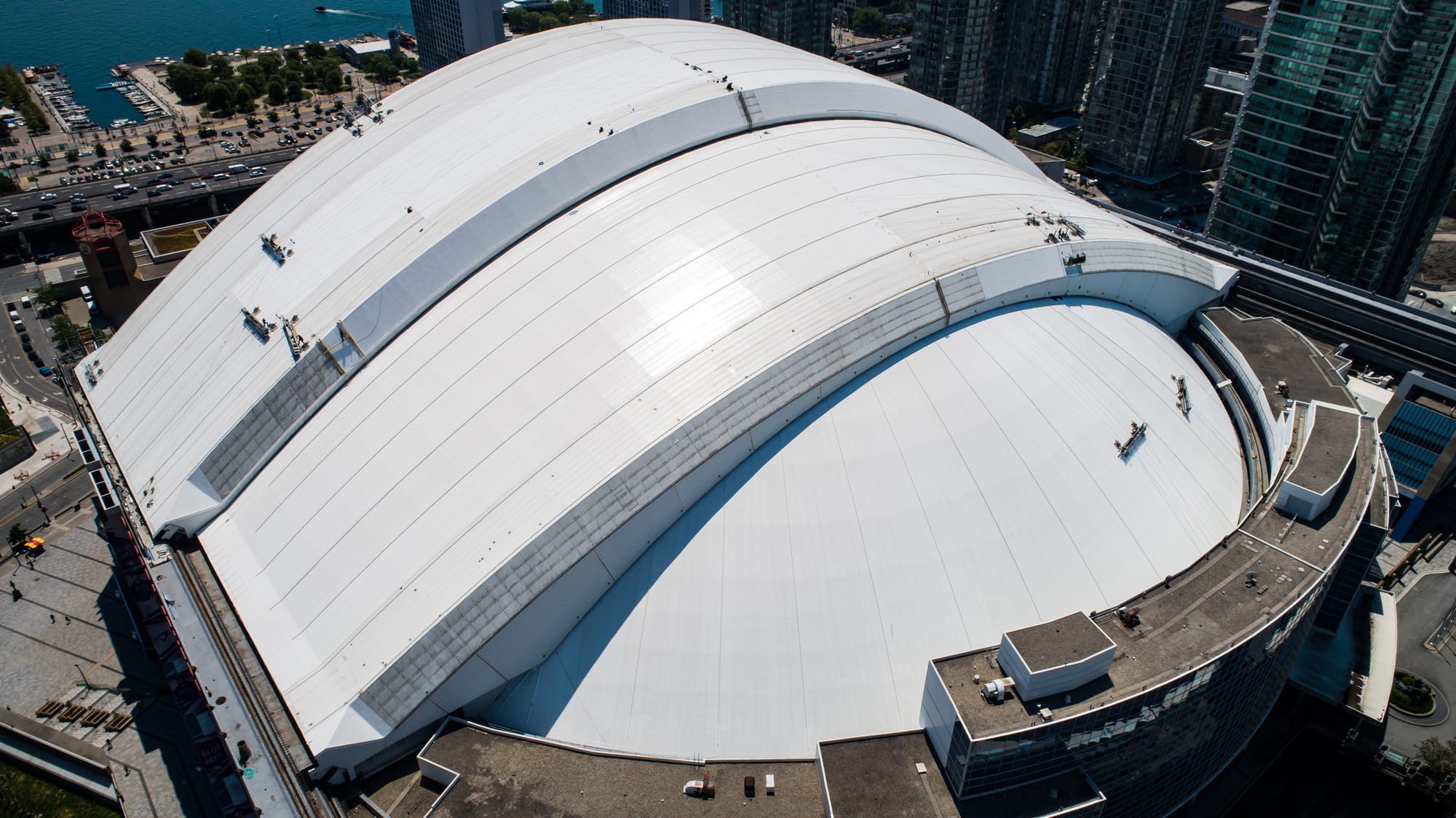

The principle is simple: Light-colored roofs reflect sunlight, so buildings stay cooler. Dark ones absorb heat, driving up temperatures inside buildings and in the surrounding air.

Roofs comprise up to one-fourth of the surface area of major U.S. cities, researchers say, so the color of roofs can make a big difference in urban areas.

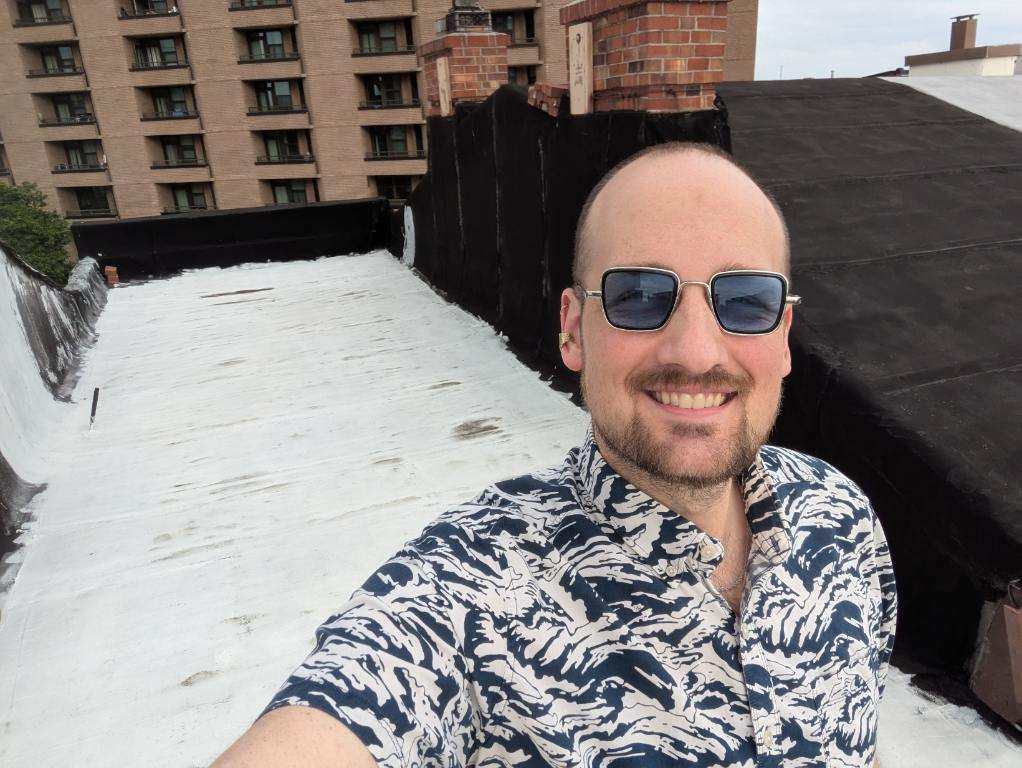

Just how hot can dark roofs get?

“You can physically burn your hands on these roofs,” said Bill Updike, who used to install solar panels and now works with the Smart Surfaces Coalition.

Study after study has confirmed the benefits of light-colored roofs. They save energy, lower air conditioning bills and reduce city temperatures. They help prevent heat-related illnesses. And they typically cost no more than dark roofs.

Retrofitting 80% of commercial roofs in the United States with cool roofs would cut the need for air conditioning, reducing carbon dioxide emissions by more than 6 million tons — equivalent to the annual emissions of 1.2 million cars, according to a 2009 study by scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

A later study by the same laboratory found that a cool roof on a home in central California saved 20% in annual energy costs.

In a three-story rowhouse in Baltimore, Owen Henry discovered what a difference a cool roof can make.

Living in a part of the city with few trees — and where summer temperatures often climb into the 90s — Henry wanted to trim his power bills and stay cooler while working in his third-floor office. So in 2023, he used $100 worth of white reflective roof paint to coat his roof.

Henry said he and his wife immediately saw the indoor temperature drop. They reduced their electricity use by 24%.

“For us, it made a huge difference,” he said.

Cool roofs, hot debate

Known for its durability, a black synthetic rubber known as EPDM once dominated commercial roofing. But in recent years it has been surpassed by TPO, a plastic single-ply material which is typically white and is better suited to meet the growing demand for reflective roofs.

Leading EPDM manufacturers — including Johns Manville, Carlisle SynTec and Elevate, a division of the Swiss multinational company Holcim — have fought against regulations that threaten to further diminish their market share.

Kurt Shickman, former executive director of the Global Cool Cities Alliance, said those companies have the money to hire top-notch lobbyists who know their way around hearing rooms — and who are on a first-name basis with decision makers.

“It's just been a real challenge to fight these battles,” he said of his group’s struggles with the EPDM industry. “...We’re dealing with huge entrenched interests here.”

The EPDM industry has paid for research that has asserted that the impact of cool-roof mandates is inconclusive, and that insulation plays a bigger role in saving energy than cool roofs.

They’ve also argued that cool roofs can contribute to condensation and mold. Target tested that theory on more than two dozen cool roofs installed on its stores and found no evidence of it.

In an emailed response to Floodlight’s questions, Thorp argued that many of the studies cited to support cool roof mandates leave out important factors, such as local climate variations, roof type, tree canopy and insulation thickness.

And she pointed to a recent study by Harvard researchers who concluded that white roofs and pavements may reduce precipitation, causing temperatures to unexpectedly increase in surrounding regions.

But Haider Taha, a leading expert on urban heat, identified multiple flaws in the Harvard study. In a review, he and a fellow researcher said it relied on unrealistic assumptions and oversimplified models, while ignoring key features of real-world cities.

As a result, Taha and his colleague wrote, “the study’s conclusions fail to provide actionable insights for urban cooling strategies or policymaking.”

A fight over cool roofs in Baltimore

When Baltimore debated a cool roof ordinance in 2022, Thorp’s group and the Asphalt Roofing Manufacturers Association (ARMA) lobbied hard against it, arguing that dark roofs are the most efficient choice in “northern climates like Baltimore.”

In cold climates, industry representatives note, cool roofs can lead to higher winter heating bills.

“Current research does not support the adoption of cool roofs as a measure that will achieve improved energy efficiency or reduced urban heat island,” Thorp wrote in a letter to one council member. “Increased insulation and improved urban tree canopy are the only measures that are broadly supported in the literature to achieve these goals.”

Multiple studies show otherwise. They’ve concluded that reflective roofs do save energy and cool cities by easing the “urban heat island effect” — the extra heat that gets trapped in many city neighborhoods because buildings and pavement soak up the sun.

Researchers have also found that even in most cold North American climates, the energy savings from cool roofs during warmer months outweighs any added heating costs in the winter.

Despite the opposition, Baltimore passed a cool-roof ordinance in 2023.

City Council member Mark Conway said he wasn’t surprised to see an industry trying to protect its business. But it was his job, he said, “to think about the greater good.”

Some who live in Baltimore’s lower-income neighborhoods can’t afford air conditioning, he said. And for them, Conway said, the reduced temperatures brought by cool roofs “can be life-changing.”

Opponents of cool roof requirements like Baltimore’s say they oversimplify a complex issue. In an email to Floodlight, ARMA Executive Vice President Reed Hitchcock said such rules aren’t a “magic bullet.” He encouraged regulators to consider a “whole building approach” — one that weighs insulation, shading and climate in addition to roof color to preserve design flexibility and consumer choice.

Henry, the Baltimore homeowner, said he thinks the city’s ordinance will help all residents.

“Everyone has to do a little bit in order for it to make a big difference,” he said. “And phooey to any manufacturer that’s going to try and stop us from maintaining our community and making it a pleasant place to live.”

Industry gets its way in Denver, Tennessee

Elsewhere, the industry’s lobbyists have notched victories.

In Denver, EPDM advocates waged a letter-writing campaign in 2015 that helped lead to the defeat of a cool-roof proposal. A narrower cool-roof ordinance, which applied only to new roofs on commercial buildings 25,000 square feet or larger, ultimately passed three years later, despite more opposition from the industry.

At the national level, Thorp’s group spoke out against a proposed code change that would have expanded standards for reflective roofs into cooler climates. The American Society of Heating, Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) — a professional organization that creates such standards — rejected the proposed change. The standards that ASHRAE sets are used as models for city and state regulations.

The current ASHRAE standard recommends reflective roofs on commercial buildings in U.S. climate zones 1, 2, and 3 — the country’s hottest regions. Those include most of the South, Hawaii, almost all of Texas, areas along the Mexican border and most of California.

But, Thorp said in a recent interview, “We've been able to stop all of those … mandates from creeping into climate zone 4 and 5.”

Another group headed by Thorp — the Coalition for Sustainable Roofing — worked with the lobbyist to propose the bill that eliminated Tennessee’s cool-roof requirement.

That rule once applied to commercial buildings in just 14 of the state’s 95 counties, but an update to climate maps in 2021 expanded the requirements to 20 more counties, including its most populous urban area — Nashville.

Grills, the Republican lawmaker who introduced the bill, was sold on the proposal to kill the regulation.

“At the end of the day,” he told Floodlight, “the consumer should be the one driving what they purchase, not regulatory agencies.”

At a state Senate committee meeting, Thorp called the bill “simply a fix, not quite administrative, but almost.”

The change was anything but administrative, the bill’s opponents say. It will put children, senior citizens and other vulnerable people at risk, said Love, the Nashville Democrat, and Robinson, the D.C. pastor who leads Metropolitan AME Church.

“That’s not a ‘fix’ worth supporting,” they wrote in their opinion piece.

‘Fed up with losing market share’

EPDM manufacturers also make light-colored roofing materials. Those include TPO and a white EPDM, which is typically more expensive — and much less commonly used — than its black counterpart.

Why, then, are manufacturers resisting cool-roof regulations?

Brian Whelan, a consultant who advises roofing manufacturing companies on environmentally sustainable practices and products, said the industry has invested heavily in building factories and production lines that produce dark roofing materials — and they’re reluctant to let that business go.

“They are kind of fed up with losing market share,” Whelan said.

EPDM manufacturers don’t publicly disclose how much of their business comes from dark versus reflective roofing, or the profit margins from each. But based on market intelligence, Whelan said, commercial roofing manufacturers likely make more money per square foot selling EPDM than TPO. Part of the reason: EPDM systems typically include high-margin accessories — like seam tapes and sealants — that aren’t necessary with TPO.

Greg Kats, CEO of the Smart Surfaces Coalition, dismisses many of the industry’s claims as disinformation.

“Those sorts of arguments are familiar to people who watch what went on in the smoking industry, the claims that there’s no correlation between smoking and cancer,” he said.

Even the name of one of Thorp’s lobbying groups — the Coalition for Sustainable Roofing — is misleading, Kats contends. A more accurate name, he said, would be “the Coalition to Prevent Cities from Protecting their Citizens, Cutting Energy Bills and Making Cities Resilient.”

Kats said the stakes are highest in low-income neighborhoods. He pointed to research conducted in Baltimore showing that poor communities are typically far hotter than affluent neighborhoods on a summer day, due to differences in tree and pavement cover.

As mercury rises, homeowner chooses a reflective roof

The public may be more receptive to cool roof policies than industry lobbyists suggest. Polls show many Americans support energy-efficiency measures.

Brian Spear, a homeowner in Tempe, Arizona, is among them. He’s lived in the Phoenix area since the 1980s, back when there were fewer than 30 days a year when the temperature reached 110 degrees. Last year, there were 70 of those days — the highest on record — followed only by 2023, when there were 55 days of 110 degrees plus.

These days, summer mornings start out scorching, he says, “and I feel like if you go outside between 10 and 4, it’s dangerous.”

Spear says he’ll soon replace the aging roof on an Airbnb home that he owns. After weighing the usual concerns — cost and aesthetics — he has chosen a roof that he believes will help rather than harm: a gray metal roof with a reflective coating.

“If someone told me you couldn’t put a dark roof on your house … I’d understand,” he said. “I’m all about it being for the common good.”

Even as mayors around the country seek to make their cities more livable, Kats believes the dark roofing industry will continue to resist.

Many of us have felt the sting of laying our hands on a dark car roof — or walking barefoot on black pavement — in the summer heat. Yet, Kats says, the dark roofing industry has pushed a message that boils down to this:

“You shouldn’t be trusting your experience, your senses.”

Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.